BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | An 18th-century tombstone unearthed during the Washington Square Park renovation 14 years ago has finally found a new resting place — in the window of the park’s field house.

A ceremony outside the Parks Department building was held on the morning of Fri., Sept. 22 — the 224th anniversary of the death of James Jackson, the man whose name graces the stone.

An Irish immigrant from County Kildare, Jackson died of yellow fever at age 28. He had only been in America about a year. At the time of his death in 1799, he lived at 19 East George St., on what is today Market Street just south of the Manhattan Bridge in the Two Bridges neighborhood.

Jackson was a volunteer night watchman — basically, a police officer.

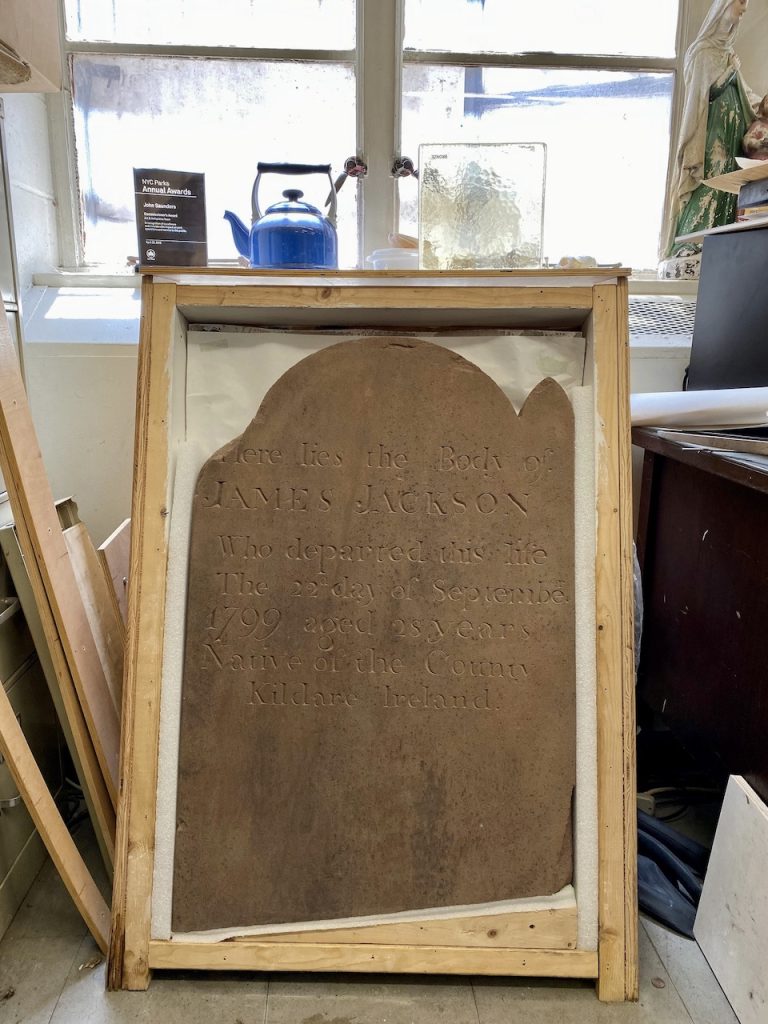

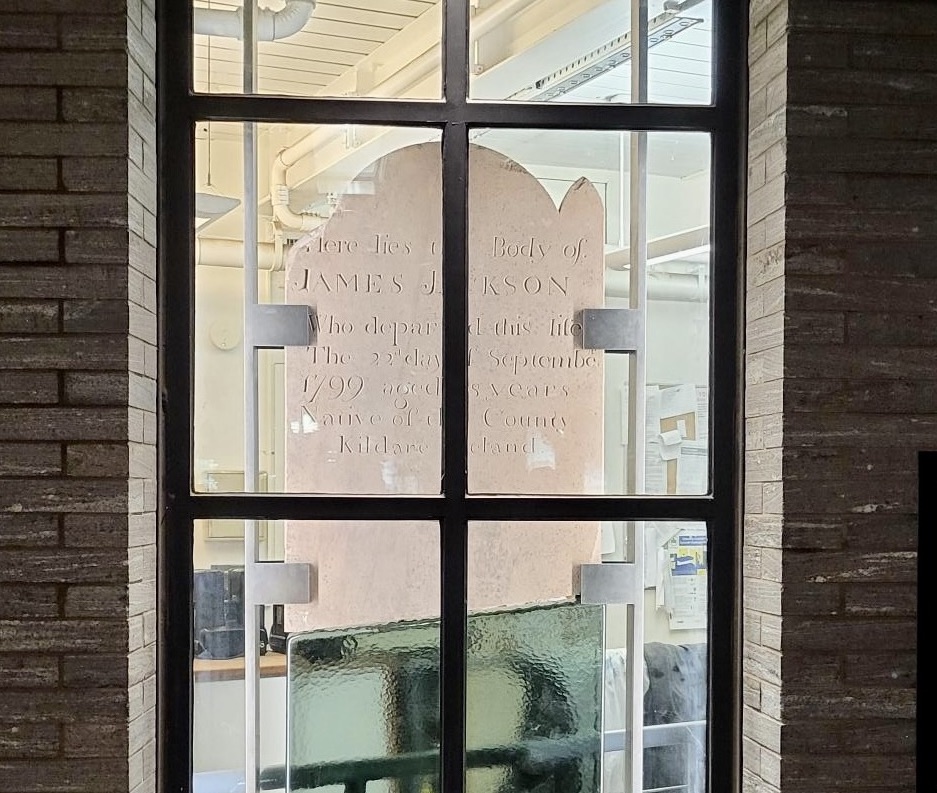

Carved from brownstone, the headstone was found buried a foot and a half belowground in 2009, during archaeological testing before the renovation of the park’s Sullivan Street entrance. It now rests, not far from where it was excavated, in a bay window visible to the public in the park house, with an explanatory sign next to it.

In 1797, the future park first started being used as New York City’s first potter’s field — a burial ground for the indigent. A month before Jackson’s death amid the yellow fever outbreak, the city decreed that all the disease’s victims also be buried in the potter’s field, since it was believed yellow fever was infectious. In fact, yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes.

Some estimates say up to 10,000 bodies were interred in the potter’s field. In 1825, the burial ground was converted to a parade ground — then, in 1827, to a park.

The potter’s field burials were not marked by headstones, so how Jackson’s wound up there remains a mystery — though there are theories.

Joan Geismar, who back in 2009 was a consulting archaeologist for Parks, did the initial research. She then passed the baton to Marion Casey, a professor of Irish studies at New York University, who did further research in Ireland, trying to find out more about mystery man James Jackson. Not making things easier, it’s a common name in that part of Ireland.

Geismar believes Jackson was originally buried — with the headstone — in the potter’s field. However, Casey’s theory is that a wealthy Irish-born property owner — retired Captain Robert Richard Randall, who had an estate stretching north from what is today Washington Square North — was able to get Jackson buried on his property. Later on, when the city cut Eighth Street through Randall’s estate and the north side of the park was developed in 1831, Casey’s theory goes, Jackson’s headstone was moved to the park, while his body was moved to a vault at St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery.

Human remains that were found near the headstone were determined not to be Jackson’s.

Casey noted that the immigrant — whom she believes was Protestant — could well have been part of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, when the United Irishmen, who were both Catholic and Protestant, rose up against British rule. But the revolt was quickly quashed. Instead of death or prison, some rebels had the option of emigrating to America.

