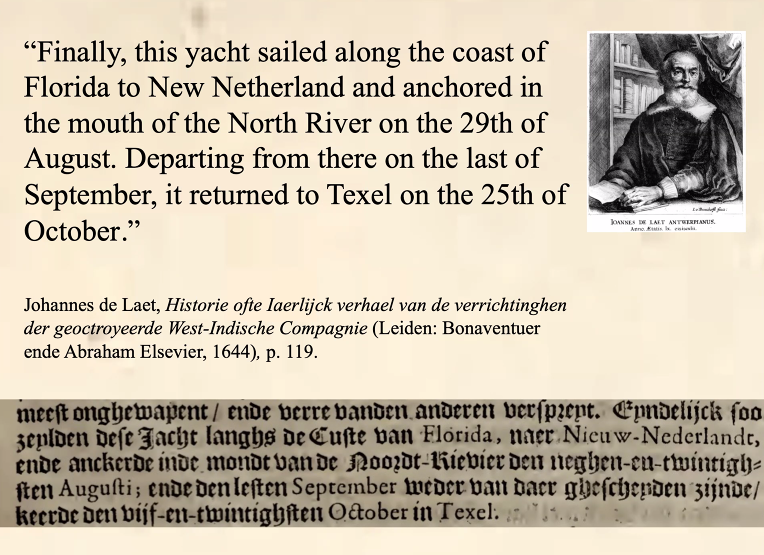

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | It’s an ignominious and dark date, but a Dutch scholar says he has established the exact day and year when the first enslaved Africans arrived at Manhattan Island.

Dr. Jaap Jacobs, a professor at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and a specialist in the history of the Dutch Republic and its colonies, has reached the conclusion as part of his research for a book he is penning about Petrus Stuyvesant a.k.a. Peter Stuyvesant.

Jacobs has been periodically sharing some of his findings with St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, beneath which Stuyvesant is buried. The East Village church has been engaged in a reckoning over its early congregants’ ownership of slaves.

According to Jacobs, 22 Africans were first brought to New Amsterdam, at the southern end of present-day Manhattan, 394 years ago on Aug. 29, 1627. They were aboard a fairly small ship called the Bruinvis (“the porpoise”), which had sailed from Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

It was only the previous year that the Dutch claimed to have purchased Manhattan from the Native Lenape for 60 guilders, the equivalent of more than $1,000 today.

As Jacobs tells it, the Africans had been among 225 aboard a Portuguese ship that was likely bound for Cartagena and sugar plantations in New Spain when it was waylaid by a fleet of five smaller Dutch privateer ships. The Bruinvis took only 22 of the slaves.

Mayken was onboard

The Africans were likely from Angola, according to Jacobs’s research. He also believes that among them was a woman named Mayken van Angola, who in her older years, after winning her freedom, became a housekeeper — possibly only part-time — for Stuyvesant, the director general of New Netherland. Jacobs said he has confirmed from original source materials that Mayken was on Manhattan Island in 1628, the year after the Bruinvis’s arrival.

As previously reported by The Village Sun, Mayken, in fact, also may well lie buried with the colonial leader in the sealed Stuyvesant family vault beneath St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery in the East Village, according to the scholar.

The first person of African descent to settle on Manhattan reportedly was Juan Rodriguez, who was half-Portuguese and half-West African and grew up in Santo Domingo on Hispaniola (present-day Dominican Republic). In 1613, he manned a Dutch trading post in Lower Manhattan and married into the local Lenape community, or at least that’s the accepted narrative. But Jacobs said it’s not clear what Rodriguez’s “capacity” was or if he actually set foot in Manhattan or somewhere else in the area.

In short, Jacobs is taking nothing for granted in his detailed research and always goes to the original source material — period letters and documents. His research basically involves, as he put it, “connecting the dots, as it were — but do it carefully, carefully.”

A hard look at Stuyvesant and Dutch slavery

As part of his Stuyvesant book, Jacobs is trying to define more exactly how many slaves Stuyvesant personally owned and also the general nature of slavery in New Netherland, the Dutch colony of which New Amsterdam was the capital and largest part of.

“New Netherland was never a plantation system,” Jacobs said. Rather, Africans were made to do “manual labor, helping build the fort, harvesting, cutting down trees, burning lime, splitting wood.”

