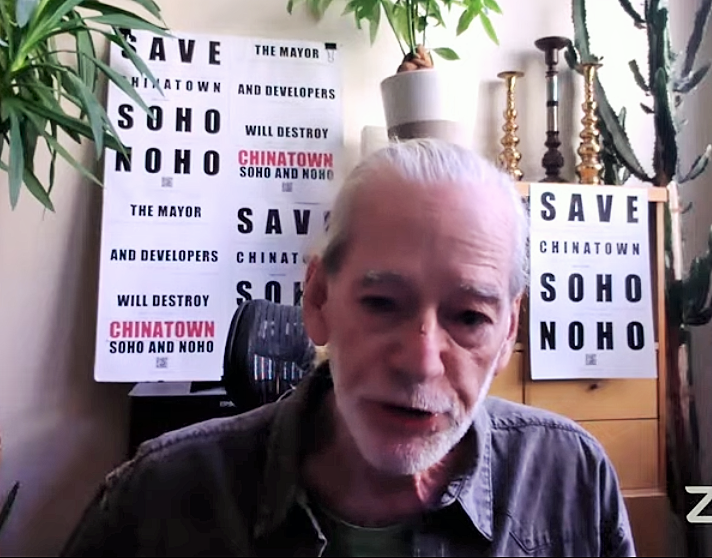

BY DASHIELL ALLEN | Pete Davies has lived in his Soho loft on Broadway since June of 1980. In 2005, eight units in his building — including his own — entered rent-stabilization.

The next year, the building’s owner applied for a special permit through the Department of City Planning to add additional Joint Live/Work Quarters for Artists. They also had the novel idea of building penthouses on top of the roof.

Davies and his fellow residents were immediately concerned. The building, originally built in 1844, “wouldn’t hold anything on the roof, unless you put in a new superstructure,” he explained, “which means you’d likely drive steel down to the foundation from the roof, and somebody’s loft is going to get steel driven through it.”

If that had occurred, residents would most likely have been displaced — either temporarily or permanently — if the building became structurally unsound.

Alongside fellow residents, Davies made his case to the City Planning Commission, “who had been looking at their application for a year and never called this out,” he noted. The commission eventually determined that the owner couldn’t build higher, as they had already maxed out on the legal height based on the currently zoned floor area ratio (F.A.R.).

“Great, the building is maxed out, we’re safe, that’s something we never have to worry about,” Davies thought at the time. But that all changed this year.

Now, Davies is concerned about the possible ramifications of the city’s Soho/Noho upzoning plan, which would allow developers to build taller buildings along Broadway, where he lives, and could give the owners of buildings like his an incentive to further develop — and in the process displace — rent-regulated tenants.

The City Council’s Zoning Subcommittee will hold a virtual hearing on the Soho/Noho rezoning on Tues., Nov. 9. While the meeting will start at 10 a.m., the discussion of the rezoning is not expected to begin before 11:30 a.m. It will be the public’s last chance to weigh in on the contentious proposal that the administration is desperately trying to push through before Mayor de Blasio exits City Hall at the end of this year.

The city’s plan increases the allowable size of both commercial and residential development throughout Soho and Noho — especially within three areas designated “opportunity zones.” Those increases would likely incentivize commercial development, including big-box retail, nightclubs or even New York University dormitories, according to multiple sources.

The rezoning would also impose a $100 per square foot “flip tax” on certified artists living in Joint Live/Work Quarters (J.L.W.Q.A.) should they wish to sell their loft apartments to nonartists or obtain a certificate of occupancy a.k.a. “C of O” from the Department of Buildings.

That worries longtime artist residents like painter Leigh Behnke, who has owned her loft off Broadway since 1984.

“We worked really hard to get our C of O under the conditions that were set,” she said. “We would have to do a gut renovation of the whole building. It will force people to lose their homes… . You cannot convert a building into something that it’s not architecturally. We don’t have the proper egress for the new standards.”

Both Behnke and Davies are members of the Broadway Residents Coalition, a community of Soho residents living along Broadway that formed in the late ’90s in opposition to big retail developments, originally to “find a way to live in more peace and harmony with the retail that was slowly beginning to come into the neighborhood.”

Bhenke teaches classes at the School of Visual Arts. She recalled that Soho was so undesirable when she first moved in that she “had free rent for a year.”

“People, you know, even before they got their bathrooms together, they’d just have a pipe in the floor,” she said. Her and her neighbor’s lofts were divided by “just a curtain across, until we built a wall.”

Those are just two examples of the creative adaptation that artists at the time underwent to convert former light-industrial factories and warehouses into permanent homes.

Now, after adapting her space and obtaining a certificate of occupancy allowing her to live and work there, Behnke finds the upzoning’s proposed flip tax punitive.

The past year has been marked by numerous hours-long public hearings held be Community Board 2 and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, in which the plan’s opponents, like Behnke and Davies, state their case, followed by proponents who argue the upzoning would create housing under Mayor de Blasio’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (M.I.H.) program.

Denny Salas, a former City Council District 1 candidate who lives near Soho, supports the upzoning but is also sympathetic to longtime residents’ concerns.

“From their perspective, I would feel like I’m getting targeted,” Salas said, referring to J.L.W.Q.A. residents, adding that he thinks the flip tax should be modified.

He also agrees with Behnke that the plan as currently written would incentivize big-box retail and commercial development.

“The commercial density allowance is too high,” he said, “and that would encourage developers to really focus on office buildings and in commercial businesses rather than actually building housing.”

