BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Michael Armstong, former publisher of The Villager and the Brooklyn Phoenix newspapers and an outsize presence in the civic life of Brooklyn, died at Methodist Hospital on May 4. He was 79.

The cause of death was coronavirus.

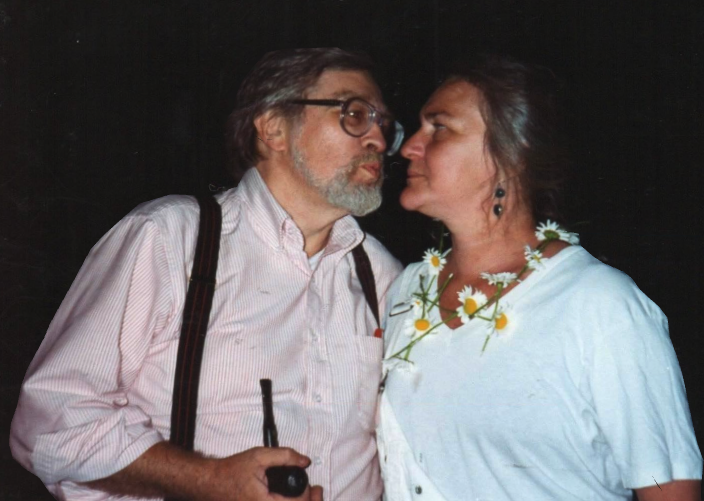

His wife, Dnynia, had also died from the virus, a month earlier, at age 80.

Armstrong’s daughter, Arija Noel, said Dnynia had been doing a drawn-out rehab for mobility issues at Cobble Hill Health Center, the Brooklyn nursing home that has had 55 deaths attributed to COVID-19.

Armstrong visited his wife there constantly, bringing her food and often spending the day with her. Later — after he could no longer go inside for safety reasons — he visited with her during her transports outside the nursing home for dialysis several times a week.

“He was working so hard to bring her home,” his daughter recalled. “He got to see her the day before she went into the hospital. They had told him he should get tested because he was with her that day.”

But he was afraid to go in and get tested.

“He knew if he went into the hospital, he wouldn’t come out,” she said. “He got sicker and sicker.”

Dnynia died on April 4, also at Methodist Hospital. Around two weeks later, her son, Adam Bauman, found Armstrong at his home, gravely sick, his daughter said. He was admitted to the hospital I.C.U., where he was sedated and spent 18 days on a ventilator battling the disease. He had entered the hospital with kidney failure, which subsequently cleared up, but his lungs were just too filled with COVID, his daughter said.

Noel, who flew in from Spain, where she lives, used FaceTime to read to him. Although the hospital only had one iPad for two floors of patients, the volunteer services coordinator, Wendy Freund, had worked as a reporter in Brooklyn Heights and knew Armstrong. She made sure the iPad was available for Noel to use with her father. Noel would use it late at night for several hours at a time.

Since he loved mysteries, his daughter read him an Inspector Lynley mystery by Elizabeth George. He also loved trains, so she sent him on virtual train trips.

“Hopefully, he could hear the whistles and the tracks,” she said. “I described it to him.”

She also played him classical music.

They made it halfway through the Lynley mystery.

Michael Armstrong grew up in Galion, Ohio, with stints also in Alaska, Kentucky and Oregon, as the family relocated as his Army major father was reposted around the country.

He attended Pacific University, in Oregon, where he met his first wife. He then went on to get a master’s degree at Boston University.

Arriving in New York City in the 1960s, Armstrong landed a job at Ruder Finn public relations, where his interest in politics soon asserted itself.

“He had the Democratic National Convention account,” his daughter recalled.

In 1970, Armstrong, not yet 30, took a leave from Ruder Finn to manage a political campaign — attorney Pete Eikenberry’s run for Congress — and never went back. With Armstrong’s help, the reform Democrat mounted a strong race for Brooklyn’s 14th District, narrowly losing to longtime incumbent John Rooney.

“I lost by 1,100 votes,” Eikenberry told the Brooklyn Eagle, “which was an astounding feat against a 24-year incumbent… . [W]ith a third candidate in the primary, Armstrong’s brilliant management helped me get 43 percent of the vote. Rooney got 46 percent.”

Around the same time, Armstrong himself ran for Assembly and nearly won, after taking the spot of a candidate who had dropped out, according to his daughter.

He started the Brooklyn Phoenix in the early 1970s and owned it through the early 1990s. The paper became synonymous with the revitalization of Brownstone Brooklyn.

