BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Alarm over climate change is the story of the day.

Teenage activist Greta Thunberg — whose fiery speech at the recent United Nations Climate Action Summit made headlines — is an environmental icon.

Extinction Rebellion has been staging actions around the globe. At Lower Manhattan’s “Charging Bull,” the group’s members held a die-in and doused the capitalist symbol with fake blood; in London, a partially blind activist glued himself to the top of a jet plane.

And the leading Democratic presidential candidates have all declared that addressing global warming is one of their top issues — if not their most important one.

Yet it wasn’t until the late 1980s that the U.S. media started warming up to the issue of global warming. And it was only a few years before that, in 1977, that President Jimmy Carter first warned of a looming energy shortage, urging it was time to look to “permanent renewable energy sources, like solar power.”

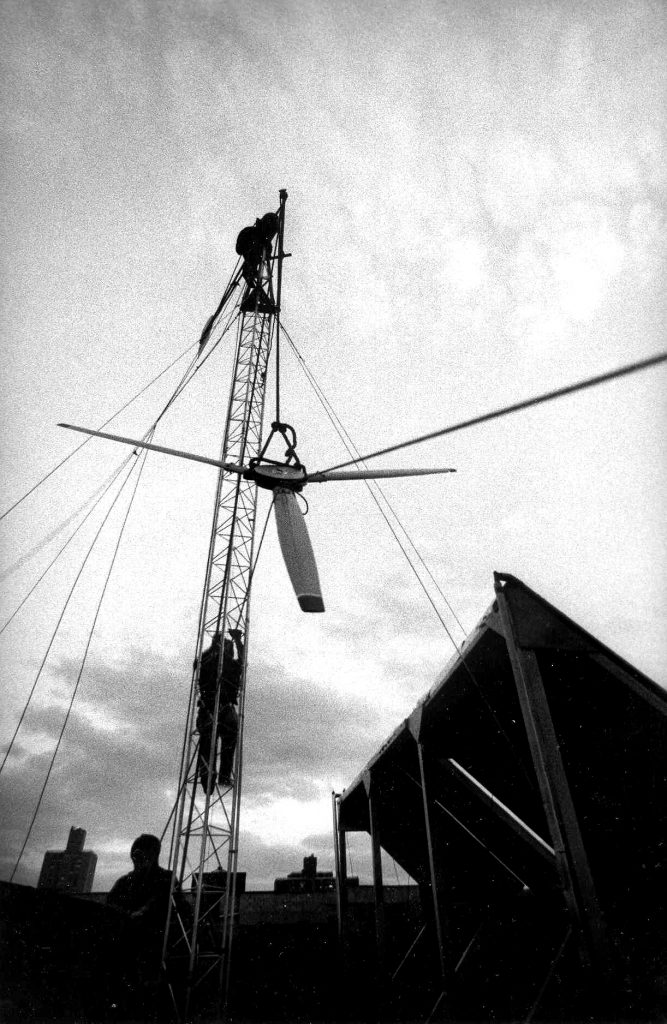

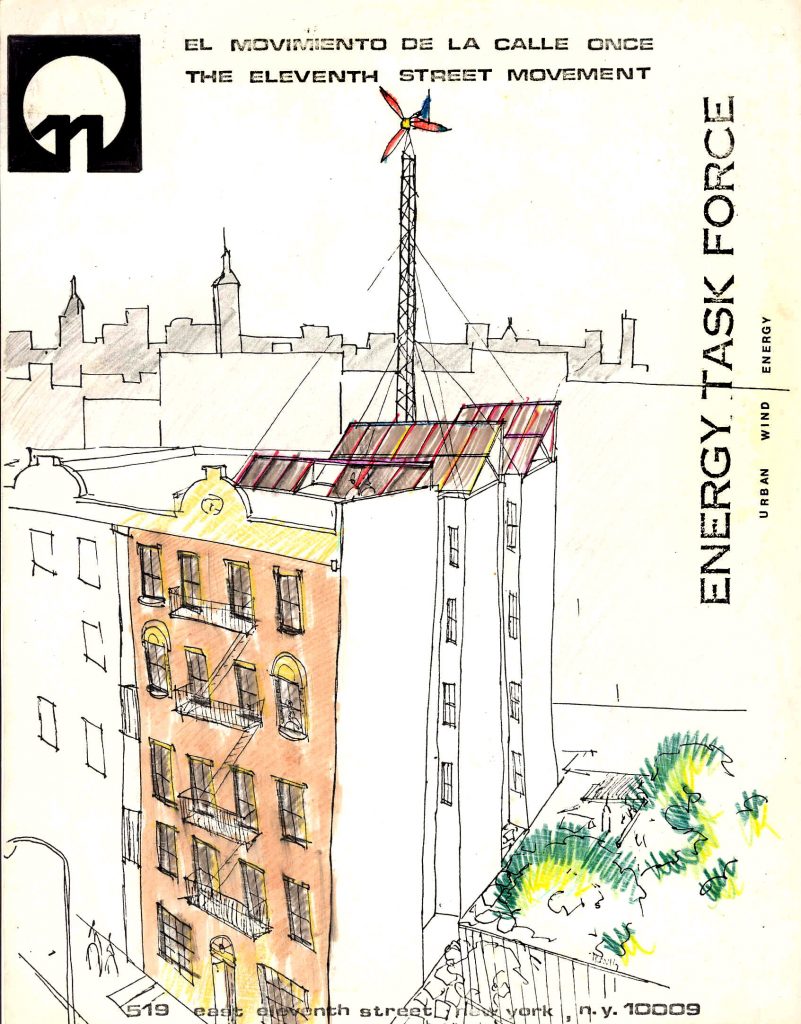

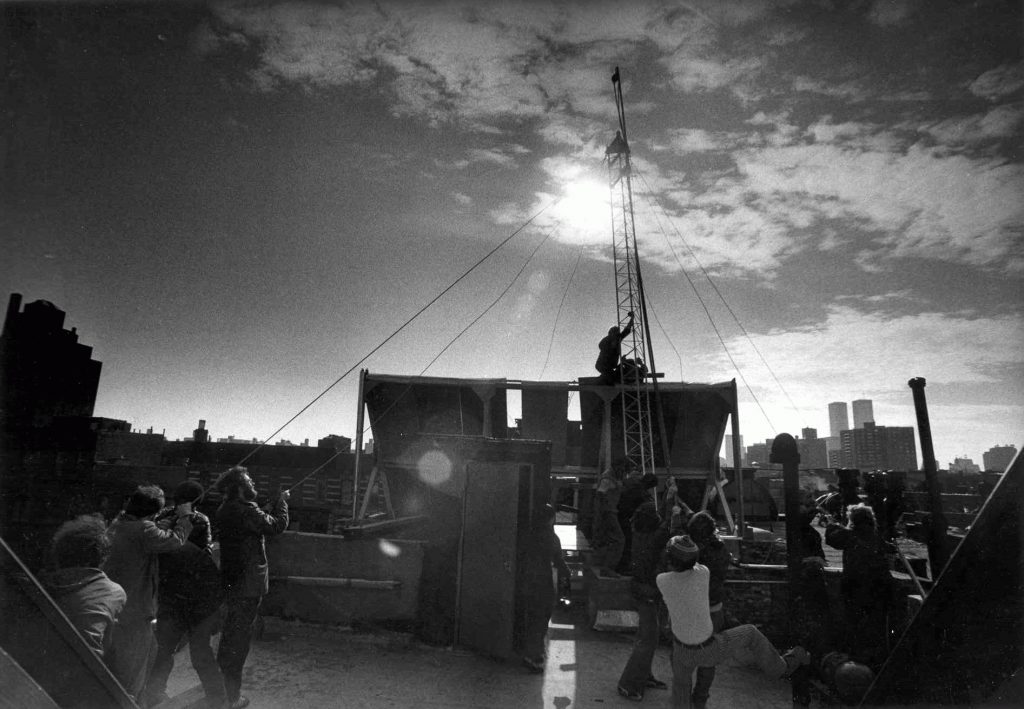

Meanwhile, on the Lower East Side — as the East Village was then still known — a group of environmental pioneers was doing just that. Their project began as a gut-rehab of an abandoned 1910 tenement at 519 E. 11th St., between Avenues A and B. By the time the work concluded, the building also sported two cutting-edge forms of renewable energy on its rooftop — a wind generator, plus solar panels.

Solar power was then still in its infancy for use for residential buildings. The Jacobs-brand wind generator, purchased for about $5,000, had previously been used on a Midwestern farm to pump water up from underground.

