BY ALEX EBRAHIMI |

“A certain poet in outlandish clothes

Gathered a crowd in some Byzantine lane,

Talked of his country and its people, sang

To some stringed instrument none there had seen,

A wall behind his back, over his head

A latticed window.

His glance went up at times

As though one listened there,

and his voice sank

Or let its meaning mix into the strings.”

— W. B. Yeats

“Who is Phil Ochs?” might be answered by asking what seems like a very obscure question: What do Neil Young and Lady Gaga have in common? Two very different singers. Two very different generations. One seemingly very obscure question…if it wasn’t for the answer: Phil Ochs. The vastness of the gap bridged between the two very different generations is just one example of the vastness of Ochs. Another example is the vastness between the two very different Ochs songs they covered: Young going with the love song called “Changes,” Gaga calling for political changes with “The War Is Over.”

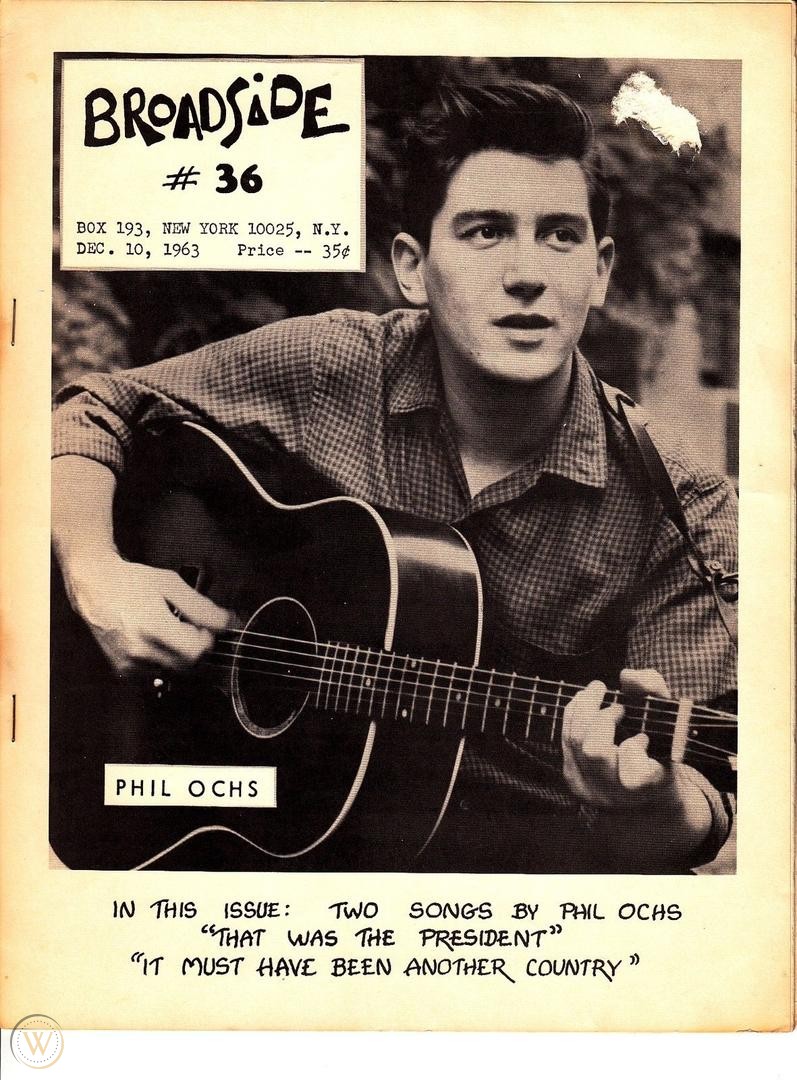

When the myth of Phil Ochs isn’t evaporating in the drought of silence around his name, it’s being drowned in the deluge of questions about his name. There’s the popular: “Wasn’t he that protest singer from the ’60s?” Or the tabloid: “Didn’t he have a falling out with Bob Dylan?” But the most popular, most tabloid: “Didn’t he kill himself?”

