As Bob Dylan turns 80, Liz Thomson recalls his early years in the clubs of Greenwich Village and Robert Shelton, the New York Times critic whose perceptive review changed the course of music history. Shelton’s definitive 1986 biography, 20 years in the making, “Bob Dylan: No Direction Home,” was reissued today in a new, lavishly illustrated, abridged version.

BY LIZ THOMSON | Those were the days… .

Sixty years ago this September, a New York Times review of a scrawny kid from the American Midwest playing a Greenwich Village cabaret changed forever the course of popular music.

The kid was Bob Dylan, and the critic was the late Robert Shelton, who, in 1959, had witnessed the Newport Folk Festival debut of Joan Baez, rhapsodising about her “achingly pure soprano.”

Shelton would write about many more debut performances, including Jose Feliciano, Joni Mitchell, Janis Joplin, Janis Ian and Frank Zappa, at clubs whose very names long ago became legend — the Café Wha?, the Gaslight, the Commons, the Village Gate… .

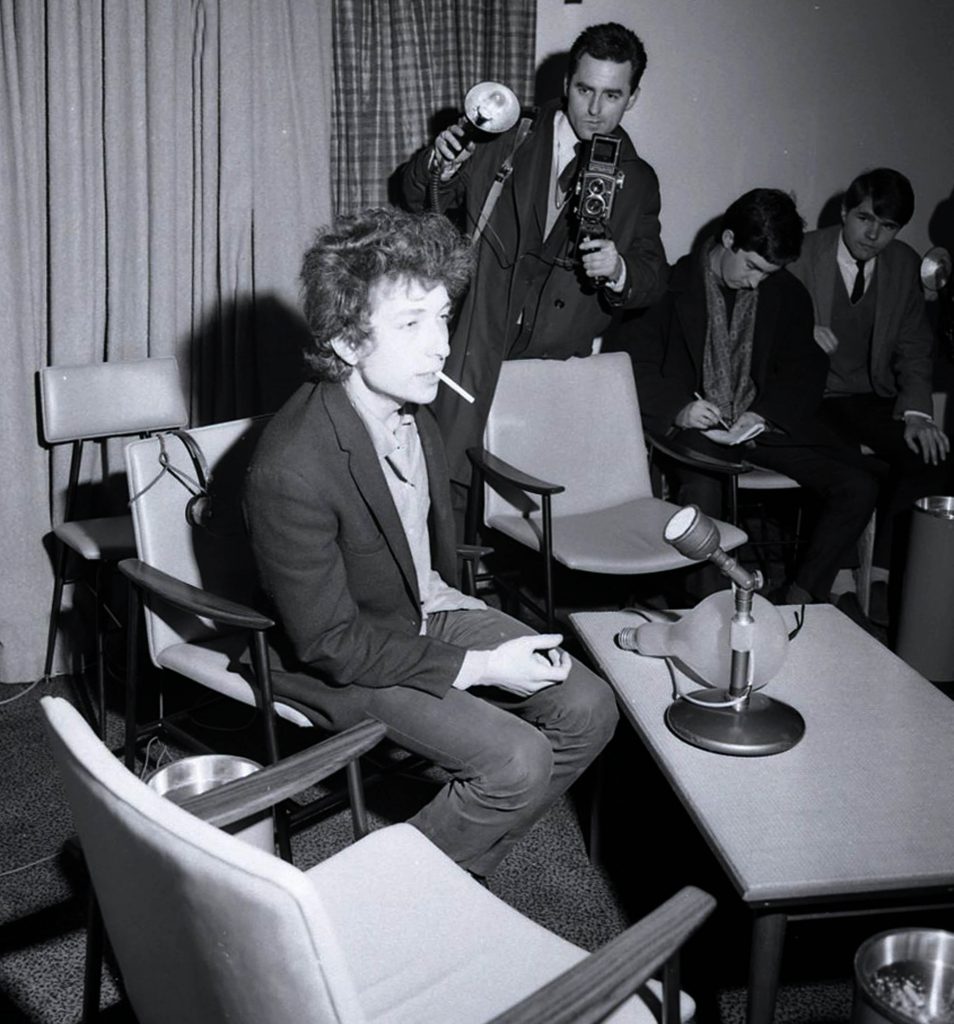

That night at Gerde’s, then at 11 W. Fourth St. in the heart of Greenwich Village, Shelton had expected to focus on the headliners, a bluegrass trio named the Greenbriar Boys. In the end, most of his review, plus the photo, was devoted to the supporting act.

