BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | At their annual fundraisers, the Downtown Independent Democrats usually honor a prominent politician, along with an activist or maybe two in labor or community issues.

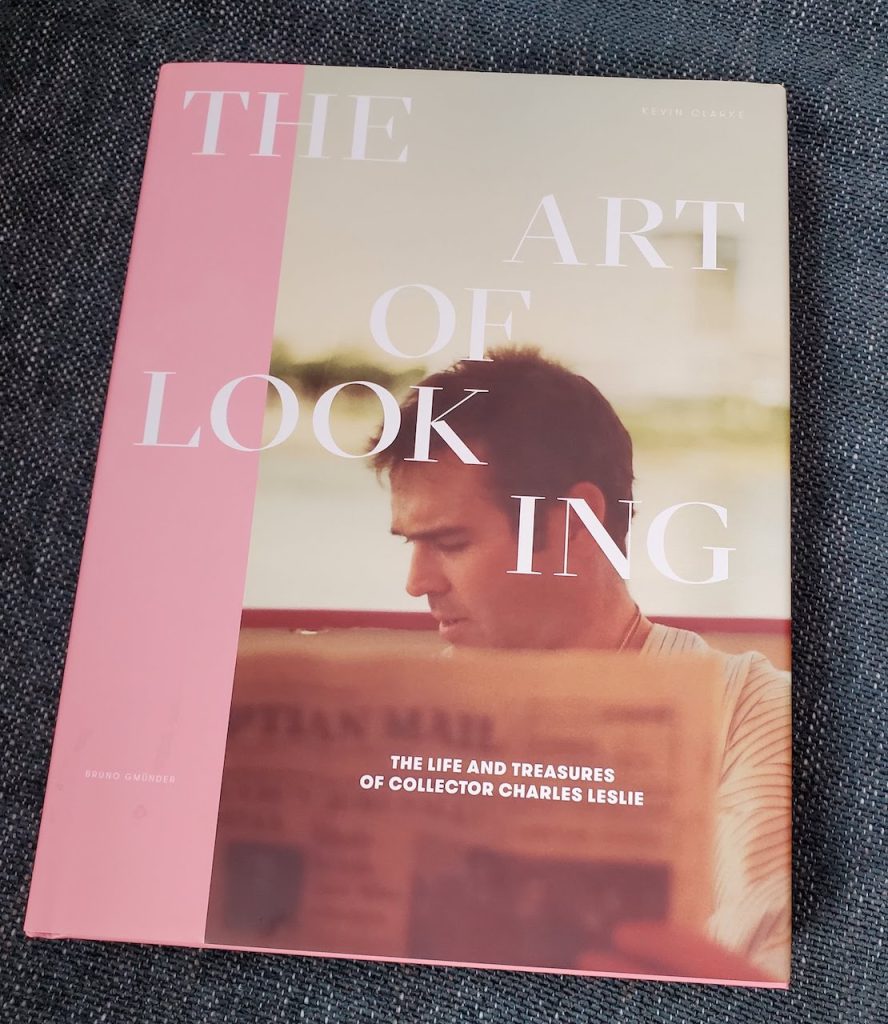

Last December, the club — which was marking its 50th anniversary — also honored one of its own early members, Charles W. Leslie, with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

Leslie, 90, was a prominent activist in Soho in the 1960s and ’70s. In 1977, with the backing of D.I.D., a Reform Democratic club, he campaigned for district leader, becoming one of the first openly gay candidates to run for office in the U.S., following Harvey Milk and Jim Owles.

His ground-breaking election bid, though, was met by virulent homophobia from so-called Regular Democrats in the eastern part of the district, Little Italy.