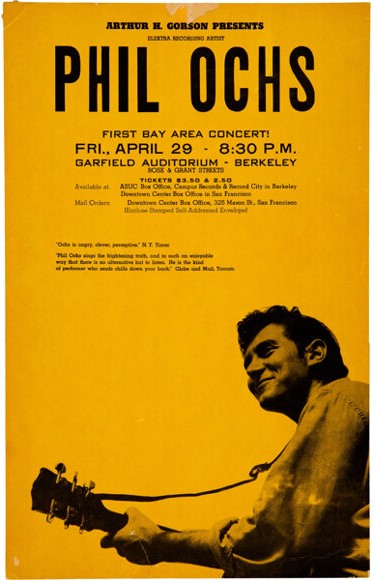

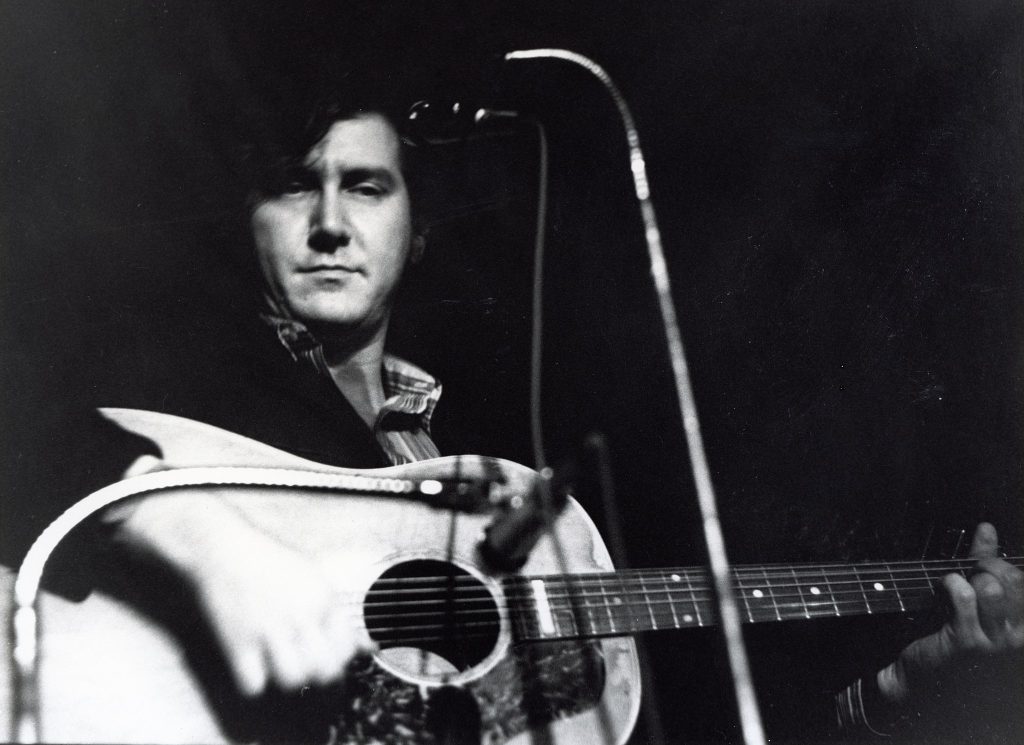

It’s hard to define Phil Ochs. As hard as trying to define America from the rise of the protest movement in the ’60s to the fall of Saigon in the ’70s. But in the middle of all the rising and falling, as Yeats penned, as Ochs lived: “a certain poet in outlandish clothes…talked of his country and its people.” So how does Ochs go from selling out Carnegie Hall as a troubadour who “talked of his country” in the ’60s to selling out Carnegie Hall as an Elvis impersonator in the ’70s?

“While I was out there in Los Angeles, it felt like I was back in New York because one by one, all the people I knew started to show up,” Ochs said in an interview with Folkways in 1968.

The Exodus of ’68 for California that Ochs talked about in that interview was as absurdly massive as the Gold Rush of 1849 and as massively absurd as “The Gold Rush” of Charlie Chaplin. When fortune was spelled in the shade of the Hollywood sign for the thousandth psychedelic rock band, Ochs found himself less in that lucrative shade than the shadow of a myth he later sang about in “Jim Dean of Indiana.”