On Sept. 29, 1961, under the four-column headline “Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk-Song Stylist,” Shelton wrote that, “A bright new face in folk music is appearing at Gerde’s Folk City. Although only 20 years old, Bob Dylan is one of the most distinctive stylists to play a Manhattan cabaret in months.” Saying Dylan resembled “a cross between a choirboy and a beatnik,” Shelton wrote that his work bore “the mark of originality and inspiration, all the more noteworthy for his youth.” The article concluded, “Mr Dylan is vague about his birthplace and his antecedents but it matters less where he has been than where he is going, and that would seem to be straight up.”

Unsurprisingly, the review caused quite a stir and, within a couple of weeks, Dylan had been offered a contract with Columbia Records. Suze Rotolo, the girlfriend pictured on the sleeve of his 1963 album “Freewheelin’” walking arm-in-arm with the singer through the Jones St. slush, recalled the time as “over-the-top exciting. We got the early edition of the paper late at night at the newspaper kiosk on Sheridan Square, and went across the street to an all-night deli to read it,” she said. “Then we went back and bought more copies… . Robert Shelton had been around the clubs and bars for ages, seeing every new and old performer, but he’d never written a review quite like the one he wrote for Bobby… .”

Dylan was not yet 20, a high school rock ’n’ roller who’d succumbed to folk music during his brief career at the University of Minnesota — the urban folk revival was sweeping America, campuses were in thrall. He’d hitchhiked to New York with the aim of meeting Woody Guthrie, composer of “This Land is Your Land.” Huntington’s chorea had ravaged Guthrie’s body, but Dylan was unfazed, singing to him and writing his “Song to Woody,” the only original song on his debut album.

Dylan arrived in the city in January 1961, waving goodbye to his ride where the George Washington Bridge meets Manhattan Island and taking the subway downtown to Greenwich Village, “a Coney Island of the mind” (Lawrence Ferlinghetti) where everything started…except Prohibition.

The Village in the 1960s was “a scene,” the Beats and the folkies wandering its crooked streets. It was a place of low rent and high art, where those living alternative lives were not just tolerated but encouraged. Before the Civil Rights Act, before Stonewall, blacks and whites could mingle without fear, gays cohabit. The locus of this perennial bohemia was of course the crossroads of MacDougal and Bleecker Sts.

Long before Bob Dylan came to town, Robert Shelton was part of that scene, his apartment at 191 Waverly Place, between Sixth and Seventh Aves, equidistant between Gerde’s and the White Horse Tavern, the longshoremen’s bar where Dylan Thomas took his last drink and where the Clancy Brothers’ rebel songs raised the roof.

In retrospect, it’s extraordinary how much space the New York Times devoted to young unknowns playing on Downtown’s makeshift stages, its readers invited to follow Shelton into smoke-filled bars and coffeehouses, much as they followed his classical counterpart, the great Harold C Schonberg, into the Uptown splendor of Carnegie Hall and the Met.

In those far-off analog days, of course, the Times (because much its content was syndicated) was the closest the United States came to a national newspaper: Shelton was writing not just for Manhattanites, nor even simply for those across the five boroughs – but for general readers and record buyers across the country. Singer Judy Collins told me that Shelton was a critic “with the intelligence and perception and ability to get the fact that something rare and wonderful was happening in the world of music and social consciousness” and he wrote about it with “a crisp and unique clarity.”