“He covered Brooklyn. He loved Brooklyn, everything about it,” his daughter said. “He was always trying to find ways to make things better. He was on all kinds of boards. If it was Brooklyn, he was involved somehow.”

In 1977, Armstrong took over The Villager, Greenwich Village’s weekly newspaper, owning it until 1992.

The Villager had a small office that relocated a few times, including onto E. Fourth St. At the start, Armstrong would be there a few times a week, but he spent most of his time at the Phoenix’s office, on Atlantic Ave. In those pre-Internet days, copy typed up at The Villager office was physically taken to the Phoenix office for production, recalled his daughter, who sometimes performed the role of copy courier.

His daughter also remembers fun office parties in the mid-’80s at Garvin’s, a Downtown restaurant that was a steady advertiser in The Villager and boasted its own fortune teller.

In 1981, Armstrong married Dnynia Bauman, who was working at the Phoenix on the advertising and business side. She became the enduring love of his life.

For a few years in the mid-1980s, Armstrong also had a monthly paper in the Hudson Valley, the River Valley Chronicle.

At The Villager, he expanded the arts section, pushing the paper’s coverage into the creatively vibrant East Village. He launched the Village Theater Awards for Off-Broadway and experimental theater. He was also involved with the first folk festivals in Greenwich Village, according to his daughter.

Armstrong’s newspapers were award-winning in their own right, often winning Best Coverage of the Arts in the New York Press Association’s annual Better Newspaper Contest.

In the early 1990s, Armstrong went to work in P.R. for Brooklyn Borough President Howard Golden while Dnynia took over the running of the Phoenix.

“He, just a few months ago, wrote a speech for [Golden],” his daughter noted.

Armstrong also did P.R. for Queens Assemblymember Margie Markey, and was a big advocate of her Child Victims Act, his daughter said. The bill kept passing the Assembly but always stalled in the state Senate, until it was finally passed last year, with state Senator Brad Hoylman as a primary sponsor.

Armstrong also did P.R. for Assemblymember Adele Cohen.

At one point in the ’90s, Armstrong had the idea of turning The Villager into a collaboration with New York University, Noel said. The plan was that he would also teach at N.Y.U. — but there was one hitch: He needed to have completed a thesis. After checking with Boston University, it was determined that he had not actually done one in graduate school. So, at that point, he started mulling whether to do a thesis. Ultimately, the idea didn’t pan out.

Community newspapers are often run on a shoestring, and eventually The Villager ceased publishing for a period. Tom and Elizabeth Butson, friends of the Armstrongs who lived nearby in Boerum Hill, bought the paper out of bankruptcy and revived it.

After Golden retired from politics, Armstrong landed a P.R. job for Independence Community Bank. He later created Armstrong & Associates, a media and marketing company.

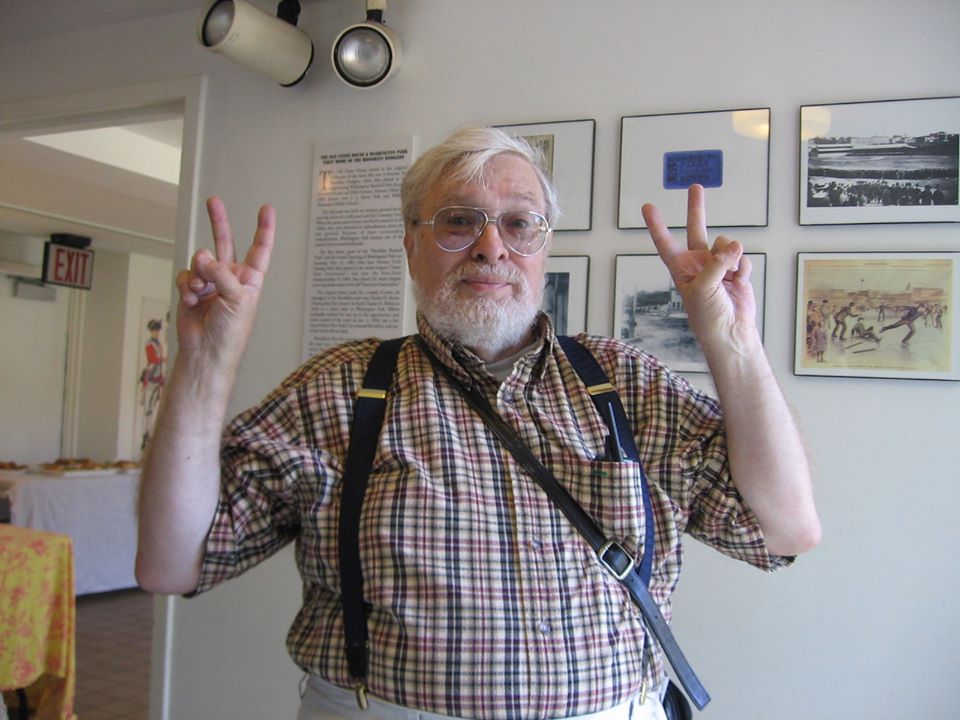

Armstrong was highly literate and he loved photography, both of which made him well suited for newspapers and P.R.