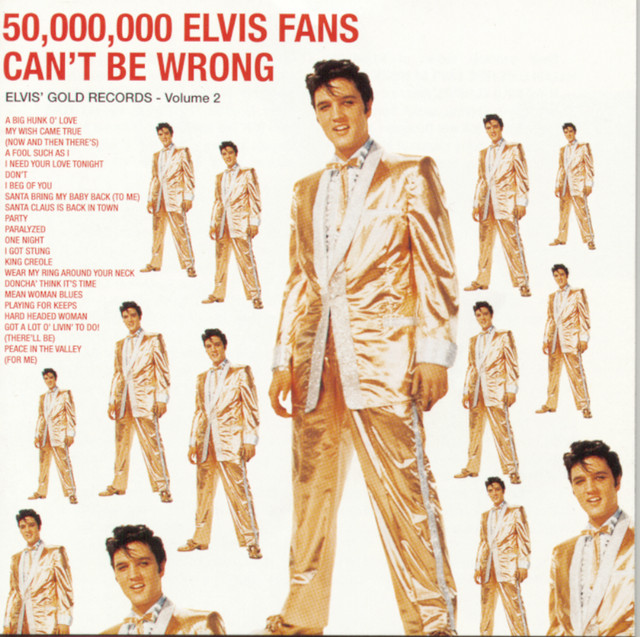

Both the Dean myth and the Ochs myth were grown out of the grain of the Midwest. Dean out of Indiana, Ochs out of Ohio. And California was a demise for both. Dean met his driving the spoils of stardom: a silver Porsche called “The Little Bastard.” Ochs met his searching for the spoils of the Gold Rush of ’68, only to return to New York donning a different kind of gold: Elvis’s lamé suit.