“The plan that they’re putting forward is akin to a central business district but with quirky things around the edges,” said Davies, also referring to the commercial density increase, which in some of the upzoning’s “opportunity areas” is practically the same level as the would-be residential — 10 F.A.R. compared to 12 — both akin to the zoning in many parts of Midtown, which suggests that commercial, rather than residential, development would be built.

There’s also no question that the plan released by City Planning differs greatly from that proposed by the pro-development and housing group Open New York back in 2019. The Open New York plan makes no mention of commercial development, flip taxes or a vaguely defined arts fund, though does mention, albeit in passing, “preserving the cast-iron buildings that make the neighborhoods unique.”

If the city’s plan were to pass as it currently stands, Salas would not support it. Still, he is hopeful that if the amount of commercial density it allowed were decreased the plan would bring in more housing.

“I do believe that every neighborhood across the city needs to be socioeconomically diverse,” he said. “One of the things we can do by rezoning Noho and Soho is offer working-class families access to high-opportunity areas, access to better schools, and allow them the opportunity to climb that socioeconomic ladder.”

When he was growing up, Salas’s parents, who were working class, broke the law to send him to a fancy school in a neighboring town, which he says he benefited from.

“When you take kids from lower-income areas and put them in these higher-socioeconomic neighborhoods, all of a sudden they end up doing a whole lot better,” he said.

“M.I.H. is the only tool right now that’s being used” to create even 25 percent affordable housing, Salas said. “Noho and Soho is really going to be a test to it. I think offering tax subsidies for developers in order to create permanent affordable housing is actually good policy.”

Many Soho and Noho residents might agree to try out the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program in their neighborhood, albeit at a lower density, as is proposed in the Community Alternative Plan spearheaded by Village Preservation.

But, for a variety of reasons, they don’t want to see an encroachment of high-rises, which could either be 75 percent market-rate luxury housing with 25 percent so-called affordable units for a single persons making as high as $108,680 annually at the area median income of 130 percent.

Zishun Ning, an activist with the Chinatown and Lower East Side grassroots group Youth Against Displacement and the Chinese Workers Association, opposes the rezoning because, he said, “it encourages luxury high-rises” in one particular opportunity zone referred to by City Planning as “Soho East.”

While there has recently been debate over whether the area in question, east of Lafayette Street and north of Canal Street, is actually in Chinatown, it falls squarely within the Chinatown Business Improvement District and is also home to the Museum of the Chinese in America, which Ning’s groups have been regularly protesting against.

“If you upsize in one area you affect the surrounding area as well, so that will go beyond just the upzoning area into the neighboring buildings of Chinatown,” Ning said, predicting the upzoning would lead to higher real estate taxes, plus displacement pressure on existing rent-regulated tenants.

“I don’t think you should be upzoning historic districts,” said Emily Hellstrom, a Soho resident who is also a residential member of the Soho Broadway Initiative business improvement district.

At the same time, she said, she’s willing to compromise.

“I think the residents have really been painted into a place where people say they’re obstructionist, they don’t want anything, there’s nothing that they’ll compromise on, all this stuff. And it’s really not true,” said Hellstrom, pointing, for example, to the Soho BID’s effort to bring commercial owners and residents together.

She would also like to see other opportunities to create housing in the area taken seriously, such as the proposal to develop the site at 2 Howard St. currently occupied by a parking lot used by the federal government.

Back in February, Community Board 2 Chairperson Jeannine Keily asked Senator Chuck Schumer during a Zoom meeting if it would be possible to develop the site after completing a land transfer with the federal agency — and he said yes.

More recently, according to a source familiar with the subject, a different agency connected to President Biden’s initiative to create affordable housing expressed interest in creating permanent affordable housing on the site “to create equity.”

Christopher Marte, the incoming District 1 city councilmember, said it’s time to seize the opportunity on the Howard Street spot.

“It’s something that I want to really be super-aggressive about going into next year,” he said, “because if you know D.C. is ready to move on it, we should just jump on it and start working.”

Marrte added that he supports “using the site to bring equity to a majority-white, affluent community” — in other words, fulfilling the goals set forth by City Planning.

There are differing views among opponents and proponents of the rezoning, but largely they almost seem to be having two separate conversations. Residents like Behnke and Davies are worried they may be displaced, or that their quality of life could drop significantly, while upzoning supporters like Salas simply want to see more housing constructed.

The plan’s biggest supporter, Open New York, whose recent posting mentions the issue of commercial density while simultaneously encouraging the public to “e-mail your councilmember in support of the rezoning,” did not respond to a request for comment.

In September, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer balked at supporting the rezoning for Soho and Noho.

“I cannot support the rezoning as it stands,” Brewer reiterated in a statement to The Village Sun. “We can do better than the current proposal. Commercial F.A.R. must be reduced, the historic district must be preserved, subsidies must be provided to developers who exceed M.I.H. guidelines, and Loft Law tenants must be protected.” She added that she is “continuing to ensure that the NYC Council’s Land Use team is aware of these concerns.”

It was Brewer, along with Councilmember Margaret Chin, who initiated the rezoning process — which was not initially intended or pitched as an upzoning — with the Envision Soho initiative.

Davies, Behnke and Hellstrom were all part of the Envision process from the very beginning.

“I even opened my loft for one of these meetings,” said Behnke, because the city “wanted to see what an artist’s loft looked like that hadn’t been renovated yet.”

“They put us through this whole process,” she said, “and then all of a sudden they came up with this plan, which to us looks very pro-development and pro-retail.”

Be First to Comment