In 1635, five Blacks from New Amsterdam turned up back in the Netherlands demanding their wages, something “regular company servants” — as in, indentured servants — of the Dutch West India Company would do, he noted. A “proxy” could have been empowered to collect their pay for them, but the five Blacks might have felt they needed to show up in person to guarantee getting paid.

“‘Company servant’ means a worker in servitude to the company,” Jacobs explained. “You sign up for five years, then go back [to the Dutch Republic] to collect your money.”

‘Half-freedom’

The Dutch also had something called “half-freedom,” which was introduced in 1644, but which Jacobs said could better be called “half-slavery.” It had three conditions, as he outlined in his 2009 book on Jacob Leisler, a heroic Dutch colonist who was killed by the conquering British: “The first condition [for half-freedom] was that, per person, they had to pay to the [Dutch West India] Company 30 schepels [bushels] of maize, grain or other agricultural products annually, together with one fat pig at a value of 20 guilders. This was a lifelong obligation, and in the case of default the Blacks would relapse into slavery. The second condition was that, if their services were called for, they would be obliged to serve the W.I.C. on normal terms of payment. The third condition was the most controversial: Both their existing children and any children as yet unborn would ‘remain bound and obligated to serve the honorable West India Company as lijffeygenen [serfs].’”

As for the model of slavery employed by the Dutch, he said it was more “lenient” — that they did not want be “as barbaric as the Spanish and Portuguese.” Yet there was no question the slaves were on the bottom of the pecking order, beneath company servants and free Blacks.

At the same time, Dutch involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade grew, to the point where, between the 1630s and 1670s, they may have handled 25 percent to 30 percent of it, Jacobs said.

“They began to emulate the slavery that they saw in Brazil by the Spanish and Portuguese,” he said. “This was a very gradual moral and legal descent from not allowing it, to allowing it.”

According to New Amsterdam’s 1665 tax list, 12 percent of the residents were slaveholders.

Who else is in the vault?

As for exactly who is buried in the Stuyvesant vault under St. Mark’s, Augustus Van Horne Stuyvesant Sr. — a descendant who remodeled the vault’s entrance and installed a marble catacomb in the early 20th century — claimed there were more than 80 individuals.

“That can’t all be family members,” Jacobs asserted.

Augustus Van Horne Stuyvesant Jr., a reclusive bachelor and Peter Stuyvesant’s last direct descendant, died in 1953 and was buried in the family crypt. A few months after his entombment, the vault was sealed, and remains under Stuyvesant family control.

However, Jacobs said, it’s not necessary to “dig up the vault” to establish that there must be Africans buried inside of it.

Stuyvesant as slave owner

As for how many slaves Stuyvesant himelf owned, it’s hard to pin down, he said. Past writers have given numbers but, again, Jacobs is bypassing these secondary sources and going back to original material.

“I think there were both free and enslaved Blacks living in the East Village area at the time,” he said. “Those that were enslaved were still owned by the Dutch West India Company and were not Stuyvesant’s. Although as director general of the Dutch West India Company, he could use their labor.

“There’s no doubt in my mind Stuyvesant owned a number of enslaved people,” he said. “It could have been 15. It could have been 25. I would be surprised if he did not own in that order of magnitude. We do know the Dutch West India Company hired out its slaves to people.”

The role of religion

Thoroughly coloring all of Stuyvesant’s beliefs and actions — including his relation to slavery — was his deep religious faith and conviction.

“Stuyvesant was very much an Orthodox Calvinist,” Jacobs said, “completely convinced of his own religion. Maybe more so because he had his leg shot off in the Caribbean and survived: He may have seen that as God’s favor.”

On the other hand, Jacobs said, Stuyvesant took the Peach War in 1655 as “a sign that people were drinking, fornicating and blaspheming.” The conflict was sparked when a New Amsterdam colonist killed a Lenape for picking a peach.

“He did try to Christianize his slaves,” Jacobs added. “He was relatively lenient. When a slave was purchased, he made it so you also had to purchase the wife — keep family intact.”

