BY THE VILLAGE SUN | An all mask-free crowd gathered on Gansevoort Peninsula recently to celebrate the dedication of David Hammons’s colossal “Day’s End” public artwork.

Attendees at the May 17 event had to show proof of vaccination or a recent negative COVID test or, right before the event, score a negative on a rapid-result test at the Whitney Museum of American Art across the street.

The massive yet ethereal $18 million sculpture, which was installed in April, was commissioned by the Whitney. All the funds went to the piece’s fabrication and installation.

The enigmatic “ghostly” sculpture is an homage to Gordon Matta-Clark’s 1975 work of the same name. In an “intervention,” Matta-Clark cut five monumental openings into the abandoned pier shed on Pier 52, which formerly sat off the south edge of Gansevoort.

Using slender steel pipes, Hammons’s artwork traces the exact dimensions and location of the original Pier 52 shed, measuring 52 feet high at its peak, 325 feet long and 65 feet wide. The piece should last 100 years, according to Hammons.

The dedication event included a “land acknowledgement” by George Stonefish, a descendant of the Lenape, the indigenous people who originally inhabited Manhattan.

In a similar vein, Whitney Director Adam Weinberg recalled the spot’s rich, many-layered history. He quoted from the great American author Herman Melville, who, he noted, spent the last 20 years of his life working as a customs inspector on Gansevoort Peninsula while penning “Billy Budd.”

In “Moby Dick,” the narrator Ishmael says, “Yes, as everyone knows, meditation and water are wedded forever.”

Hammons’s own meditations on the Hudson resulted in “Day’s End,” Weinberg said, noting, “The river spoke to him and this is his gift to the river and the city.”

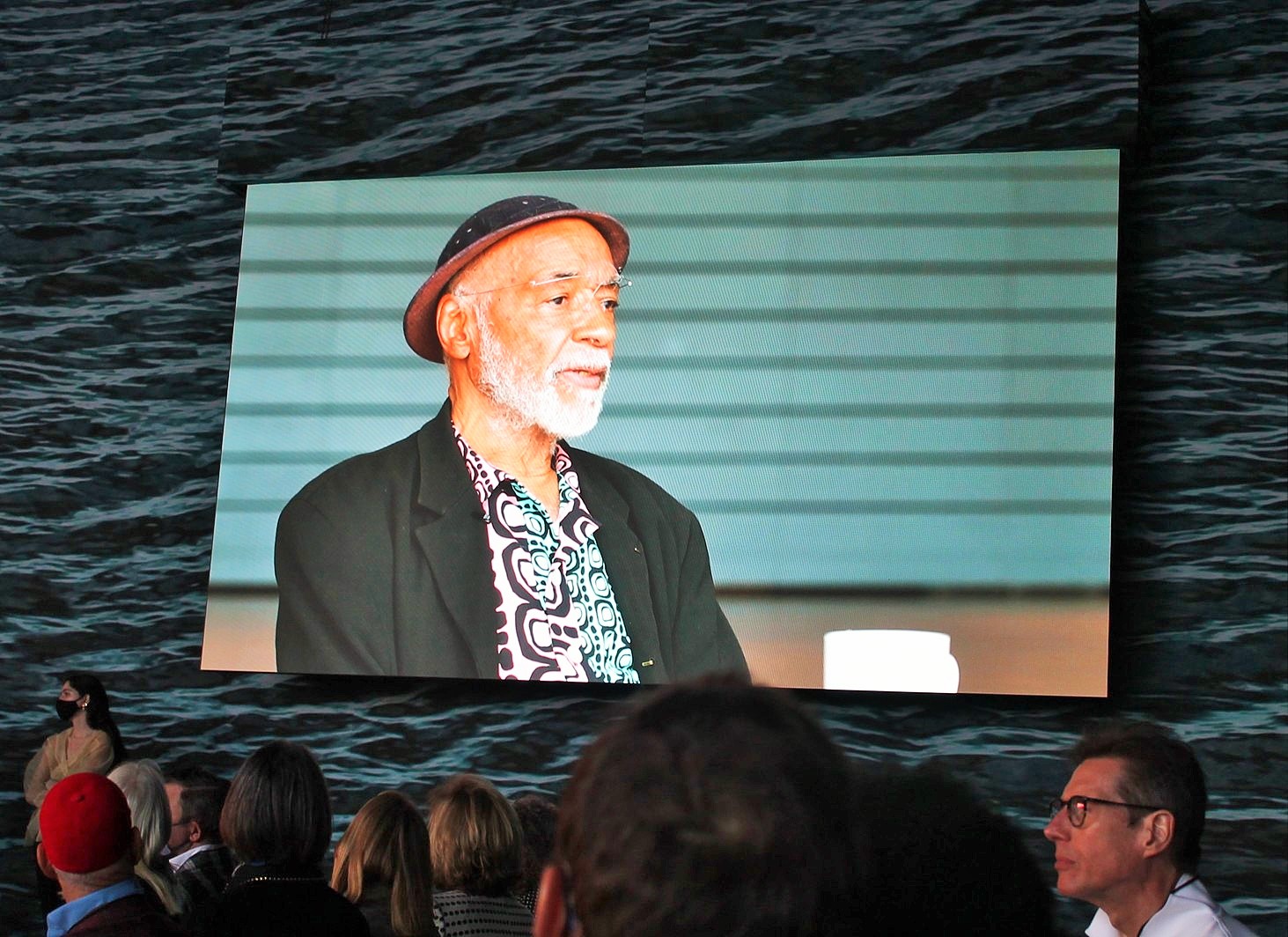

The artist did not appear in person at the dedication, but rather in a prerecorded video in conversation with Weinberg that was projected on the wall of the venue. A ski chalet-like temporary structure open on two sides was constructed for the occasion.

In the video, Hammons said of “Day’s End” that he “looks at it as a statue” and that, as well as “history,” the piece also signifies “mystery.”

The artwork and Gansevoort are both in the 4.5-mile-long Hudson River Park. The park’s governing state-city authority, the Hudson River Park Trust, is currently building a park on Gansevoort, complete with a “beach” and a playing field.

Vicki Been, the chairperson of the Trust’s board of directors, pledged, “We will make sure that [the Gansevoort] park does this incredible piece of art justice.”

She noted that during the pandemic, “parks became our living room, dining room…and now they are our museum.”

Abstract artist Julie Mehretu, who currently has an exhibit of 70 paintings and works on paper on view at the Whitney through August, called Hammons’s art thoroughly iconoclastic. Hammons’s work, she said, exposes “the failures of modernism, the failures of objecthood” and critiques “racist and cultural assumptions.”

If Hammons looks at his minimalist installation “as a statue,” he needs to consult a dictionary. Mine says a statue is a “sculpture of a human or animal figure.”