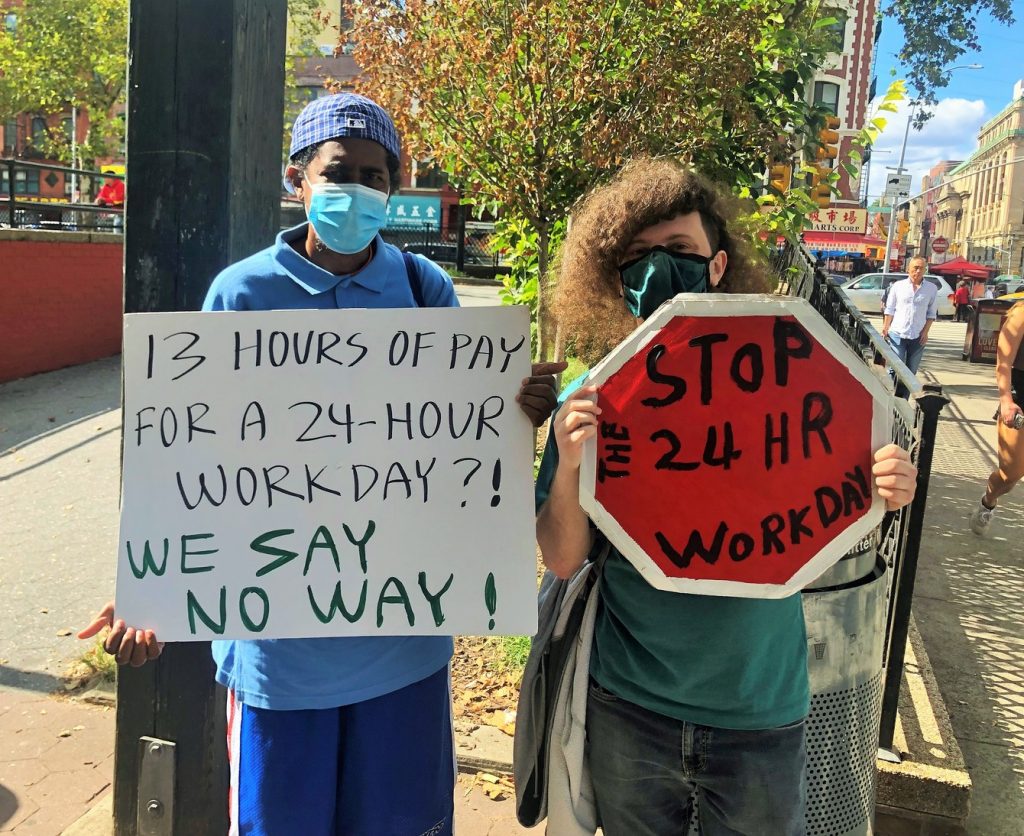

BY DASHIELL ALLEN | Melania Batise spent 12 years as a homecare attendant, working physically and mentally grueling 24-hour shifts.

“My mind would go cloudy after being inside so long,” she said. “I didn’t know where I was, or where I was going. When I got to sleep in my own house, I dreamed that I was still with my patient, and screamed her name out loud.”

On Sunday, Batise joined dozens of other home attendants to protest the 24-hour workday in front of the offices of the nonprofit Chinese American Planning Council (CPC) in Chinatown.

“Twenty-four hours destroys families,” she said. “It destroys my relationship with my children, with my partner.”

Another home attendant, Chu Mai Kong, told a similar story: “Both my hands are disabled, I cannot lift anything, I have insomnia and now my physical condition is getting worse,” she shared.

Hundreds of Lower Manhattan residents and activists took to the streets of Chinatown in solidarity with the workers.

“No more 24!” they chanted. “Chinatown not for sale! How do you spell racist? C-P-C! How do you spell racist? M-O-C-A!”

The March Against Displacement And Racial Violence, organized by the grassroots organizations Youth Against Displacement and Youth Against Sweatshops, brought together the campaigns against CPC to end the 24-hour workday for home attendants and the unionized Jing Fong restaurant workers’ picket of the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA).