He was a voracious reader.

“His Kindle became like a second hand to him,” Noel said.

During his newspaper days, he was especially passionate about photography.

“He kept every single photo every Brooklyn Phoenix photographer took,” his daughter said, noting he eventually donated the paper’s photo archives to Brooklyn College. He was still eagerly waiting for the photos to be properly archived.

When he got into using Facebook, Armstrong started posting a daily “picture of the day,” relishing the comments he would get on them and the interaction with friends and family.

“He loved to take pictures,” his daughter said. “He took pictures of everything.”

He was also a big walker.

“He walked everywhere,” she recalled. “He liked to see the city and what was going on.”

Over the years, Armstrong was on many boards, including of the Brooklyn Arts Council, Old Stone House Museum, Prospect Park Alliance, Brooklyn Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, Atlantic Avenue Local Development Corp. — the parent organization of the Atlantic Antic — and New York Press Association.

Friends and colleagues paid tribute to his contributions to community newspapers and the civic and cultural life of Brooklyn.

Elizabeth Butson said she was close friends with Armstrong earlier in her life.

“Mike gifted Brooklyn with a great weekly newspaper he created, the Phoenix,” she said. “It was probably the best community weekly in the country. The quality of the paper was phenomenal. Mike was really brilliant. Everybody waited to get the paper in the mail. It was Downtown Brooklyn. Great writing.

“The Villager was bought and sold several times after the original owners failed to understand the shifts in society in the ’60s and ’70s. The Village Voice, with young talent and financial backing, swept away The Villager readers.

“Mike made a valiant effort to save The Villager, but could not raise the necessary funds and ceased publishing.

“He asked Tom and I to buy the paper, so that it could continue being the paper of record for the community. We were very supportive, Tom and I, of the Phoenix. That’s why Mike wanted us to get The Villager.”

In a Facebook post, Ed Weintrob, the founder and former publisher of the Brooklyn Paper, called Armstrong’s launching of the Phoenix “a milestone” for Brooklyn:

“Mike and I were longtime competitors who approached journalism from somewhat different perspectives,” he wrote. “[But] we each took to press an independent spirit and a desire to pursue — and ultimately discover — truth, sharing a mutual respect for the importance of our craft.

“His creation of the Phoenix was a milestone not only for Brooklyn journalism but for Brooklyn itself, contributing mightily to the literal resurrection of our borough in the 1970s and ’80s and spawning many talented journalists in the process.”

George Fiala, the publisher of the Red Hook Star-Revue, was general manager for Armstrong, selling and overseeing advertising.

“Most of what I know about putting together a newspaper is from working for Mike for 10 years,” Fiala said, “like so many who made their career in the newspaper business after starting out at the Phoenix or The Villager. And all of us said that every other job we had after working for Mike was easy. You really learned your chops with him. I have lost someone who was almost like a father to me.”

Brian Patrick O’Donoghue, now a journalism and communication professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, was a reporter for Armstrong. Among the stories he covered was the dramatic destruction of Adam Purple’s famed Garden of Eden.

Brooklyn Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon said the Armstrongs had a profound influence on the borough.

“Brownstone Brooklyn owes much of its feel and character to Michael Armstrong and Dnynia Armstrong,” she said. “They were wonderful neighbors and good friends.”

David Siffert, president of the Village Independent Democrats, served with Armstrong on the board of Friends of Marcy Houses. Co-founded by Armstrong’s longtime friend Pete Eikenberry, the organization provides services to children in Bedford-Stuyvesant’s Marcy Houses.

“Mike was a force of nature,” Siffert said. “He was deeply committed to his community, but more than anything, he was deeply committed to journalism. He viewed journalism not just as a means of conveying information, or a mere tool for exposing misconduct, but as a true solution to many of the world’s most pressing problems.

“People bandy about the phrase ‘knowledge is power,’ but Mike lived it. He wanted everyone in our community to have the knowledge necessary to affect change, and he never despaired of the possibility of positive change. He fought fiercely for it every day of his life.”