A Calvinist supremacist

The New Netherland director general was also known to be virulently anti-Semitic and intolerant of other Christian sects, such as Lutherans and Quakers. However, in Stuyvesant’s defense, Jacobs said the fledgling colony’s leader felt he was “keeping the community united under religion,” and so basically viewed adherents of other religions and denominations as “anarchists.”

“Stuyvesant was intolerant,” he said.

“It’s almost unimaginable how different 17th-century society was — the religion,” Jacobs said. “We fail to understand the past if we judge it on our modern precepts.

“Under a different leader, I don’t think New Amsterdam would have remained in Dutch hands for as long as it was,” he said. At the same time, Jacobs noted, “He couldn’t be a dictator. He had to answer to the Dutch West India Company.”

‘Unlikely vault will be opened’

As for the Stuyvesant vault under St. Mark’s, its mysteries may never be fully revealed.

“I think it’s unlikely that the vault will be opened while the church is still standing,” Jacobs offered.

The professor said that, due to the current day’s “contentiousness,” it’s even less likely the crypt would be unsealed. Basically, people might want to go as far as to remove bodies from the vault, he said. The future of Stuyvesant’s bronze bust in the churchyard that gazes at the vault is being debated.

“If there’s talk of removing the bust, which was put there as a symbol of Dutch-American friendship…” he said, his voice trailing off.

The two-statue solution

Jacobs reiterated his idea for a solution, which The Village Sun previously reported in the first article in this series — a new companion statue to Stuyvesant’s.

“The Dutch government could fund a statue of the first Black woman enslaved,” he said. “That could be a better way to do this than removing his bust or digging up his body.”

The statue could portray Mayken, he has said, though no picture of her exists. Meanwhile, St. Mark’s, for its part, has been exploring the idea of possibly creating some kind of monument to address its own fraught history with slavery, though no decision on a design has been made yet.

Stuyvesant’s original Dutch Reform “little chapel” that sat on the site is long gone. In 1793, his family sold the property to the Episcopal Church for $1, which then built a new house of worship on the spot.

Jacobs has been researching the Dutch Republic and its colonies for 35 years now. He wants to get it right in his upcoming book on the historical figure. He noted, for example, that unlike the way he often is today, Stuyvesant wasn’t always historically depicted in a negative light. In fact, he said, it wasn’t until the 19th century that an account of New Amsterdam first portrayed Stuyvesant as an “intolerant autocrat.”

“I’m not out to rehabilitate anybody,” Jacobs stressed. “It could well be that the impact of my research rehabilitates him — but it’s not my intention.”

A date to commemorate?

While it’s known that slavery in Virginia started earlier — sometime in late August 1619 — Jacobs feels it’s significant that he has pinned down the exact date for its start in New Amsterdam, Aug. 29, 1627.

“I think the day is more important than the year,” he contended. “Having a specific day allows us to commemorate the date. That’s not up to me, of course.”

“He did try to Christianize his slaves,” Jacobs added. “He was relatively lenient. When a slave was purchased, he made it so you also had to purchase the wife — keep family intact.”

Yes. The Dutch also did a mild type of slavery. It wasn’t as hard as in other colonies.

Typical denial attitude and condescending

position.

Indentured servitude is more complicated and began when the first ships unloaded on the island. (Not sure H. Hudson did that.) And weren’t the Lenape nomadic, so why would they care about land ownership?

Dr. Jacobs — I have a friend whose direct ancestor was in large part responsible for the Dutch enlightened age (17th century) because of his extensive liberal writings and political position, which looks to have coincided with the DEI Co and the Dutch founding of Manhattan. Is there a direct connection between the outlook and general tolerance of the Dutch, (nothwithstanding their adoption of slavery) with that enlightenment back home?

Thank you for writing about Dr. Jacobs’s research, our shared history and our divisive present.

So enlightening and thorough! The nature of early slavery, the terms and conditions, deserve thorough exploration, although nothing will make it acceptable. The fact that “servants” of the DWIC could travel back to Holland to pick up their wages is a fascinating detail! What a remarkable system, that allowed someone to collect the wages for workers, believing they would get them at the end!

Thank you for this research, and also for defining the mindset of such a different era. We can disagree, but we need to acknowledge their bias, as well as our own.

Agreed, the article perpetuates the myth of not only the concept of transactional “ownership” of land but also the transactional “ownership” of human beings. The basic concepts of the story lack the compassion and sensitivity of the recognition of our fundamental humanity.

