BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Was Peter Stuyvesant, the notorious director general of New Netherland in the mid-1600s, really the colony’s largest slave owner — or is that just a myth? And lying beside him entombed under St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery is there an elderly former female slave who, after winning her freedom, became his housekeeper? And should there, in turn, now be a bronze bust of that woman, Mayken van Angola, added beside the one of Stuyvesant in the East Village house of worship’s churchyard?

Dr. Jaap Jacobs, a professor at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and a specialist in the history of the Dutch Republic and its colonies, is delving into these questions and more for a new book he is working on about Petrus Stuyvesant a.k.a. Peter Stuyvesant.

Jacobs has been sharing his research with St. Mark’s Church, which has embarked on an ongoing discussion on what to do, if anything, with its bust of Stuyvesant in its eastern churchyard — which was presented to New York by the Dutch in 1915 — and how best to memorialize slavery. St. Mark’s Church’s early congregants were slave owners, as were many prominent New Yorkers of that era.

Reverend Anne Sawyer, the East Village house of worship’s rector, met Jacobs two years ago when she was invited to a lecture he gave at The New Amsterdam History Center and The Holland Society of New York. Later on, she invited Jaap to help the church learn more about Stuyvesant and his involvement with slavery.

Gives Zoom talk to St. Mark’s

In his first Zoom talk to St. Mark’s members, this past January, entitled “Slavery in Stuyvesant’s World,” Jacobs laid out some of his findings up to that point. (For a video of that talk, plus a Q&A about it with Jacobs, click here.)

The basic facts about Stuyvesant are well known. As acting governor of Curacao, he lost his right leg below the knee to a cannonball while trying to recapture the island of Saint Martin from the Spanish, hence his nickname, “Peg Leg Pete.” After recuperating, he became New Netherland’s director general from 1647 until 1664, when the colony was ceded to the English. A fierce adherent of the Dutch Reform Church, he opposed religious pluralism in New Netherland, including other Protestant religions, such as Lutheranism, and was anti-Semitic.

“What I am presenting is a work in progress,” Jacobs said, in prefacing his presentation.

As Jacobs told it, the Dutch trans-Atlantic slave trade accounted for about 5 percent, or 554,000 people, of the 12 million Africans brought to the New World between 1606 and 1826.

In 1664, New Amsterdam’s population was about 10 percent to 17 percent black. Those who were enslaved were mostly “in the service of the Dutch West India Company,” while around 12 percent of New Netherlanders were actual slave owners, Jacobs noted. (New Amsterdam was located on Manhattan’s southern tip, while the larger colony, New Netherland, included not only New Amsterdam but Brooklyn, Albany and other settlements.)

‘This was not chattel slavery’

As Jacobs described it, many of the slaves were more like servants, as opposed to the kind of slavery seen in the American South. African slaves, for some of the colonists, were seen as “exotic” and “status symbols,” he said. In addition, both slaves and freed blacks were granted land along the “Common Wagon Road,” today known as Broadway.

“This was not chattel slavery, plantation slavery as it began to develop in Virginia and Maryland” once tobacco was hit upon as a cash crop, he said. “Still, African Americans in New Netherland had a very low status, whether they were slaves or not.”

For the Dutch, their Calvinist religion actually was used to justify owning slaves, in that “prosperity was [seen as] a sign of God’s favor.” At the same time, the Dutch believed slaves “had to be treated fairly,” and so it was accepted that they could run away from a cruel master. Slaves had to be taught Calvinism. They could not be sold to Catholic countries.

How many slaves did Stuyvesant own?