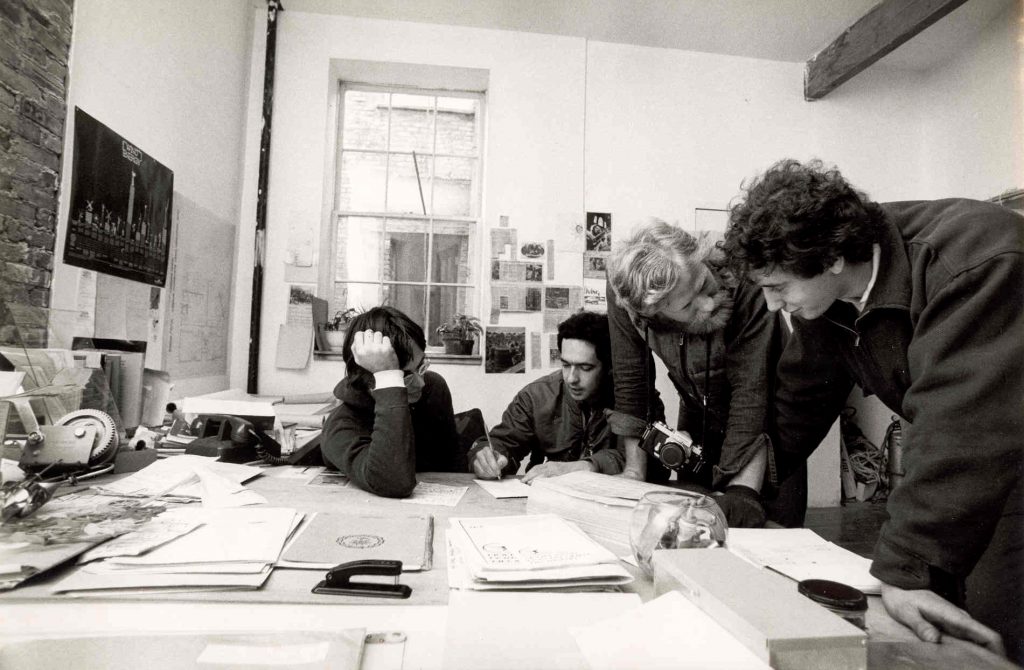

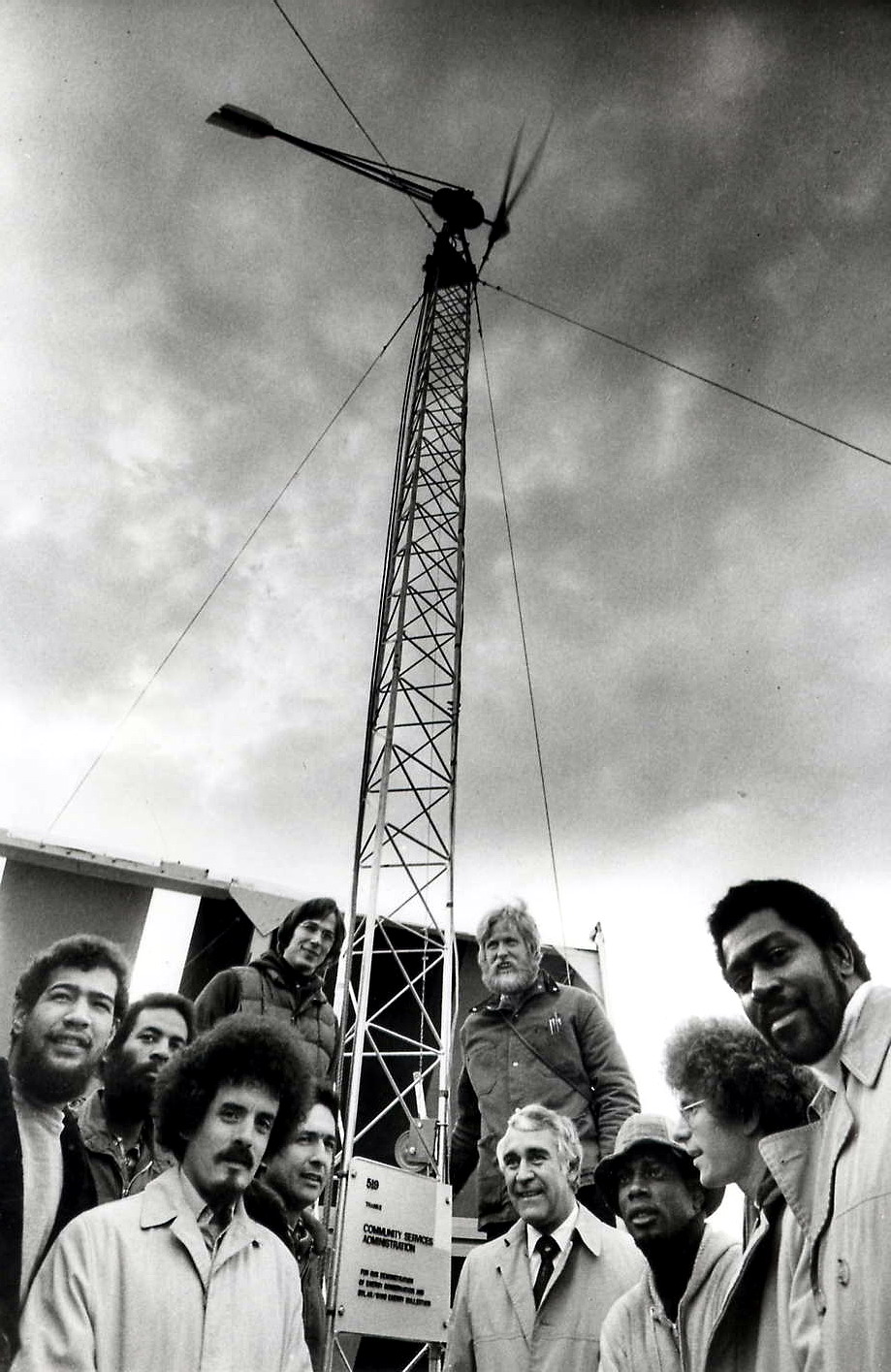

The building and its cutting-edge energy sources made for good news copy. During the initial burst of attention, politicos and celebrities, like actor Robert Redford, came by to take a look at and offer praise. “The MacNeil/Lehrer Report” did a segment on the building. Samuel Martinez, the director of the U.S. Office of Community Services (in first photo, bottom row, fourth from right), also visited to admire the project.

Fast-forward to today, and it’s been years since the solar panels and wind generator were actually working. In fact, about 10 years ago, the latter was taken down. The solar panels — whose solar collector was powered by the wind generator — were removed, as well.

More than 30 years after those heady days of 1977, many of the E. 11th St. pioneers gathered last October in the building’s backyard and attached garden for a reunion.

