BY PAUL DeRIENZO | Long before coronavirus threatened New Yorkers, there were waves of disease epidemics that regularly sliced through the city. Little was known about what caused these pestilences until well after the Civil War.

In 1850, the average age of death of New Yorkers was less than 21 years old. Child mortality was about 40 percent at age 5. That’s why families were large, about six children per woman. Epidemics in the 19th century were caused by diseases that were mostly conquered by the 20th century. Smallpox ravished the city nine times in the century, while cholera swept across New York on five occasions. Yellow fever, scarlet fever, typhus, diphtheria, meningitis and influenza hit the city again and again.

Cholera is a bacterial disease that originates in shellfish and other sea creatures living offshore until undercooked seafood brought it into the human population. The bacteria would then be further spread through sewage and feces to the entire population in a stricken area.

The first recorded outbreaks apparently happened in India near the city of Calcutta, giving the disease the name Asiatic cholera, to differentiate from other milder forms of the disease, such as English cholera, which had swept through England earlier in the century.

The disease migrated to England via trade roots from Russia, from which it arrived in Eastern Europe. Cholera struck England, particularly the market town of York, in the spring of 1832.

The disease took on a political dimension, not too different from what we see in the United States today. In England, merchants knew they would be hit by a quarantine that would disrupt business, so city fathers wanted to play down the disease from the start.

There were opposing theories about the source of the sickness that were both wrong. The first was that there’s an innate tendency to the illness among the poor, who could spread it to others. The second was called the miasma theory — that the illness came from the stench of garbage and rotting filth. The miasma theory was a little more helpful because it implied the best course of action was to clean the streets, and fix backed-up sewer drains.

Cholera, in fact, is spread by untreated sewage, which flowed into the river and polluted wells. No amount of cleaning could entirely fix the problem. Wealthier households had filtered water, but the technology was far from perfect.

Doctors worked for free treating thousands of people; public hospitals were thrown up quickly and funded by emergency tax levies.

The treatments were generally useless. Cholera kills when the bacteria gets into the small intestine, inducing diarrhea, which can kill within hours through dehydration. Occasionally, doctors would stumble onto the cure — lots of liquids and salt to rehydrate the patient — but no pattern was detected.

The rich people tended to argue over the cost and the usefulness of the hated quarantines that interfered with business. Newspapers refused to even tell people cholera was in their towns, so as to forestall panics that might hurt business.

Meanwhile, the poor turned to a fear and hatred of the very doctors treating them. The most common conspiracy theory was the belief that doctors were killing people and using the corpses for dissection by medical students.

Across the Atlantic, New Yorkers were not ignorant of these events in their namesake city. Although a deeply Christian society, the United States had no established clergy as in England, relying instead on civil authorities to a greater extent for instructions.

Even so, Americans believed God smiled on them to a greater degree because of their pious beliefs and doubted that a similar fate as Europe awaited them. Americans prided themselves in being a rural people, surrounded by cleaner air and water. Boston and Philadelphia seemed much cleaner than London — but New York stood out as a problem.

New York was perceived as a dirty, crowded town full of sinners, violent and vicious enough to provoke the wrath of the divine. The city was filthy and the only garbage collection were the pigs that ate the trash tossed into the streets. People lived in close quarters with animals and the Common Council was generally indifferent to sanitation.

Tammany, the local political machine, was more interested in graft, so money appropriated for street cleaning disappeared into the pockets of political bosses.

The launch of the municipal water system had been delayed. Water had come from wells throughout the city. One of the most famous wells, the Tea Well, was in Chatham Square near Bayard St. The water had been considered sweet and perfect for a good cup of tea since the 18th century.

Running water was unheard of in New York until the Croton Aqueduct was completed in the 1840s. Travelers wrote of the endemic stomach illnesses that seemed to come from the city’s water and the swarming flies that overtook kitchens and sickened diners.

The authority of the city’s Board of Health was limited or nonexistent. The board grew out of 18th-century temporary health committees that became permanent in 1822 following a yellow fever outbreak. Merchants openly derided any talk of quarantine and the health board was seen as “more afraid of merchants than lying,” according to contemporary diarists.

As reports came from Europe of the spreading plague, the city’s mayor, Walter Bowne, declared a quarantine on ships from Europe and Asia. A few days later, word reached the city of a cholera case in Montreal — the disease had made landfall.

Cholera would follow the Hudson River south, reaching New York City by July 1832, killing 1,800 that month alone.

Thousands crowded the roads trying to leave the city for what they believed was the safety of the countryside. The disease hit hardest in the poorest neighborhoods, particularly the slum known as Five Points — not far from City Hall — where African-Americans and immigrant Irish Catholics lived crowded together.

Many of the rich believed the poor were the problem and the sooner they died the better.

“Those sickened must be cured or die off, & being chiefly of the very scum of the city, the quicker [their] dispatch the sooner the malady will cease,” wrote John Pintard, a founder of the New-York Historical Society.

