BY CASEY EPSTEIN-GROSS | In May, the Ice Theatre of New York, at its annual gala, honored two prominent New York alumni for their remarkable work in the world of ice skating: Darlene Parent and Wade Corbett.

“If you look back on their lives — both Wade and Darlene, their whole lives have been about service in figure skating, in the New York figure skating community,” said Marni Halasa, a skating instructor at Sky Rink in Chelsea, where both ice veterans teach.

Few people alive today can say they’ve done something no one has ever done before, and even fewer can say they’ve done something no one will ever do again. Parent, creator of “toe skating,” is likely one of the only people who can say just that. Toe skating is a form of ice skating using ballet pointe shoes that Parent transformed into skates and which no one other than her has ever successfully done.

“[Parent’s toe skating] breaks boundaries,” said Halasa, who has known the fellow skater for 30 years, ever since the former saw the latter skating for fun at Sky Rink one day and immediately asked her to be a skating school teacher there. Halasa, despite originally pursuing a career in journalism, has been coaching skating there ever since.

“When people watch [pointe skating], they don’t think it’s going to be possible,” Halasa said. “It’s so crazy and so beautiful — who can balance on the toe like that? To this day, there’s nobody else who has done this except for Darlene… . Honestly, anyone else who tried it would probably break their ankles.”

The reason skating on pointe is so unimaginable for anyone else is that it requires someone with Parent’s specific history, not only with ice skating but with ballet.

“I was, first of all, a ballet dancer,” she said.

But when she was 5, her aunt took her to see the Ice Follies, and she immediately knew she had found what she wanted to do.

“I fell head over heels in love with skating,” Parent recalled. “My aunt and uncle, every summer — I still have the old programs — took me to Ice Follies, and I was drooling over it.”

Despite her desire to skate, her family wouldn’t let her for nearly a decade.

“I was 14 and a half when I put on my first pair of skates,” she recalled.

But, during the interim, she trained extensively in ballet. So when she finally got on to the rink, many of her instincts stemmed from her dance training — some of which helped, and some she had to struggle to unlearn.

Although the transition from ballet to ice skating may seem like a natural one, it’s actually rather uncommon. As Halasa put it, “The two worlds are extremely separate.

Parent agrees, saying that most skaters “skate because they don’t like ballet… . And the dancers still want to dance, so not many go for skating. There are very few who do them both.”

And even in the small center of that Venn diagram, fewer still would be capable of even attempting pointe skating: Parent’s technique requires not just experience in both ballet and skating, but mastery of both. Halasa elaborated on this, noting, “In order for others to do that, they would’ve had to master ballet first and then transfer to figure skating — which, just the dedication, the commitment, the skill… . It’s crazy to think about!”

Parent didn’t just successfully attempt pointe skating, though; she created it entirely. She had to figure out how to make the special skate itself through trial and error. Her first attempt with aluminum broke right away. The she had to find someone to actualize her newly conceived design.

“She created an art form and a performance outlet that only she could master,” Halasa said. “Nobody else could do it except for her,” just as no one but her could have imagined it.

Parent inspired countless skaters and dancers to follow her example, to create their own unique forms based on their own experiences. As Halasa put it, “She totally inspired me.”

After seeing Parent’s toe skating, Halasa — who had spent 13 years performing with a bellydancing company — decided to create a new form of her own, one that merged skating with bellydancing: She would skate with a candelabra on her head, performing her “bellydancing on ice extravaganza” wherever she could, something she never would have even thought of doing if not for Parent’s example.

Parent may be best known for her pointe skating, but she’s an inspiration both on and off the rink.

“Parent is an example of how one person can change people’s lives for the better in a truly meaningful way,” Halasa said. “She’s always helping — helping skaters, helping with Chelsea Piers, helping with the test sessions.”

This was the first thing I myself noticed about Parent. When trying to set up a time to speak with her, it became clear how involved she is within her community and how much time and energy she devotes to the people and causes around her. She was in charge of a test session on the day I suggested meeting, but said she’d be able to speak later that week — in the afternoon, because she teaches in the mornings.

“Who teaches at 6 o’clock in the morning and then helps someone campaign at 10 o’clock, handing out comp cards for two hours, and then heads back to the rink to coach, and then spends several hours at the Sky Rink front desk to organize test sessions?!” Halasa exclaimed. “Like, who does that?! And she’s 83 years old!”