The movement to remove statues that commemorate slavery and slave owners, like the removal of Thomas Jefferson’s statue from New York City Hall, recognizes the consequence of enslavement that still exists today. This article is somehow a pushback on this movement.

“He did try to Christianize his slaves,” Jacobs added. “He was relatively lenient. When a slave was purchased, he made it so you also had to purchase the wife — keep family intact.” The article’s tone of “benevolent enslavement” misses and ignores the reality of the harshness of the beginning of historical roots of genocide of millions of Africans by European corporations and religious institutions.

Thanks your comment but the article was not intended as a pushback against anything. And slavery was not and is not a myth — it unfortunately, tragically and cruelly has existed from time immemorial and still exists around the world today. The Bible discusses slavery. The real impetus of the article was Jaap Jacobs’s ongoing scholarship about Peter Stuyvesant and his relationship to slavery and, more specifically, Jabobs’s claim to have identified the actual date when slavery started in New Amsterdam, which is newsworthy. The article was not meant as a pushback — but as a genuine contribution to human knowledge, as a sharing of a new piece of our country’s deeply imperfect and flawed history. As Jacobs says, knowledge of the date could lead to an annual commemoration, if there is a will to do that. If not, then not. Statues with racist associations can be removed from public view. But should history actually be erased and not written about and also hidden from public view? The Village Sun is not a scholar on the history of New Amsterdam, but Jaap Jacobs is. He has spent 30-plus years studying it. The article is a report on Jacobs’s latest research, mainly his claim to have found the date that slavery started in New Amsterdam. As they say, don’t shoot the messenger.

It is always good to provide clarifications, as too often summarized statements hide the complexities lurking beneath. While the commentator is correct to point at the different conceptions of land ownership, let me point out that “ownership” is a container for many different types of land claims, either exclusionary or not. The European notion of transferable, exclusive land ownership was not, as far as can be established, employed by Native Americans in this area in the early seventeenth century, but exclusive forms of usufruct, for instance, hunting, were in use. What the actual stipulations of the deal were is unknown. The only reference is a secondhand statement by a delegate to the Dutch States General, who, having no personal experience, presumed it to be a purchase and mentions that the colonists had “t’ eijlant Manhattes van de wilde gekocht voor de waerde van 60 gul.” It is actually unlikely that there was a “monetary transaction” at all, as is sometimes incorrectly stated. Most likely trade goods to the value of sixty guilders changed hands in order to establish a mutual understanding, including temporary permission to erect a small settlement. There is much more to be said about this transaction as well as other such deals, but I refer the commentator to the existing historiography on the issue.

Interesting story.

Unfortunate, however, that it perpetuates the fallacy that Manhattan was ‘bought’ from the Lenape, as the concept of ‘land ownership’ was unknown to the indigenous peoples.

The monetary transaction for land was only in the minds of the Europeans.

Any historical scholar should do thorough, unbiased research…….

Good point, but Dr. Jaap Jacobs did not say anything at all, during his interview with The Village Sun, about whether Manhattan Island was or was not purchased by the Dutch from the Lenape, or how the parties may have viewed whatever went down at that time, and the article does not claim or insinuate that he did. Yes, that question of whether Manhattan was, in fact, really “sold” and how the parties viewed whatever happened is not a new one. The article has been updated to say that the Dutch “claimed” to have purchased Manhattan from the Lenape.

That the Dutch “claimed” to have purchased Manhattan is unbiased and accurate.

My intent was not to demean the other research presented in the article, which, as I stated, was interesting, but only to correct an annoyingly ongoing untruth — that of the “purchase” of Manhattan from the Lenape by the Dutch.

As Manhattan at that time was an oasis of hunting and fishing, this may very well have been a fee imposed for the privilege to do so…sort of like a hunting license today. And then misconstrued by the Dutch (willfully??) to be a contract of ownership.

Not that it really mattered. The handwriting was on the wall, whether from incoming immigrants or the diseases they brought with them. The Lenape were not going to be the future light users of the land. Population pressure from Europeans who equated guns and buildings and contracts with progress would eventually be too intense to allow the Lenape to continue their lifestyle. It was only a matter of time.