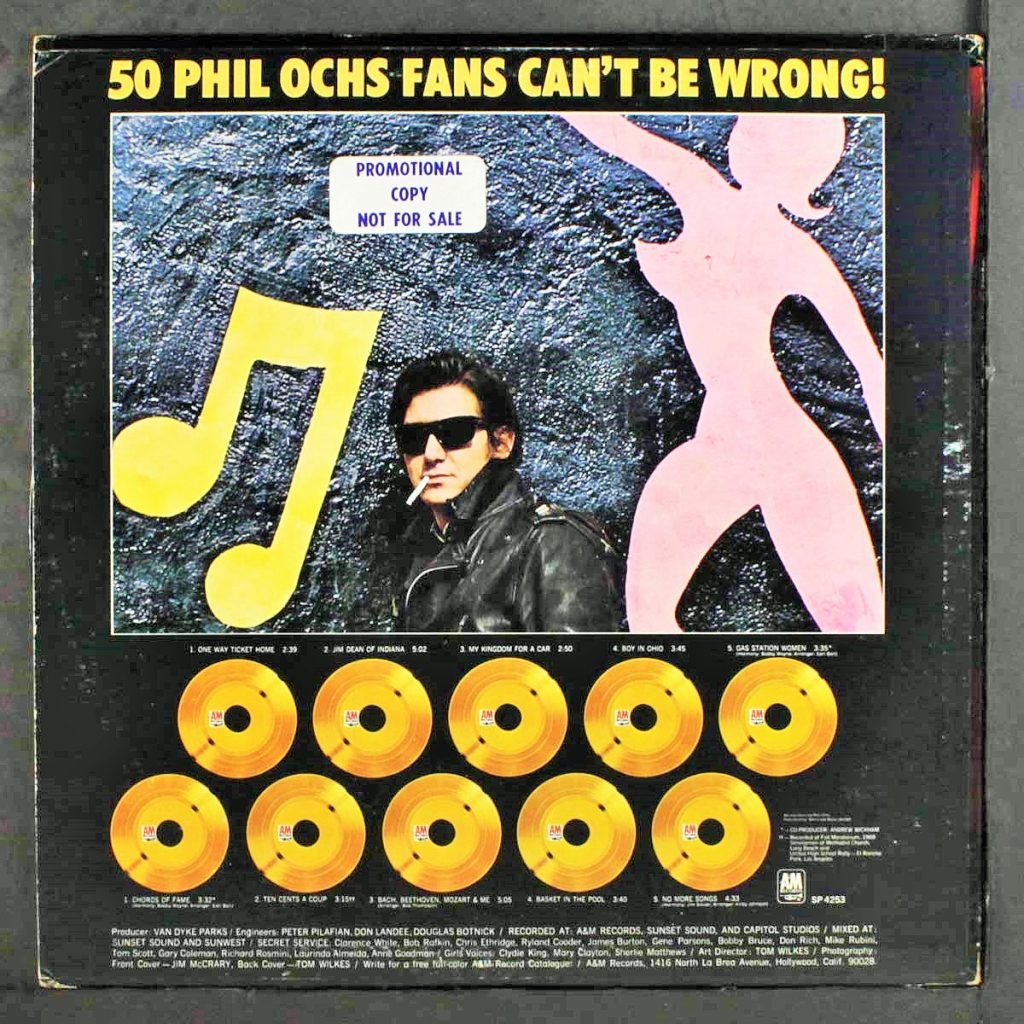

A decade earlier, when Elvis was the king of the charts, “50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong” was befitting the gold lamé. A decade later, when the gold lamé aged as well as petrified wood, “50 Phil Ochs Fans Can’t Be Wrong!” was befitting Ochs.

Ochs’s “Greatest Hits” wasn’t just the ultimate satire of the fact that he had none — despite Joan Baez’s cover of his song “There But For Fortune” being a chart contender, the gold lamé was a satire of the rise of the ’60s and the fall into the ’70s. Namely, Ochs’s theme song of the Exodus of ’68, “Chords of Fame,” about how dark the shade of the Hollywood sign really is — a song John Lennon personally considered an Ochs hit, and ultimately Ochs’s theme song of himself: “Jim Dean of Indiana.”

Ochs’s “Greatest Hits” wasn’t just the ultimate satire, it was his ultimate album. To quote the final song on the album, there would be “No More Songs” recorded in the studio. The only other album released in his lifetime was a live recording from a familiar stage, in front of a familiar audience, sold out by the walking satire of a sell-out: a very unfamiliar Ochs.

Fast forward to 1974, the year of Dylan and The Band getting back together, the year of The Beatles almost getting the band back together, and the hundred — and some change — year anniversary of the “Gunfight at the O. K. Corral.” So what better way to celebrate that milestone of Americana than the release of “Gunfight at Carnegie Hall”…in Canada.

“I got to talk to God and he said, ‘Well, all over here on Earth…what do you wanna do? You can go back and be anyone you want.’ So I thought, ‘Who do I wanna be?… . I decided the man who I wanted to be was…the man who was the king of pop, the king of music, the king of show business…Elvis Presley,'” Och said on the “Gunfight at Carnegie Hall.”

The answer to who was playing the role of Wyatt Earp in this gunfight was as clear as the answer to what was drowning out Ochs’s voice: the audience in front of him or the rock band behind him? Like the surge of the sea, the audience reacted to the stranger in the gold lamé suit taking the stage. One shout heard above the heckling surge, “Bring back Phil Ochs!” got the applause the stranger in the gold lamé suit wasn’t getting.

If the question “Who is Phil Ochs?” was being asked by his own fans when he was standing right there in the spotlight, how can it be answered today? Whitman might have contained multitudes; Ochs was drowning in them.

From the casual fans who’ve heard “Here’s to the State of Mississippi” to the devoted who’ve heard “Here’s to the State of Richard Nixon,” all 50 of them will give you 50 different answers. If one fan says Ochs is the singing journalist decrying the fate of the miners à la Aunt Molly Jackson, another will say Ochs is the poet arranging music for ballads like “The Highwayman” à la Alfred Noyes. If one fan says he’s the troubadour with songs like “Crucifixion” à la Kennedy’s assassination, another will say he’s the star donning the gold lamé suit à la Elvis Presley.

From Neil Young to Lady Gaga, all “50 Ochs Fans Can’t Be Wrong.” But even in a world where “50,000,000 Ochs Fans Can’t Be Wrong,” there is one wrong answer to “Who is Phil Ochs?”: John Train.