“MOCA and CPC are two of the biggest perpetrators of racist violence,” activist Jihye Song said. “They destroy their own community, they kill their own workers to fill their pockets. They exploit us, stealing our homes, our health, our lives. Twenty-four-hour workdays and displacement kills us”

CPC, which employs thousands of 24-hour home healthcare attendants, is officially against the 24-hour workday, per a recent op-ed by C.E.O. Wayne Ho, who supports state Assembly bill A3145, which would ban the practice.

But the workers and activists want accountability now. The workers, who are only paid for 13 hours, demand back pay from the nonprofit. And they say it’s within CPC’s control to end the destructive practice — by implementing two 12-hour shifts to replace one for 24 hours.

Democratic City Council nominee Christopher Marte, whose mother worked as a home attendant for 20 years, said that the workers’ testimony described his childhood.

“This is the trauma, this is the harm that agencies like CPC impose on home attendants,” he said. “And when we look at the home attendants, 90 percent of them that experience wage theft are immigrant women of color.”

“Over the past year we have seen agencies settle with home attendants,” he said. “However, the biggest abuser of this, CPC, hasn’t settled. If it’s impossible to settle, why are other agencies doing it?”

The activists are also protesting MOCA — incidentally, a community partner of CPC — for accepting $35 million from the city that they charge was in exchange for the museum supporting a new megajail in Chinatown, through a deal brokered by Councilmember Margaret Chin.

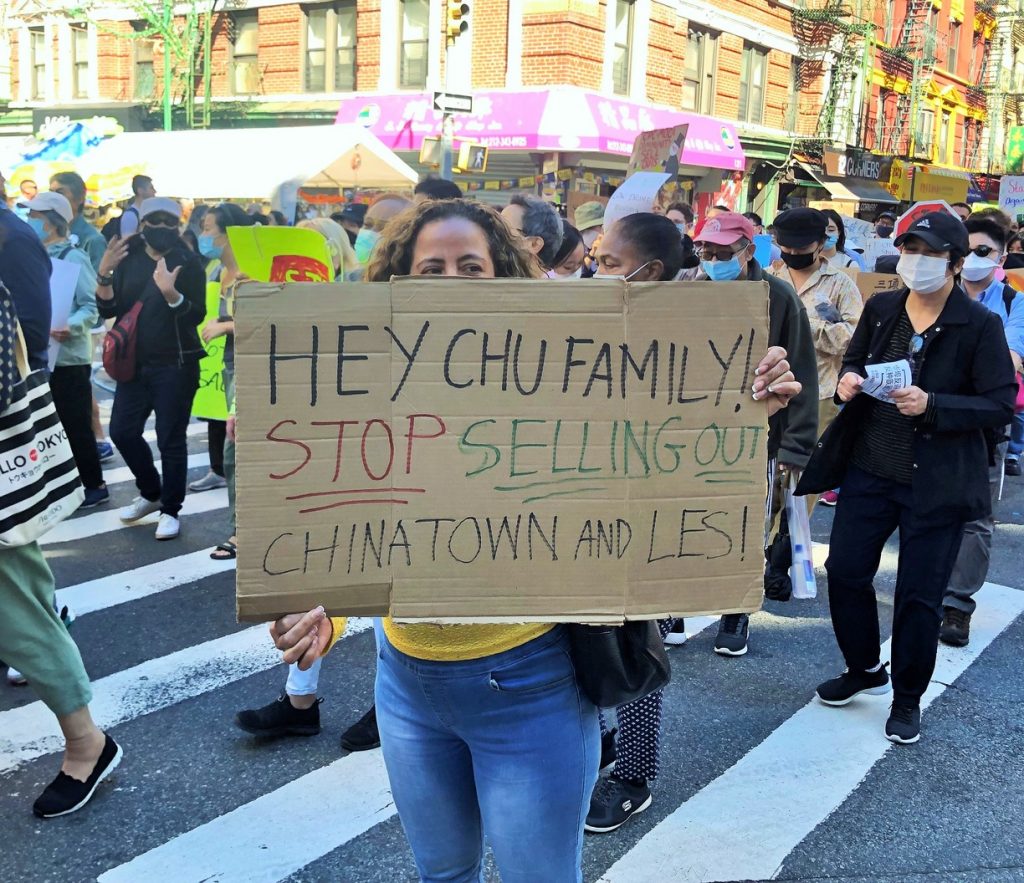

The activists are also calling out major Chinatown property owner Jonathan Chu, who chairs MOCA’s board and who owns the building formerly occupied by Jing Fong restaurant. When the dim sum palace closed in March, more than 180 unionized workers suddenly found themselves without a job.