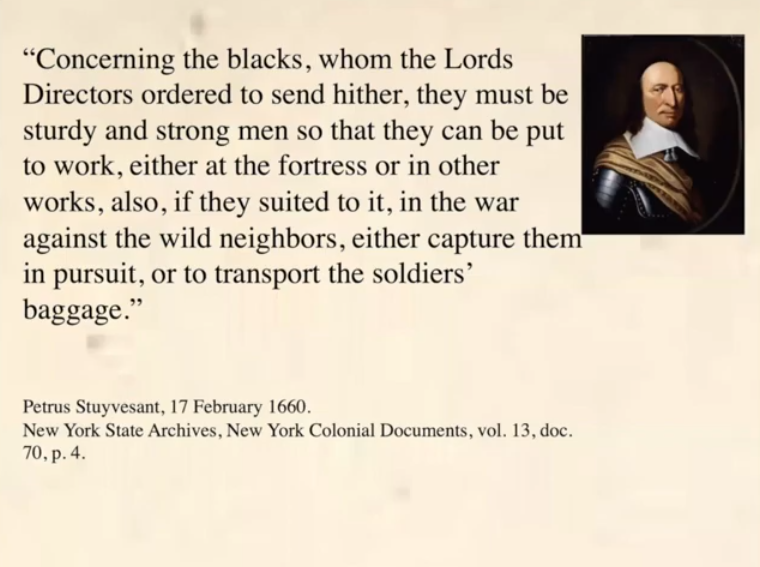

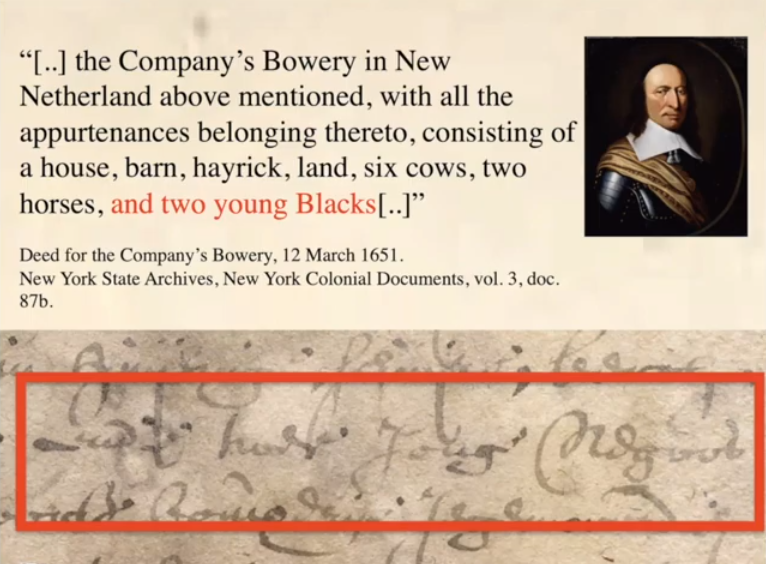

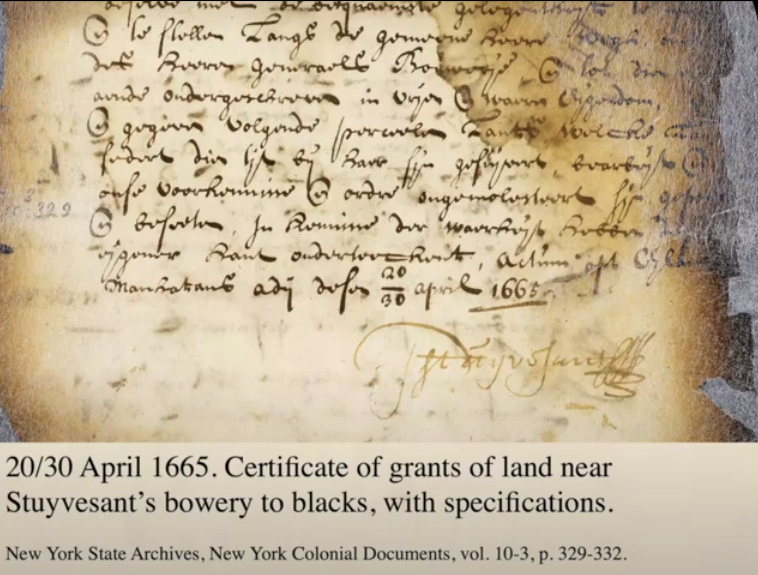

As for Stuyvesant himself, Jacobs said he had so far found only one piece of original source material clearly documenting if he owned slaves: the purchase deed for his farm, the Bouwerie, which the director general bought from the Dutch West India Company in 1651. The sale included “a house, barn, hayrick, land, six cows, two horses, and two young Blacks… .”