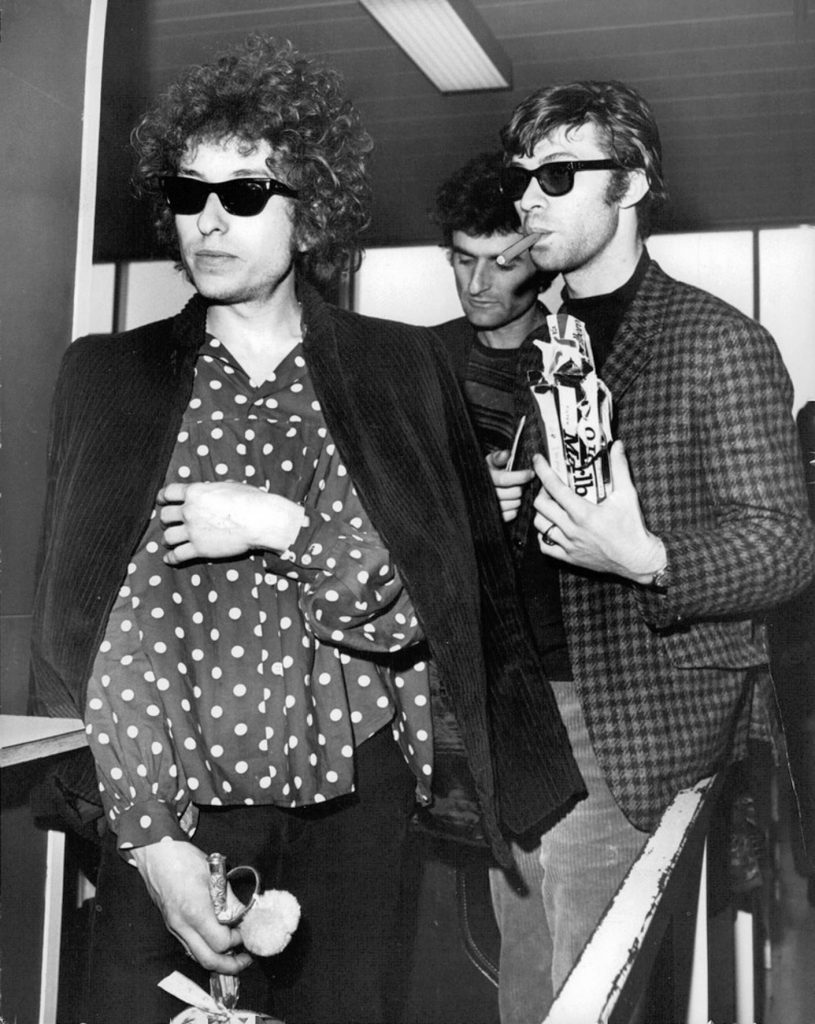

For a few heady years in the Village, Shelton and Dylan hung out, often with their respective girlfriends — Suze Rotolo and Joan Baez in Dylan’s case. The friendship did not prevent Shelton from being critical, in person and in print, but he was fair-minded and understood from the moment he first heard him perform that Dylan was a talent like no other. The biography he proposed over dinner on New Year’s Eve 1965 was never intended as a potboiler — but neither was it meant to take 20 years to complete. But Shelton talked to everyone.

Shelton was there, a witness to all the crucial moments in Dylan’s career. At Newport ’63, when Dylan was anointed “crown prince” to Baez’s “folk queen,” and at the celebrated Philharmonic Hall concert on Halloween 1964. At Newport ’65 when Dylan went electric. On the pivotal 1966 tour with the Hawks — the long, candid interview aboard Dylan’s private jet is at the book’s heart. At the Woody Guthrie memorial in 1968, the Isle of Wight in 1969. They chatted for hours in New York in 1971, during Dylan’s long public withdrawal, and talked long into the London night during the 1978 tour.

Shelton was given unique access to many of those closest to Dylan, including parents Abe and Beatty, whom no other journalist ever interviewed — when news broke of Dylan’s motorcycle spill, it was Shelton they rang. He spoke to childhood friends from Hibbing, including Echo Helstrom, the “Girl from the North Country,” and fellow students and friends from Minneapolis. He talked to fellow musicians, including Baez, Mary Travers, Peter Yarrow, Jack Elliott and Pete Seeger, Johnny Cash, Dave van Ronk, Richard Fariña and Phil Ochs. To his manager, Albert Grossman; to his first producer, John Hammond; and to would-be Dylan producer Phil Spector, interviewed during the “River Deep, Mountain High” sessions. So many of those witnesses are no longer with us, yet their testimony lives on, thanks to the assiduous work of Robert Shelton.