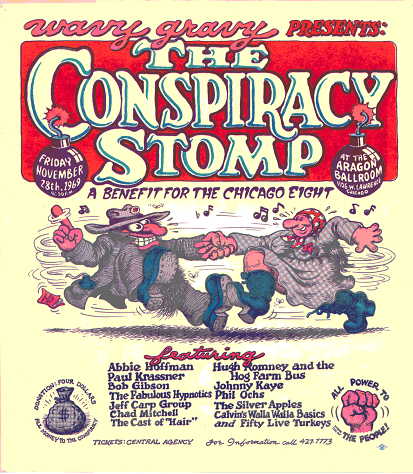

It’s too easy to write him off with that answer. As easy as calling petrified wood stone. When the ’60s fell into the ’70s, Ochs fell into an alter ego called John Train. But whether it started psychologically in Chicago at the ’68 Democratic Convention or physically in Africa in the ’70s when he was choked by two robbers on a beach, why romanticize the fall of Ochs any further? The consensus is well-lubricated. To the point where that spittle of sensationalism is getting in people’s eyes.

“I may not look like much, but I owned the world

And I gave it all away.

Now I’m an actor on the street

And I do it for no pay.”

— Ochs’s unreleased song from the 1975 “Street Actor”

What’s looked to most eyes like a white flag in his hand in ’75 — a year before his suicide —wasn’t a white flag at all and it wasn’t a bar tab and it wasn’t a prescription order…but the pages of an unreleased album called “Duel in the Sun.” That booze-complected shadow of himself, Train, didn’t completely kill him, as the consensus goes. And the only way to completely kill that narrative is Ochs’s lost album. The devoted and the casual would agree that Ochs was as pivotal to this country as Dylan. Who wouldn’t agree that, if Dylan had a lost album, it wouldn’t be lost for very long.

“My will is easy to decide,

For there is nothing to divide

My kin don’t need to fuss and moan —

‘Moss does not cling to a rolling stone’

My body?

Ah! If I could choose

I would want to ashes it reduce,

And let the merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers grow

Perhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life

And bloom again

This is my last and final will. —

Good luck to all of you,”

— Joe Hill

Who is Phil Ochs? In New York, he was the singing journalist who tried to be a poet. In California, he was the troubadour who tried to be a star. In the end, he was 35. One year shy of Joe Hill. One unreleased album shy of a comeback.

“It’s the life of a rebel that he chose to live,” to quote his song “Joe Hill” about the fellow troubadour’s rise and fall. It’s the stuff that myths are made of, to misquote the bard. So brush up your Phil Ochs, to answer the question yourself.

The Village Trip Festival is a good place to start… .

Shows like The Village Trip’s are what it takes to keep the songs alive, if this country’s more than 40 years late at keeping the singer alive. But don’t expect any eulogies. It’s too hard to eulogize a man who never died. As hard as killing off Joe Hill.

“The Village and Phil Ochs: Composers Interpret Phil Ochs,” Sun., Sept. 18, at Drom, 85 Avenue A, 6 p.m. to 10 p.m., tickets $20 to $30. Featured on the program are composers William Anderson, Lynn Bechtold, Frank Brickle, David Claman, Dan Cooper, Jennifer DeVore, Melanie Mitrano and Gene Pritsker, as they take inspiration from Ochs’s music and his milieu. The music is performed by Melanie Mitrano, voice; Bill Anderson and Gene Pritsker, guitars; Joan Forsyth and Mari Asakawa, piano and Zentripetal; Lynn Bechtold violin; and Jen DeVore, cello. For tickets, click here.

“Chords of Fame: A Salute to Phil Ochs,” Wed., Sept. 21, at The Bitter End, 147 Bleecker St., 6:15 p.m. to 8:45 p.m., tickets $20 to $25. With musicians Reggie Harris, Magpie (Terry Leonino and Greg Artzner), Our Band (Sasha Papernik and Justin Poindexter) and David Amram. The evening, which will be emceed by Danny Goldberg, a distinguished author and journalist who has long revered the music of this timeless talent, will begin with film footage of Ochs. For tickets, click here.

Be First to Comment