According to historian Kenneth T. Jackson, “If you got cholera, it was your own fault.”

That August another 1,200 died before deaths fell to 451 in September. By the fall, cholera had run its course for the time being. Total cholera deaths for 1832 in New York City came in at more than 3,500. The disease was on hiatus, but not gone.

Today scientists believe the cholera epidemic continued unabated in Asia, even as it seemed to disappear in North America. As the 1840s wore on, the disease followed the Mississippi River system, infecting St. Louis.

New York City soldiered on with improvements in the quality of city dwellers’ lives. The Croton Aqueduct was completed in 1842 and the backyard wells that contributed to the 1832 outbreak were phased out. In 1849, the municipal government banished more than 20,000 pigs from the streets of Manhattan.

Still, fear gripped the city when in November 1848 a shipload of French and German passengers arrived with some suffering with cholera. Seven were buried at sea. Others were put in hospitals, from where the disease spread throughout Staten Island. It made the jump to Manhattan by May 1849, gradually spreading across the city.

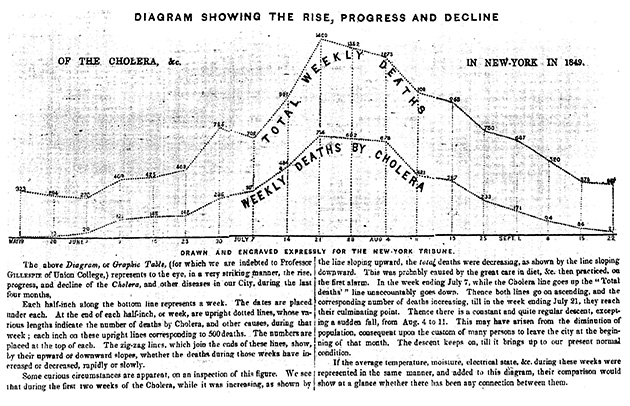

Deaths peaked at more than 2,600 that July, followed by 1,451 in August.

The year 1848 was one of upheaval in Europe. Revolutions and wars raged across the continent, while a famine devastated Ireland, sparking a mass migration to the United States. The center of the outbreak was again the slum of Five Points, as it had been in 1832.

But the rich were not immune. In 1849 a wealthy merchant named Benjamin Whitlock, his young wife Maria and his mother Mary were living at 9 Rutgers St., a few doors down from Maria’s family, the Hawleys, at 21 Rutgers St., half a block from East Broadway.

An 1832 sales notice describes the Hawley residence: a three-story brick house, on a lot 25 feet wide and 104 feet deep, with an alleyway connecting to Henry St., “built…in the best manner, and in the modern style, with elegant marble mantles…and a large brick cistern in the yard.”

Cisterns are circular structures built to catch rainwater and a sign of how difficult it was to get fresh water in New York before the Croton Aqueduct water reached the city.

Benjamin Whitlock and Maria Louisa had a daughter, Sarah Louisa Hawley Whitlock, born Nov. 16, 1847, almost one year to the day after her parents’ marriage. It was less than two years later, on Aug. 20, 1849, that Maria Louisa Hawley would be dead at the height of the cholera epidemic.

Maria Louisa’s death certificate marks her as 23 at the time of death; the cause of death is left blank. Death from cholera was widely blamed on the victims of the disease, blamed for their sinfulness. So when a rich New Yorker died, it was common to leave the cause of death unsaid. Whether Maria Louisa died that summer of cholera in the middle of the worst epidemic in New York City history will never be known.

In the later half of the 19th century, both England and the U.S. made huge strides in public health. Water, sewer systems and garbage collection were greatly improved over time. The result was a steady increase in lifespan and the seeming conquest of infectious disease.

But as history repeats itself with the current plague, can it be said that we really learned the lesson of history? When public health is subordinated to fear, ignorance and avarice, we give disease free reign to walk among us.

Allison – I found an ancestor who died from cholera in August 1849 listed in the 1850 Federal Census Mortality schedule. He died in New York but he was listed in the Newark census, which is where I think he lived at the time.

Death records in NYC do not exist it appears before 1855 in Manhattan. Wondering if there exists, at very least, a list of the names of the dead from cholera in 1849. I believe my 4th Great-Grandfather may have been one that succumbed to it in June 1849, but cannot find a death cert anywhere.

Occasional death certificates exist oftentimes searchable on the Internet. Wealthy individuals avoided putting cholera as cause of death because it was considered a poor person’s disease

Many were very poor and not included in any census.

Great historical recounting, not only of the history of a pandemic, but of the history of How it affected our city.

New York City is often defined by how its residents respond to disasters.

Just realizing how fortunate we are that our great-great-grands survived these devastating waves of disease long enough for us to get here. Eerie to read these echoes of prioritizing business over life and proneness to conspiracy theory, xenophobia, and hatred of New York City. Such a readable article!