BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Who exactly — if anyone — is in charge of enforcement for the city’s new Open Restaurants program?

That was the overriding question at an East Side town hall meeting Tuesday evening on the city’s outdoor dining initiative that was created in response to COVID. The answer — or lack thereof — was not what community board members and locals had hoped to hear.

The town hall was co-hosted by Community Boards 3 and 6, which together cover the East Side from the Brooklyn Bridge up to E. 60th St.

Representatives from a potpourri of city agencies — such as the Mayor’s Office, the Department of Transportation and the Fire Department — spoke at the virtual Zoom meeting. But when certain specific questions were asked, such as who oversees complaints about noise and music stemming from outdoor dining and who is enforcing regulations on the outdoor dining structures, there was either silence or confusing answers by the reps.

The meeting was moderated by Paul Rangel, chairperson of the C.B. 3 Transportation, Public Safety and Environment Committee, with help from Michelle Kuppersmith, the new chairperson of the board’s State Liquor Authority and Department of Consumer Affairs Licensing Committee.

At the end of the town hall, Rangel summed things up by saying, “It seems it’s too many cooks in the kitchen — and we can’t figure it out. Jurisdiction and enforcement were clearly the main issues at the meeting.”

“Everybody’s very confused about who’s in charge,” echoed Kuppersmith. “I think that’s the overarching thing here. It seems like there’s a real patchwork of agencies here. People are very confused — as am I.”

Susan Stetzer, the C.B. 3 district manager, said, “I think one of the biggest problems is lack of enforcement. A lot of people go out and look at things [during inspections] — but we need real enforcement, which does not mean fines but that the problem is fixed.”

Earlier in the meeting, Stetzer said, “Residents feel like they’re complaining but [the city is] not responding.”

However, Brady Hamed, chief of staff of the Mayor’s Office of Operations, responded, “Rest assured that we are watching those 311 complaints closely and agencies are responding to the vast majority of them.”

Kicking things off, Councilmember Carlina Rivera said the Open Restaurants and Open Streets: Restaurants programs are vitally important to not only local businesses but also the community.

She said that, despite the vaccine, she believes the COVID pandemic will still be with us in the coming summer.

“We need to keep our community alive as much as possible,” she said. “Many of us feel safer [on the streets] with our local businesses open.”

At the same time, Rivera acknowledged her office has received complaints about the outdoor dining structures and related issues.

“I take them very seriously,” she said of the complaints of violations.

The councilmember pledged that community members would have a seat at the table if the Open Restaurants program is renewed after one year, which the mayor and City Council support doing.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer noted that, in one way or another, a total of 25 different city agencies are involved with the outdoor dining program. As a result, she suggested designating an official to oversee the program.

“A ‘public realm czar,'” she offered, though adding, “there must be a better name than that.”

Ed Pincar, the D.O.T. Manhattan borough commissioner, said there are 450 inspectors who, on a daily basis, are monitoring how the Outdoor Restaurants program is operating. These inspectors are not all from one agency, though, but from various agencies.

He noted that about 11,000 bars and restaurants citywide are participating in the program, with about 5,000 in Manhattan alone.

“When we set it up, it was down and dirty,” he conceded of the program, meaning it was slapped together quickly.

“Since July 1, we’ve conducted more than 11,000 inspections [for things like] distance from hydrant, sidewalk clearance,” he said. He added that the inspectors try to revisit the problem site the next day to verify that the issue has been addressed.

Andrew Kunkes, also of the Mayor’s Office, said, typically, a verbal warning is given for an Open Restaurants violation, with someone then returning to check the outcome.

Although D.O.T. created the Open Restaurants program, Pincar said it’s not “not necessarily” the agency to respond to complaints of people not wearing face masks or places operating beyond permitted hours.

Fire Chief Jack Spillane of the Fourth Battalion, based on Pitt St. on the Lower East Side, said not all restaurants are abiding by the rules.

“You have certain bad actors,” he stated. “You do your best.”

Two other fire chiefs spoke about dealing with “L.P.G.,” or propane gas, which is being used to heat the outdoor dining areas. One of them said that, if firefighters feel a situation with propane tanks is hazardous, they will remain at the scene until the problem is safely resolved.

One of the chiefs noted that often it’s the Fire Department that is first noticing problems with specific restaurants.

Local residents submitted questions to the community boards for the officials, and Rangel and Kuppersmith curated them and picked which ones to ask. C.B. 3 members also asked their own questions.

In response to a question that noted, “the rules keep changing,” regarding outdoor structures, Hamed agreed, saying, “This is a big issue for us.” He said the rule changes are often coming from Albany.

C.B. 3 member David Crane mentioned a problem spot in the East Village — Avenue B between Second and Third Sts. — where the outdoor dining is sprawling way too far into the roadbed.

“There is a boozy brunch place that puts their tables out to the yellow line,” he said. “Fire trucks can’t get by. It’s taken six months and it hasn’t been addressed. I would imagine if they are being fined, it would end.”

Pincar and Hamed both said they know that’s a bad spot — Hamed because he lives in the neighborhood. However, Pincar announced that D.O.T. will “pause” the Open Street on Avenue B between Second and Fourth Sts. for the rest of the winter, in hopes of fixing the problems there and then relaunching it in the spring.