Karen Bermann was “an original crew member,” as she put it, one of the people who came together to fix up the dilapidated husk of a building under a city-funded program. It was one of the first so-called “sweat equity” projects, under which people who toiled to renovate the property then earned the right to live there.

Soon enough, though, they realized the job would be a huge undertaking.

“The landlord had set fire to it,” Bermann said. “It had burned 13 times. It was a terrible building we had chosen to rehab, but we were in too deep.”

A group of nine, they had met through a local food co-op. Bermann was 19 at the time and studying architecture at The Cooper Union.

“I was always up for an adventure,” she recalled. “We were paid $100 a week, that seemed enough to live on. The city gave us a municipal loan of $220,000.”

The rehab job took a few years. People without children who were “wild,” like her, she said, moved in first; families followed later.

“Back then, it was embarrassing to be from Brooklyn or Queens,” she recalled. “You could live in Manhattan back then. It was filthy, it was dangerous, but it was exciting and it was cheap. It was ‘Taxi Driver.’

“I was a lefty kid,” she said. “I heard good things about this community and I wanted to insert myself into it.”

Writer Michael Carter, who lives down the block and stopped by the reunion, concurred that the street used to do a bustling, if illicit, business.

“This block was the world headquarters of car-stripping,” he said. “The only cars that would come down here were limousines from Connecticut with rich kids who wanted to buy drugs.”

After they had been fixing up the E. 11th St. building for a year, Travis Price, a cowboy hat-wearing early solar advocate, turned up.

“There was an oil crisis in the 1970s,” Bermann said. “He asked us if we would put solar energy into our building.”

Two other grad students, from Yale and M.I.T., also got involved in the solar project. The solar panels on the roof would heat the building’s hot water. A wind generator — known by everyone as the “windmill” — was added into the mix, to provide electricity for the building.

Carlos “Chino” Garcia, a co-founder of the former CHARAS / El Bohio cultural and community center at the old P.S. 64, on E. Ninth St. and Avenue B, helped rally support for the project. He worked with Adopt-a-Building and was a member of the E. Sixth St. food co-op.

“Nothing really happens in the neighborhood without Chino,” Bermann recalled of Garcia’s influence back then. “He’s like the Godfather. Nothing happens without his support.”

The wind generator ultimately didn’t provide that much power, just enough to keep the lights on in the building’s hallway, lobby and basement. Nevertheless, what they created at the tenement opened people’s eyes to possibilities, and showed a hopeful glimpse of what could be done.

Naturally, though, Con Edison wasn’t very happy about it, rightfully seeing it as a challenge to its monopoly. The utility sued, arguing that the E. 11th St. building could damage the power grid.

“They didn’t want everybody putting up windmills and not needing Con Ed,” Bermann noted. “It conceivably could have started a rash of people putting up windmills and alternate energy.

“The goal was to run your own building — no landlords,” she recalled. “It was a dream…yes, ‘the people, the people.’ We were going to grow corn in the streets. We were not pro-squat. We were not artists. We were not anarchists. Most of the people who worked on it and lived here were people of color from the neighborhood. It was not a white people building. Some of the organizers were white. It was very grassroots.”

Bermann later moved out of the place in the mid-’80s when, according to her, the tenement was “going through a bad phase,” with a tenant who was dealing drugs.

“The building was in a lot of chaos,” she said.

She is currently an associate professor of architecture at Iowa State University.

Ruth Nazario, another original tenant, worked at Adopt-a-Building. She moved into 519 E. 11th St. in 1978, and lived there for three years. She moved out after the birth of her daughter, whom she had with Garcia, and now lives in California.

Nazario’s strongest memory of the wind generator was of all the people who came traipsing through to gawk at it.

“All these people went up to the roof to see it, from Japan, from Washington, from all over,” she said. “It was just a phenomenon.”

Price was in his early 20s when he was working on the E. 11th St. project. He said that, back then, solar power “was like talking about Mars.”