The protests in front of MOCA, which have been ongoing since March, will now be taking place five times a week. A GoFundMe was created Sunday to support the Jing Fong workers.

All along Elizabeth Street shopkeepers and tourists stopped what they were doing to watch the protesters march by, as they made their way toward the Museum of Chinese in America on Centre Street.

As the protest advanced, the chants slowly shifted from, “No more 24!” to “Protect Chinatown! Save Jing Fong!”

“Chinatown not for sale! Lower East Side not for sale! Soho not for sale! Noho not for sale! New York City not for sale!” the protesters shouted, referring to the hotly opposed developer-driven proposed Soho/Noho rezoning.

“Jonathan Chu, shame on you!” they chanted at another point. “How do you spell racist? M-O-C-A”

Youth Against Displacement activist Zishun Ning addressed the crowd in front of MOCA.

“MOCA and CPC — they are the ones who will beat you and say, ‘Stop Asian hate,'” he scoffed. “They will force home attendants to work 24-hour workdays and say, ‘I love you.’ They will accept the bribe from Mayor de Blasio and say, ‘Well, there’s nothing we can do.’ They will insult the seniors and then put the portraits on their storefront. How dare they?

“They are doing the work that open racists can only dream of,” Ning railed. “They say, ‘White supremacists can exploit Chinese, why not us?’ In the Black community people call this Uncle Tom. In Chinatown, we have Uncle Chu, the biggest landlord in Chinatown.”

Lai Ye Chen, a garment and homecare worker who has toiled through eight years of 24-hour workdays, said that the homecare and restaurant industries are two of the largest employers within the Chinese communities.

“As a member of the community, MOCA’s board members and its directors should have done their best to help the restaurant industry,” she said. “But MOCA’s board chairperson, Jonathan Chu, took advantage of the pandemic and closed Chinatown’s iconic Jing Fong restaurant. At the same time, he says that he represents the Chinese community, only to turn around and sell us out in supporting the city’s soulless jail construction right here in Chinatown.”

“What MOCA is doing hurts me, hurts the Lower East Side, hurts Chinatown, it hurts all of New York,” said Tony Kailin, a Lower East Side resident. “It’s totally racist. MOCA and Jonathan Chu are promoting racism.”

Kailin connected the protest against MOCA to the actions of other landlords and developers in Chinatown: “What do you call it when landlords and developers come here and evict families, babies, seniors, longtime residents from their home on a winter night?” he said. “Isn’t that violence?”

That’s what happened to the residents of 85 Bowery, who were evicted from their homes in 2018.

In response to activists’ allegations, MOCA released a fact sheet in August, refuting some of the claims of the so-called “small network of neighborhood activist groups”: The museum said it has “steadfastly opposed jail construction in Chinatown,” and that it would be “wildly irresponsible of MOCA as one of the more notable community cultural and historical institutions to reject vital City funding.”

As for board chairperson Jonathan Chu, the same statement describes him as “an active and highly supportive MOCA board member, as well as a community advocate, business owner, longtime economic contributor, public servant and volunteer to several not-for-profit efforts.”

Siyan Wong, a visual artist and workers’ rights lawyer, said she refuses to have her art displayed by MOCA.

“We need a voice and this museum is not giving us a voice,” she accused. “It’s acting against the interest of working people, against the interest of most people in the city of New York.”

Wong, along with the Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side and the Peter Kwong Immigrant Workers Learning Center, is organizing an “art exhibition against displacement” with an open call for submissions until Oct. 4.

Representatives from across the city attended the march in solidarity.

“I came down here to support the workers,” said state Senator Robert Jackson, who represents Washington Heights and the Upper West Side. “Displacement is happening everywhere and we must fight it.”

Be First to Comment