Kuppersmith chimed in that a goal should be “to find a way to remove cars from the streets as much as possible” so people have more walking space.

Pincar responded that, in fact, the agency plans to create some permanent carless Open Streets in Manhattan after having recently done this with 34th St. in Queens.

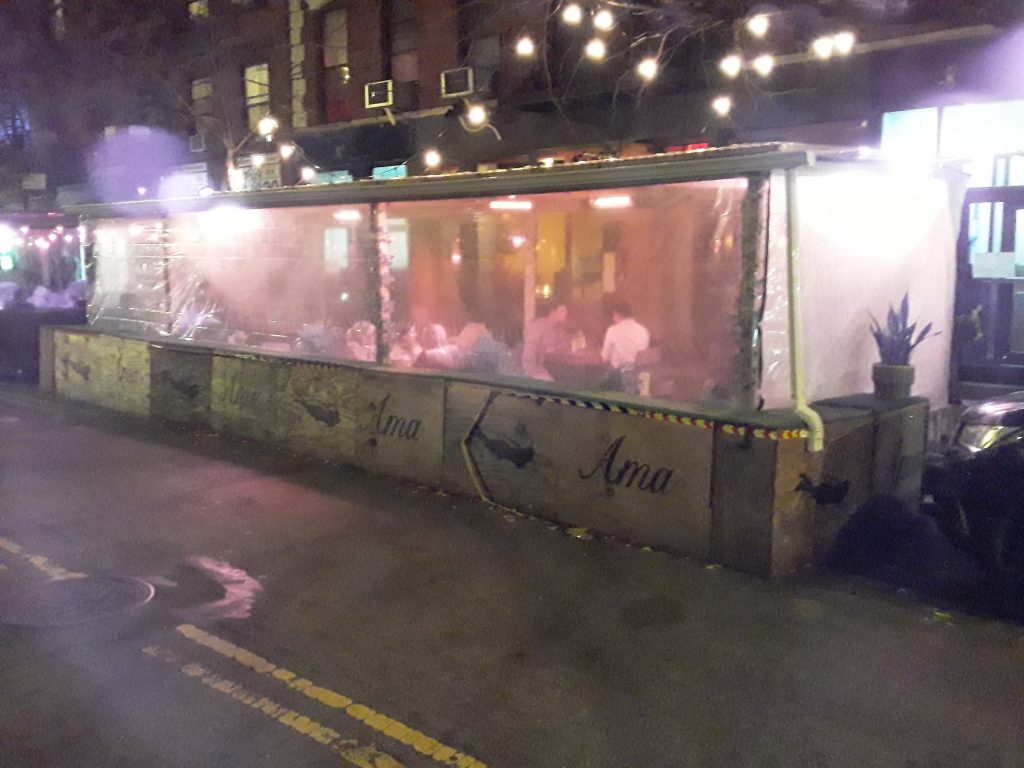

At one point, the officials were asked about something so many are no doubt wondering about: Namely, how can so many of the outdoor dining structures be legal when they appear to be closed off on nearly all sides? Enclosing the structures means they are not getting ventilation, which is needed to help prevent the spread of COVID.

Hamed, from the Mayor’s Office, explained that “one long side and one short side” of the structures need to be open for them to be considered legal. He said all of the 450 Open Restaurants inspectors have been trained to check for this.

Another D.O.T. spokesperson, Kyle Gorman, then claimed that the overhead part of the outdoor structures actually falls under the purview of the Department of Buildings. But Stetzer interrupted to say that was simply not accurate.

“It’s not a D.O.B. issue,” she objected.

“I’m going to refer back to the Mayor’s Office,” the spokesperson deflected.

Joseph Akryod, a D.O.B. official, sounded confident in his grasp of the rules.

“If you enclose outdoor dining, it has to be treated like indoor dining, 25 percent [capacity],” he said. “But indoor dining is not currently allowed, so [the outdoor structure] must be 50 percent open.”

As if there wasn’t enough confusion already, one agency rep referred to the outdoor structures as “yurts” — as in, the portable round tents covered in animals skins favored by Mongolian nomads.

Another question asked if Open Streets could accommodate other uses beyond just bars and restaurants.

“We definitely are interesting in engaging with those [other] types of businesses to layer them onto open streets,” Gorman said.

Gorman said that Open Streets might be designated spots for the new Open Culture program for outdoor music and performances.

One local resident wondered if music simply could be “eliminated” from Open Restaurants.

“I believe that people will come to eat without music,” the question read. “It only causes people to talk more loudly.”

Ironically, though, the suggestion to eliminate music was greeted by the proverbial deafening silence. Not a single agency rep volunteered a response.

Eventually, Hamed said, “I don’t have a strong answer [on that],” adding he would “go back and try to find out more on it.”

Apparently, Rivera was no longer on the Zoom call. But Jeremy Unger, her communications director, interjected, “That no one could answer the question on noise was very concerning.”

Another person who submitted a question asked what is being done about those “yurts” left behind on the street when businesses permanently close. A D.O.T. spokesperson said to call 311 and either the city will contact the owner to dismantle the structures or the Department of Sanitation will remove them.

Be First to Comment