“The importance of that little building,” he recalled of No. 519, “those were the ‘radical solar days,’ as I call it. We were trying to be self-reliant. … I was the guy who told them, ‘Your energy bills are going to be bigger than your mortgage.’

“I thought, why don’t we do this with poor people first, and have a trickle-up, not trickle-down, theory?”

Although, in general, the wind generator didn’t provide that much power, on very windy days, its blades would spin so fast that “the [electric] meter would run backwards,” Price recalled.

Another indelible memory for him was the day a former U.S. attorney general came by after Con Ed had declared it was suing the building’s residents.

“Out of the blue, Ramsey Clark walked by the door and said, ‘This is the biggest thing since civil rights. I’m going to defend you,’” Price said. “Obviously, we knew we were breaking the law. But we had to break the law to change. The case showed you can co-generate to provide your own power.”

“Co-generation” means using a power source to generate electricity and useful heat at the same time.

Price said a movie about the building and its legendary wind generator is also now under consideration.

Price, who noted he is considered “one of the five godfathers of the green movement,” has gone on to a successful career in the solar industry as principal at Travis Price Architects.

He noted that the technology actually has its roots in military communications.

“The military invented photovoltaic cells,” he said. “The military invented the Internet. All these tools…when you’re in the field, you need communications.”

“President Nixon was really the first green environmentalist,” he added.

Conversely, he blasted Bernie Sanders as a hypocrite for flying around on a carbon-spewing jet plane during his last presidential campaign.

“What’s Bernie Sanders doing talking about global warming and paying $300,000 a month for a private jet?” he scoffed.

Michael Freedberg was one of the architecture grad students involved with 519 E. 11th St. in its early days. He had started working right out of school with the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. He and fellow recent Yale grad Phil St. George had the idea of turning over abandoned — known as “in rem” — buildings to people for low or no cost.

“My point was that it was more than just an energy project,” Freedberg said of No. 519, “more than just a housing project. It was part of a community-wide effort to save the residents — and the arts groups were part of that.

“[Actor] Luis Guzman was in the building. He did sweat equity. I remember we did the ‘Demolition Derby’ — we invited people over to knock down walls.”

Ultimately, the homesteaders were able to purchase the building for $100 per co-op unit, or $1,600.

And, in the end, they also defeated Con Ed. It was another big news story.

“The public utilities commission ruled in our favor and required Con Ed to buy [excess] power from us,” Freedberg said, referring to the New York State Public Service Commission. “They did put us on the front page of The New York Times.”

He was saddened, however, when the wind generator was taken down.

“I think it would have been good to find a way to keep it up there,” he said. “It was such a symbol.”

Today Freedberg is senior adviser for high-performance building in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Energy and Environment.

Rafael Jaquez, the co-op’s current president, moved into the building in 1980 as a 25-year-old. He said the use of the wind generator was discontinued by 1993, though the solar panels were still used for hot water.

Around 15 years after that, though, a tenant on the fifth floor began feeling “paranoid” about having the wind generator right on the roof above him, Jaquez said. The building hired an industrial engineer to check it out, but ultimately the iconic apparatus was removed.

“I was out of town,” Jaquez recalled. “I thought that was a big bummer. I think that more thought should have gone into it because it’s something that was really symbolic. I felt really devastated when I came home and saw the windmill was gone.”

He said he recalled when the East Village was like a “war zone,” and how seeing the wind generator rising above the rooftops was like a beacon of possibility and hope.

“This building was the first homesteader building movement,” he said. “So the windmill became like a torch that lit up and inspired a movement.”

Today, all that’s left of the wind generator at the address is a single blade. Vincent Barnes, a former longtime president of the building, found it, cleaned it up and painted it white from its original red.

“It’s a trophy,” he said.

At the reunion, the building’s residents, past and president, using a black marker, all signed their names on it.

Be First to Comment