The widely held belief that Stuyvesant owned numerous slaves, Jacobs said, initially comes from a 1901 reference by historian Edward T. Corwin in his six-volume “Eccleseastical Records of New York.”

“Peter Stuyvesant, soon after he became Director-General of New Netherland in 1647, began to acquire lands on Manhattan Island in the vicinity of Third Avenue and Tenth Street,” Corwin wrote. “A little settlement soon sprung up at this place, known as ‘Stuyvesant’s Bouwerie’ or farm. For the accommodation of these people, as well as his own family and negro slaves, of which there were about forty, the Governor built a little chapel, and here, about 1660, Domine Selyns, minister at Breuckelen [Brooklyn], began to officiate on Sunday evenings.”

But Jacobs has been unable to find this claim backed up anywhere in early documents.

“There are no direct sources,” he said.

Also, parsing Corwin’s language, the scholar said, as he reads it, it’s not totally clear that Stuyvesant owned the “about 40” slaves mentioned. And, as was often the case under Dutch rule back then, probably some of those individuals were free or what was known as “half-free,” Jacobs added.

As for the fate of the “little chapel,” in 1793, Stuyvesant’s family sold it to the Episcopal Church for $1. Within a few years St. Mark’s Church was built on the site.

The story of Mayken

In the climax of his presentation, Jacobs related the story of Mayken van Angola.

“Mayken is an extraordinary woman,” he said.

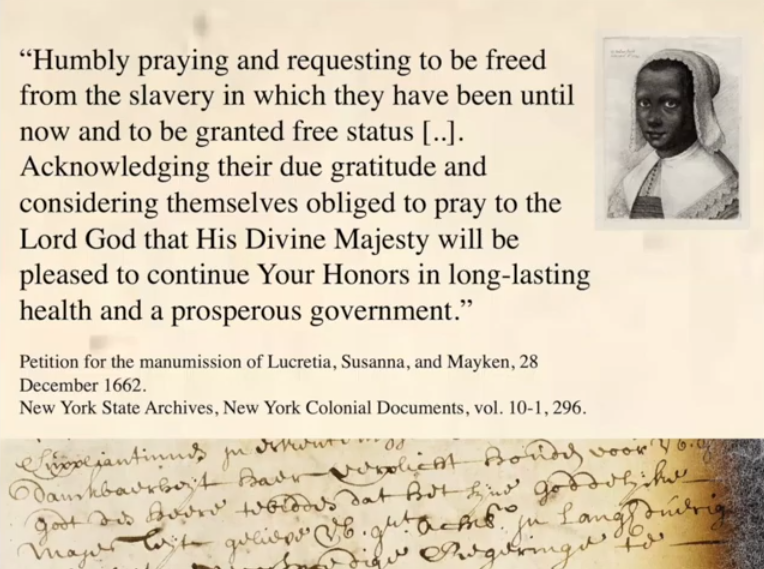

From Angola, as her name indicates, she was likely captured by a Dutch ship from a Portuguese ship and arrived in New Netherland in 1628. She lived in the Bouwerie, near Stuyvesant’s chapel. More than 30 years later, in 1662, she and two other women who also arrived with her in 1628 appealed to the Dutch West India Company to be manumitted — as in, freed from slavery — on condition the three of them would take turns coming to Stuyvesant’s house weekly to do housework.

Mayken was manumitted in 1664, along with her husband, Domingo van Angola. There was no mention at the time made of the other two women, possibly because they may no longer have been alive. That the appeals were made directly to the Dutch West India Company shows the women were not owned by Stuyvesant, according to Jacobs.

“Mayken is not a slave of Stuyvesant personally,” he said, adding, “Ownership [of slaves in New Netherland] is often very difficult to establish.”

As the English were about to assume control of the colony, there was a spike in manumissions, which Jacobs said was partly done out of concern for the slaves’ welfare under the new overlords. Former slaves were also given parcels of land, which was to keep the English from confiscating these areas, he added.