Despite eliciting the awe of everyone around her, Parent herself sees nothing special about her generosity. To her, she’s simply passing forward the kindnesses people once paid her when she was starting out.

“People helped me at the beginning,” she recalled. “There are a lot of kids born with silver spoons in their mouths, and I was not. So I want to give back. And that’s what I’m doing. My family never could afford a lot of lessons… . So when kids show talent and they don’t have money, I teach them.”

For instance, one of her current students is a 16-year-old from Romania hoping to get his green card and continue skating in New York.

“His parents don’t have that much money, so I give him a lot of extra time,” Parent said. “They do pay me for part of it, but there’s a couple of people that pay me nothing for their lessons.”

She hopes to give them not only the opportunities she had available to her, but even more: Back in the heyday of her performing career, she auditioned and got into Ice Follies — her childhood dream — but couldn’t do it; she needed to care for her mother and didn’t have the money or ability to do both. As a result, Parent does everything she can to make her students’ dreams possible for them, regardless of socioeconomic status.

Whether inventing a brand-new kind of skate, pioneering an entirely new style of skating or tirelessly working as a teacher and champion of others, Parent is, by all accounts, a true force of nature.

“Her whole life is devoted to furthering everybody’s existence, whoever is in her orbit,” Halasa said. “She’s like the Rock of Gibraltar for really everybody, the whole skating community.”

Parent skates because she loves it, of course. But her passion clearly expands far beyond the ice: The point, to her, is helping the people around her.

“You see,” she said, “for me, it’s not about what [the New York figure skating community] has done for me. It’s what I can do for them.”

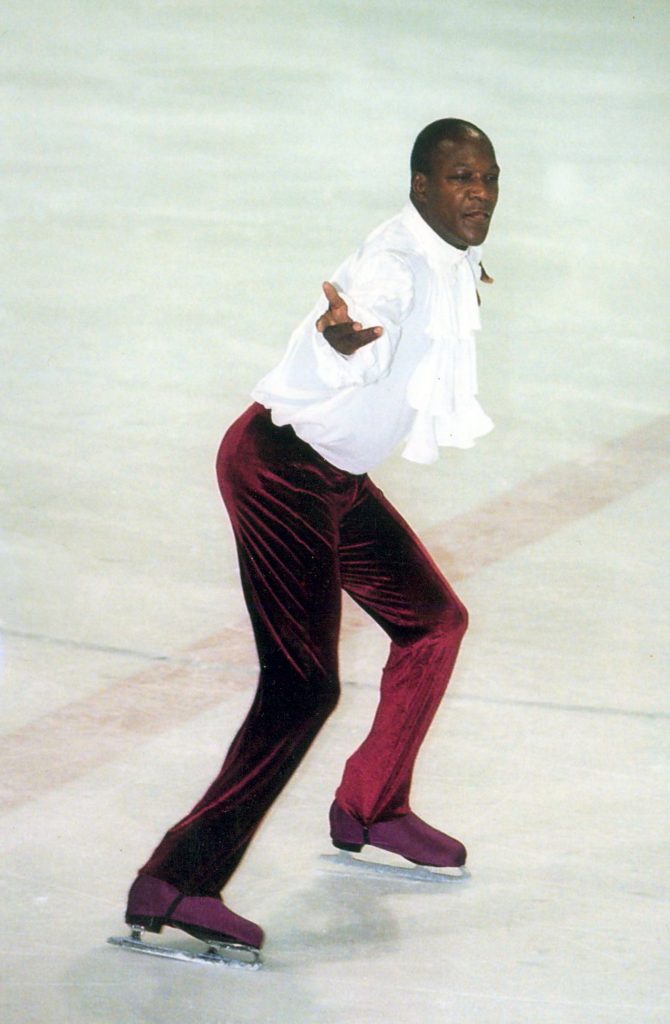

The wonderful life of Wade Corbett

Wade Corbett does not like winter. He prefers to stay inside and watch the snow from his window. He didn’t grow up dreaming of figure eights and training on ice rinks. In fact, he never particularly considered figure skating as a possible passion or career path, instead focusing solely on dance. So how, then, did he become one of the most respected, most senior members of the figure skating community, both in New York and beyond?

Corbett spent years immersed in the world of classical dance, training, performing, and touring. He even has an A.S.S. in dance and theater and performed with the International School of Ballet at Carnegie Hall for more than a decade. But as he grew into his mid-20s, he realized that the fickle nature of dance jobs can make it difficult to find steady income — and you can’t tour your entire life.