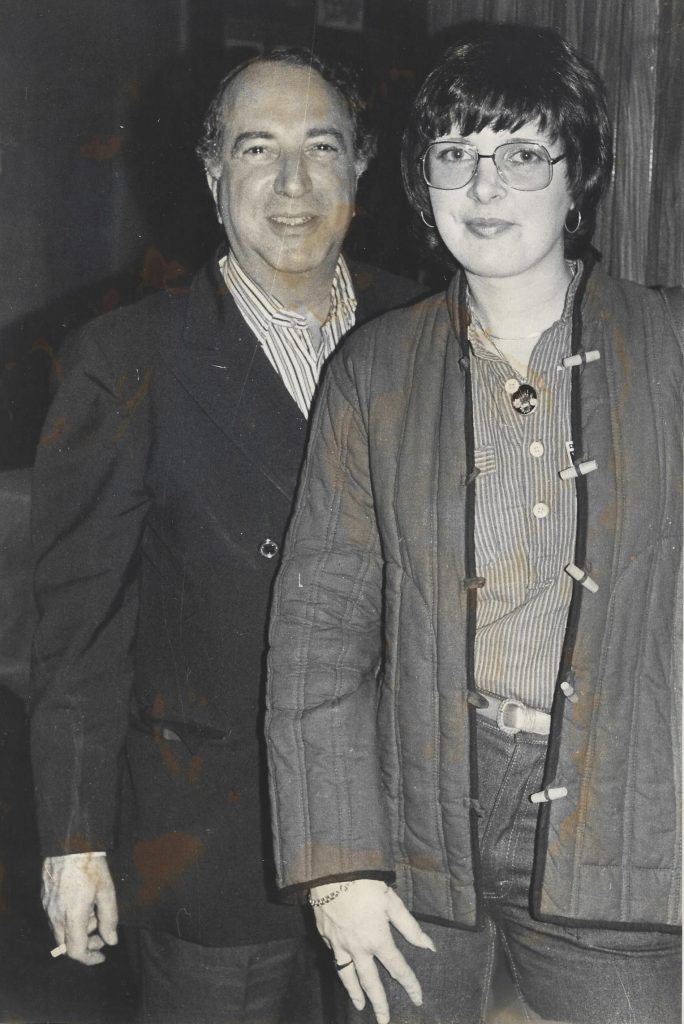

When I first met Robert in 1979, I was a new-minted music grad and memories of my first-ever Dylan concerts were vivid in my mind’s eye and ear. The critic was then engaged in a titanic editorial battle over taste and aesthetics. His aim was always a serious biography that placed Dylan among such 20th-century shapeshifters as Shaw, Picasso, Welles and Brando but his publisher wanted gossip. At an age when my high school classmates had been screaming for Donny and David (Osmond and Cassidy), I was already obsessed with Dylan and Baez. (Joan, about whom I wrote in “The Last Leaf,” was the Venn diagram through which I explored American music and the nation’s 20th-century psychodrama.)

By the time of our chance encounter at a Dylan conference, Robert had been living in London for a decade, writing his biography without anyone peering over his shoulder. “No Direction Home” was eventually published in 1986 and he always said his lifetime’s work had been “abridged over troubled waters.” He hoped to revisit the book but died suddenly in 1995, aged 69. The New York Times obit said he had been both “catalyst and chronicler of the 1960s folk boom,” while the Grammy-garlanded Janis Ian, whom Robert had brought to the attention of Leonard Bernstein, noted that Shelton had been “the father of rock journalism.”

Fifteen years later, I restored Robert’s original manuscript, and his book, in all its vivid, pointillist detail, was finally published in the form he’d intended for Dylan’s 70th birthday. The launch party was at the Washington Square Hotel, which Dylan and Baez and so many others had of course known as the Hotel Earle. But its 225,000 words made it a book for dedicated Dylanistas.

This new 80th birthday edition, lavishly illustrated with 150 photos, is hewn from that text. More approachable, it enables a new generation of readers to follow Bob Dylan — the original punk, who put poetry on the jukebox — “down the foggy ruins of time” with Robert Shelton as their guide. It’s a beguiling and atmospheric eyewitness account — the only one.

It was during the painstaking 2011 restoration of “No Direction Home” that the idea for a festival celebrating Greenwich Village first popped into my mind. How extraordinary it was that so much happened in so many ramshackle clubs around Washington Square! I wish I could have been there! So the original idea was for a music festival. But crazy as it may have been, the idea developed into a celebration of the Village itself.

There was “music in the cafes at night and revolution in the air” long before Bob Dylan hit town — remember, Marcel Duchamp and the arch conspirators spent that cold snowy night drinking red wine atop the Washington Square Arch in January 1917, and as dawn broke declared that the Village would secede from the United States! Over the last few years, many people probably wished it had!

“Bob Dylan: No Direction Home,” by Robert Shelton, illustrated and with a new foreword and afterword by Elizabeth Thomson, was published by Sterling Publishing on May 24, 2021. The Village Trip 2021 festival will take place from Sept. 18 to Sept. 26, with a free concert in Washington Square Park on Sat., Sept. 25. For more information, or to donate, go to www.TheVillageTrip.com.

Has the driver who dropped Dylan off at the GW Bridge ever realized what he did and been interviewed?