Geismar believes Jackson had four children, but Casey is not so sure about that.

The professor’s thought is that Captain Randall personally paid for the headstone.

“He’s not a pauper,” she said of Jackson, “but I don’t think a watchman’s salary would have been able to afford that.”

Randall himself was buried on his estate in 1801, she noted.

Jonathan Kuhn, Parks’ director of Art & Antiquities, was the ceremony’s emcee.

Speaking after the dedication, he noted that, because the headstone was buried, it actually is in better shape than similar ones of its era — since it was protected later on from the corrosive effects of acid rain.

“It wasn’t expected” to find the stone, he said, “given how many times the park has been rebuilt.”

In his remarks at the ceremony, Kuhn called Washington Square “the most intensively used park in the world. It’s a park, too, of many historic layers,” he noted.

Kuhn recalled the people who once inhabited the area — the Lenape, whose Sapokanikan village was nearby when Europeans settled the borough’s southern end; freed African slaves Manuel Trumpeter and Manuel Groot, to whom the Dutch colonial government gave land grants, who also lived nearby; wealthy merchants who developed the area in the late 19th century — followed by other kinds of denizens, the bohemians of the early 20th century and then the Beatniks.

Anthony Perez, the Manhattan borough Parks commissioner, reflected on “the arc of time and the changing use of public space.”

“Two hundred years ago, it was a potter’s field during yellow fever,” he said. “Now it was an open space to get outside during COVID and showed the value of public space. Who knows what will be there in 200 years?”

Perez also complimented Will Morrison, the park’s administrator, saying, “He’s done a great job with this park during his tenure.”

Helena Nolan, the Irish consul general, thanked everyone involved for the “dignity” with which Jackson’s headstone had been treated.

Sarah Carroll, the chairperson of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, praised her predecessor, Robert Tierney, for having had a proactive plan in place to protect historical artifacts when, as expected, they cropped up in the park during the renovation.

Andrew Berman, director of Village Preservation, acknowledged Kuhn’s efforts in protecting the piece of history.

“They’re fragile, our public spaces and our history,” he said. “Without a lot of work, they are paved over, they are forgotten.”

Coucilmember Christopher Marte liked that it was a working-class person who was being honored.

“It’s so important to remember our history and know where we come from, remember the working people that built this city,” he said.

Susan Kent, the chairperson of Community Board 2, also spoke.

There was singing at the beginning and end of the event, by Guen Donohue and Clare Martin.

Summing up Jackson’s brief life, Casey said, “He was a young man from a part of Ireland convulsed by rebellion in 1798, who died in a city ravaged by a deadly epidemic in 1799.”

To the Parks Department’s Kuhn, she gratefully added, “Thank you for never forgetting or losing this stone.”

Be First to Comment