So, one winter, when he was around 25, he found himself not doing much of anything — “just plugging along,” as he put it. But then, his “body started talking” to him.

“You’re always taught to listen to your body,” Corbett explained. And his body was telling him it needed to be doing something. Somewhat fatefully, a friend from Canada happened to be visiting and, upon seeing Wade’s conundrum and hoping to drag him out of his winter funk (or at least out of his home), said, “Well, let’s go ice skating,” and took him to Sky Rink.

But Corbett’s first skating excursion ended up with him flat — literally — against it.

“I saw someone do an arabesque and thought, ‘Let me try that!’” he recounted. “Well, I tried it and didn’t know about the toe pick at the front of the blade, so I did a faceplant.”

This did not deter him, however. A few weeks later, he returned to Sky Rink, and something incredible happened.

“I started skating and…that was it,” he said. “I just fell in love with it. I’ve been doing it now for over 40 years.”

People would come up to him after seeing him skate and ask if he could coach their children, or choreograph a number for them. Without even intending to at first, Corbett became a fixture of the New York figure skating community, not only for his abilities and amazing performances, but for his teaching and choreography, as well.

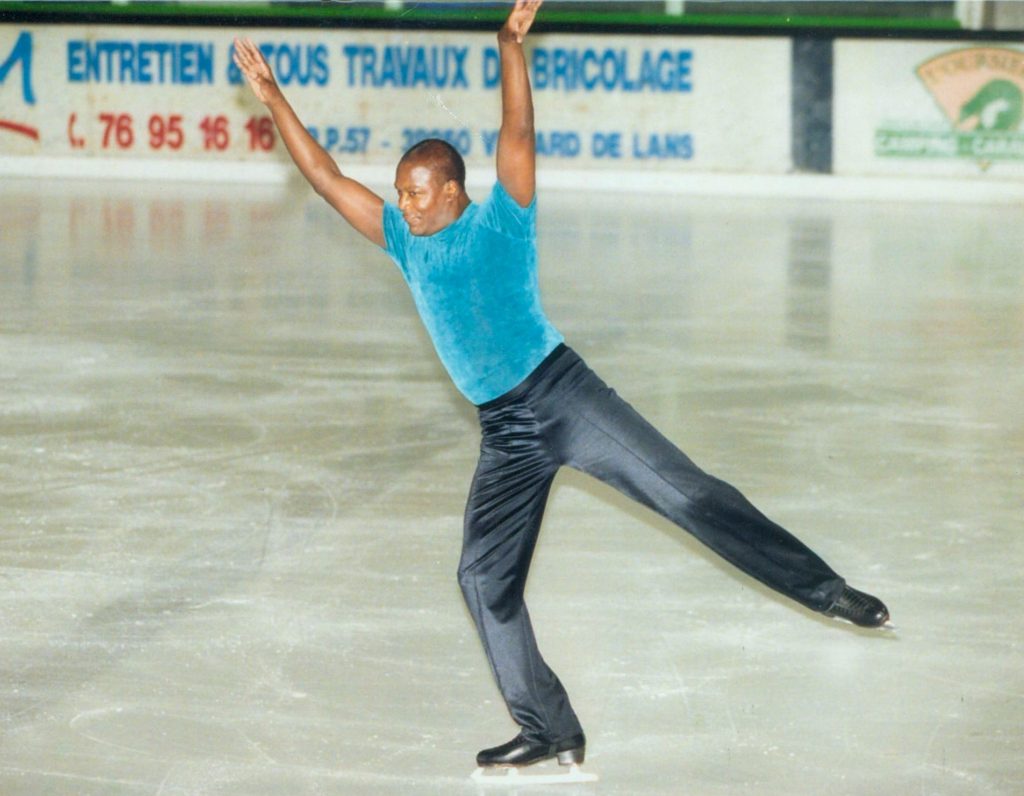

He joined the Ice Theatre of New York in 1984, worked with personal role models, like John Curry, and won a gold medal at the very first Gay Games to include skating as an event in 1994. He even became director of the skating school at Sky Rink, the very rink where he had face-planted so many years earlier.

Fellow Sky Rink skating teacher Halasa has very fond memories of Corbett’s generosity and energetic spirit.

“He was really an amazing boss,” she said, noting that the two of them are still very good friends to this day.

Corbett had personal investment in each student, encouraging them to follow their own passions. His philosophy regarding teaching skating became Halasa’s, as well.