Honoring Mayken

Summing up his talk, Jacobs said, “Stuyvesant, for all his faults, can be considered one of the men who shaped New York. Yet Mayken, surely, must be one of the black founding mothers of the city.”

The professor noted that Mayken outlived Stuyvesant and his wife, Judith, who are buried under St. Mark’s Church. Then, in a colonial-era cliffhanger, he added one more thing.

“It is possible that Mayken and her husband are also buried there,” he said.

Jacobs then offered one possible solution for how to address the mixed legacy of the Stuyvesant bust.

“So does Mayken deserve a statue?” he asked.

No tales from the crypt

Finding out exactly who lies in the burial vault with Stuyvesant and his wife could be challenging, though. When Augustus Van Horne Stuyvesant Jr., who was described as a bachelor and a recluse, died in the mid-1950s, Peter Stuyvesant’s direct family line came to an end.

“Under the will [of Augustus], the vault was sealed,” Reverend Sawyer explained. “No one left could open the vault. No one has the authority.”

After Jacobs’s Jan. 31 talk there was a Q&A session with St. Mark’s members, fellow scholars and others who were on the Zoom. Ian Knife, a local artist originally from Zimbabwe who lives in Stuyvesant Town, has taken an interest in how the church is dealing with the legacies of Stuyvesant and slavery. He felt Jacobs’s take on Stuyvesant was too forgiving.

‘Don’t sugarcoat slavery!’

“I’ve lived through apartheid,” Knife said. “I lived through the ‘great men,’ Cecil Rhodes. … We’re never going to get ahead if we turn Peter Stuyvesant into a saint, into a hero, a great man. Let’s not sugarcoat slavery, please! I’m asking you!”

But, Jacobs replied, “I am not interested in elevating Stuyvesant to any hero status. … I would not care if his bust is removed from St. Mark’s. … I’m a historian. I work from documents, and what I find, I report. … My suggestion at the end of my story — to do something with Mayken — is nothing more than that. If there was a fundraiser now for another Stuyvesant statue or one for Mayken, I know where I would put my money.”

Another man on the Zoom call, St. Mark’s congregant Ernest Hood, said he didn’t care about the details of how many slaves Stuyvesant personally owned.

“It doesn’t matter if he had two slaves or 400 slaves,” he declared. “He still owned slaves. It doesn’t matter if he had one or 500.”

‘Telling the truth of history’

Before Jacobs’s talk, Reverend Sawyer stated, in part, “Members of this parish owned enslaved people. And we are committed to telling the story and learning from history. … We hope to have the parish engage in dialogue and to discern how best to use and to care for the items that have been entrusted to us and how best to tell the truth of history to all who come to visit this place.”

One of those “items” she was referring to, no doubt, is the Peter Stuyvesant bust outside the church, which gazes toward the vault where the colonial director general lies. The church is considering creating a slavery memorial but its form has not been determined yet.

More from Jacobs on city’s early slavery

Meanwhile, Jacobs is giving another Zoom talk to St. Mark’s Church members on Sun, Aug. 29, at 1 p.m., entitled, “New Light on The First Decades of Slavery in New Amsterdam.”

Per St. Mark’s Web site, “In this talk, Jaap Jacobs will shed new light on the introduction of the institution of slavery in New Amsterdam and its early development. Starting with the first arrival of black people on Manhattan, Jacobs’s talk will focus on the context of their voyage, their gradually changing status from bonded laborers to enslaved, and the background of slavery in the early Dutch Atlantic [colonies].”

The talk is free and open to the public to watch.

In an e-mail, Jacobs confirmed to The Village Sun that, in his Aug. 29 presentation, he would put forward “a firm date for the involuntary arrival of the first blacks in New Amsterdam.” He said, if time permits, he might also touch on the unveiling of the Stuyvesant bust at St. Mark’s Church in the early 20th century. But he said there “would not be much news” to report on any unidentified occupants of Stuyvesant’s burial vault.

Fascinating.

“He opposed religious pluralism in New Netherland, including other Calvinist religions, such as Lutheranism.”

Lutheranism is not a Calvinist religion. Calvin was called a Lutheran in his early life but eventually created his own, different theological beliefs.