Although Michael and Dnynia’s children were from previous marriages — from “three fathers and two mothers,” as Noel put it — they saw them as one big blended family.

Michael Armstrong is survived by his daughter, Arija Noel, as well as Dnynia’s son, Adam Bauman, and daughter, Aisha Ricca, along with six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

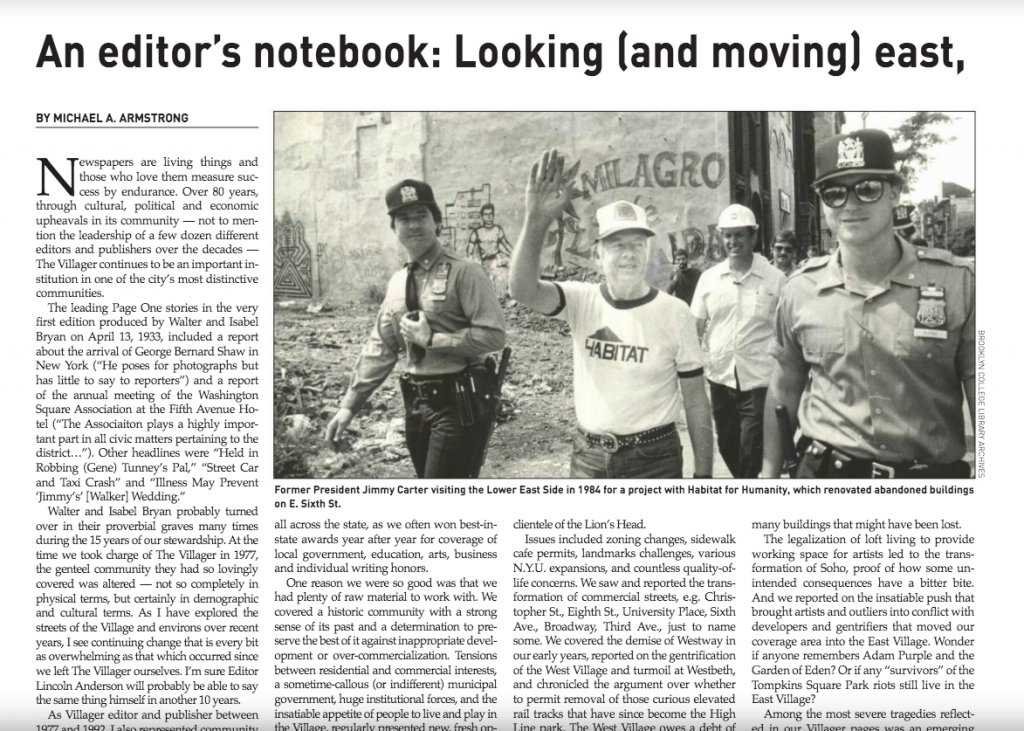

In 2013, Armstrong contributed a piece for The Villager’s 80th anniversary issue. In it he shared his recollections of running the paper for 15 years, some of the stories and events of the times — the start of the Village Halloween Parade, the 1978 newspaper strike, the AIDS crisis — and his thoughts on the essential role of community newspapers in the life of a community.

Referring to The Villager’s annual tradition of winning awards, he wrote, “One reason we were so good was that we had plenty of raw material to work with. We covered a historic community with a strong sense of its past and a determination to preserve the best of it against inappropriate development or over-commercialization.”

Mike was truly a mentor. He and Dnynia were caring, community-minded, hard-hitting journalists. Their guidance working for The Villager and, occasionally, the Phoenix, shaped my whole career from the Lower East Side to Alaska.

One thing I forgot to mention – Mike’s most enduring lesson he gave me – that the purpose of a community newspaper is to explain to the reader what is going on around them. Not in the world, necessarily, but right there in their neighborhood.

One of the great blessings in my professional life was Michael Armstrong. Constantly curious, always good-humored. His eye for a poignant picture was matched by unrelenting humanity. His skill as an editor spot-on. Mike and Dnynia will be well-regarded in heaven; they certainly are in our hearts.

Thank you, Lincoln, for such a thoughtful and thorough remembrance.

I guarantee you The Villager won’t be winning any awards anymore. Since Schneps Media bought it, along with AMNY, Metro NY and others, the papers have become uniformly bland, boring, corporate-friendly wastes of paper, fit only to line the bottoms of cat litter boxes and birdcages. Such a shame, and a real loss. RIP, Mr. Armstrong, and thank you.