“If there’s a desire to skate, [he really told us to] pay attention to that and develop that. He’s amazing, really.”

To see someone who started so late — at age 25 —gain such success in the world of figure skating is nothing short of remarkable. Twenty-five feels late to start any sport, but within the world of competitive skating, in particular, there is an unofficial consensus on the age one needs to begin training by: Olympic skaters start training at 3 or 4, most skaters around 6 to 9, and the “late bloomers” around age 14, although they’re already too old to realistically skate competitively.

Given those numbers, it is nearly unheard of for a competitive, professional skater to begin at the age of 25. But there Corbett was, gliding his way through the world of figure skating with ease, finesse and grace.

“Everybody knows Wade,” Halasa said, citing his long-standing involvement with and performances at the Gay Games as one of his claims to fame. “I mean, if you’re a figure skater, all over the world, people know Wade.”

Part of Corbett’s unusually natural proficiency at skating came from his long experience with dance.

“I skated as a dancer,” he said. “My arms, my movement — all that was a dancer. Skaters emulate dancers already, so I had the best of both worlds. And that, to me, is just a beauty. I mean, skating and holding an edge and just doing spirals and spread-eagles — it’s just so beautiful. I fell in love with it.”

He talks with great passion about the unique nature of movement on the ice: Unlike dance, in which any movement must always start and stop, where your leg will raise but must soon come down in order to continue the routine, skating allows for continuous movement and the ability to keep going for what feels like forever.

“I could eat my lunch all day in a spiral if I wanted to,” Corbett laughed.

His passion for the act of skating itself is matched only by his passion for making that experience possible for others. Out of everything he’s done and achieved in his long, illustrious career, Corbett said that one of the things he’s most proud of is his bringing minority children into skating.

“I became the director of Riverbank State Park,” he recalled. “I opened the first skating school up there. I had minority children coming to skating school, and I was so proud of that. That was for the kids in Harlem, not for money or anything else.”

He never let the lack of other Black skaters in the sport deter him.

“I was always aware there were no other Black people on the ice, but I just kept skating, doing my thing,” he said.

And he hopes that his presence, as well as that of other Black skaters, shows other people of color, children and up, that skating is something possible for them, too.

Corbett takes immense pride in the successes of his younger students, many of whom have gone on to careers in the skating world; they include professional skaters, skating physical therapists, even the executive vice president of Chelsea Piers, Sky Rink’s current location. But his greatest joy comes from teaching adults. Because he himself began skating so late, he feels a visceral, almost vicarious pride upon seeing an adult skater nail a spread-eagle, or a three turn, or any other move they never would have believed themselves capable of doing.

“When an adult learns something new, it’s an epiphany — like, ‘Oh, my God, I didn’t think I could do this!’ I want to cry with them. It’s so amazing, seriously.”

He has had adult students who go on to figure skate for the rest of their lives, some even doing so competitively, or involving themselves in skating in other ways, such as becoming an official judge or coaching students themselves. Corbett loves working with adults so much that, were he able to return to the rink — if his body allows him, he said — he would work solely with them going forward.

After skating — and winning for his category — in the 2018 Gay Games at the age of 70, Corbett has finally stepped away from the rink.

“I could still go up and cut a rug on the ice if I really wanted to,” he said. “But I’m getting older.”

Even so, he remains an integral part of the skating community: He’s an official skating competition announcer at Sky Rink, assists other coaches in training and developing ideas for choreography, and keeps figure skating in his life as much as possible. He plans to go to the next Gay Games, even if he’ll be attending as a spectator rather than competing.

“I haven’t missed a Gay Games since it came to New York in 1994,” he noted, adding he doesn’t plan on starting now.

Corbett’s love for skating and the Gay Games goes beyond the rink, however. And skating is more than just a sport to him: “It’s a family,” he said. “In the locker rooms, everyone’s kissing and hugging. It’s not cutthroat like competition can be. I cheer for my competitors and they cheer for me and we all go have cocktails after the competition.”

Now, looking back at his life and his career in figure skating, Corbett said he doesn’t regret a thing.

“Once you have a dream — and I did, and I’m lucky I discovered the dream before it floated away from me — sure, you give up things, but you gain so much,” he said. “And that’s that’s the only way I can look at it.

“I’ve had a wonderful life. I’ve had a wonderful life — and that’s not from the movie.”

Interesting, well-written article!