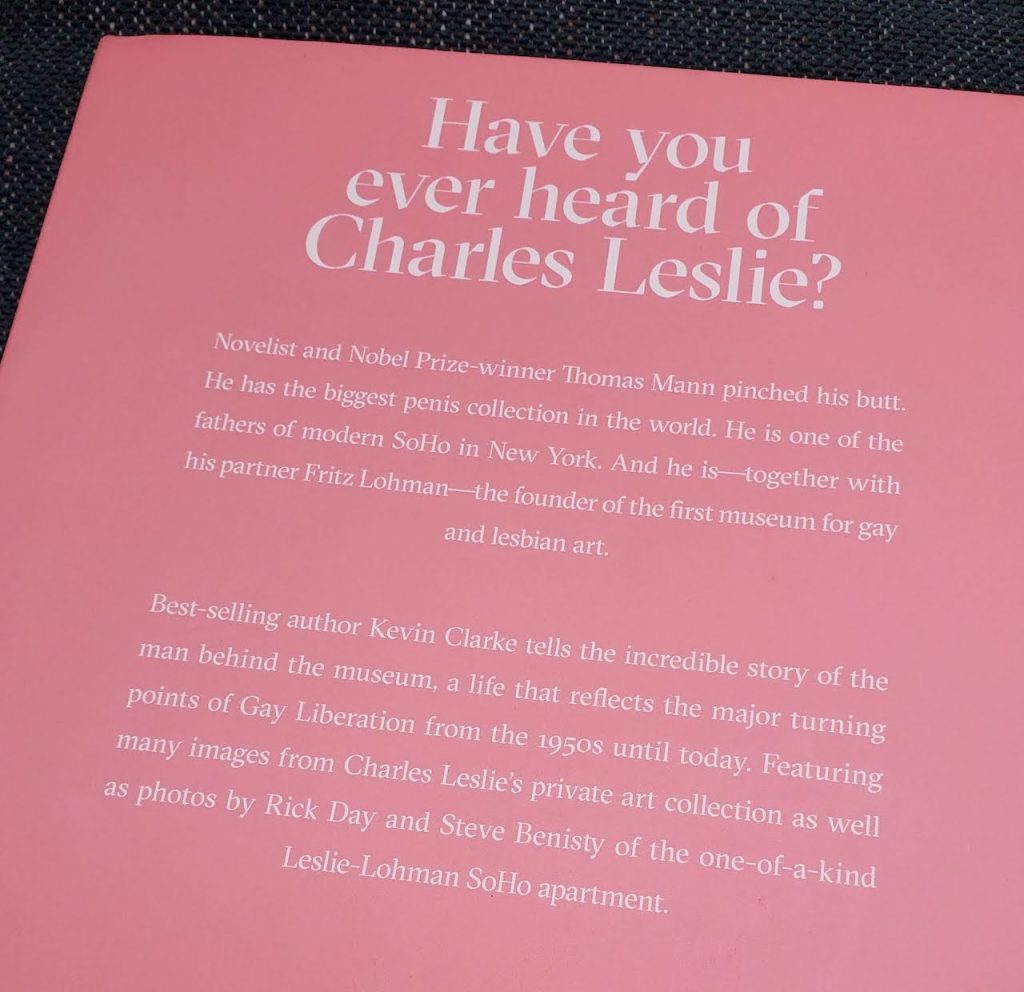

Leslie later went on to co-found the world’s first museum of gay and lesbian art, also in Soho.

“Charles is Soho’s Zelig,” remarked Sean Sweeney, a longtime member and former president of D.I.D., referring to the ubiquitous Woody Allen character. “He’s been present and active in every major occurrence and development in the area: being an early loft pioneer (1968); participating in the Stonewall Riots (1969); creating the Leslie-Lohman Foundation for Gay and Lesbian Art (1969); fighting for the legalization of artists’ living in Soho (1971); helping defeat Robert Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway (1969-72); pushing to landmark Soho (1973); being politically active and running for district leader as the nation’s third openly gay candidate (1977); restricting Soho as a nightlife hotspot (1977); preserving queer art during the AIDS crisis (1980s); and co-founding the Leslie-Lohman Museum, the first accredited museum for gay and lesbian art in the world (2014).”

Leslie grew up in Deadwood, South Dakota, and moved out the day after graduating high school. He lived in Los Angeles for a while, then in Venice and Amsterdam, and studied French at La Sorbonne.

He moved to New York City in the early ’60s and to Soho in 1968, when it was still an industrial area, buying a loft in the same building as jazz great Ornette Coleman. He and his partner, Fritz Lohman, both with a fondness for queer art, founded the Leslie-Lohman Foundation for Gay and Lesbian Art in 1969, the same year as Stonewall.

Shortly thereafter, they opened the Leslie-Lohman Museum in their Prince Street loft. They expected perhaps 100 people to show up for the opening but hundreds poured in that weekend. Following the massive event, they operated the museum in a downstairs gallery on Prince Street.

Leslie and Lohman slowly amassed gay art, but the AIDS crisis set their collection off with a new urgency. Many gay artists died of the disease and their families wanted no part of their artistic legacy. Works that would have been tossed into the garbage were collected by Leslie and Lohman.

They closed the gallery, however, during the AIDS crisis. In 2006, they opened the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art at 26 Wooster St., where it still resides today. Lohman died in 2009.

All the while, Leslie was in the forefront of the community’s struggles. He worked to stop Robert Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have destroyed not only Soho, but also Chinatown, Little Italy and the Lower East Side. The highway would have been bulldozed through Downtown Manhattan to connect the East River bridges with the Holland Tunnel.

Leslie also joined the Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture and worked with its founder, Margot Gayle, to get Soho landmarked in 1973. He was a founder of the Soho Artists Association, the precursor of the Soho Alliance, which in 1971 successfully pushed for legalization of artists living in Soho’s manufacturing-zoned buildings.

Presciently, he and his partner bought several Soho storefronts in the 1970s, when no one thought the area would become a retail hub. The properties’ income has enabled his philanthropic work.

Leslie has traveled extensively throughout the world and currently has a home in Marrakesh, Morocco, where he spends spring and autumn.

Kathryn Freed, who later went on to become a city councilmember and judge, was Leslie’s running mate for district leader. After moving into Soho in 1969, she had been elected district leader twice. The male district leader, though, had moved away, and Leslie decided to try for the seat.

“When we ran, we were gay-bashed terribly by the Regular Democrats,” Freed recalled. “We lost. Frank Russo’s old club ran against us.”

For the next election, however, the districts were reapportioned and she was reelected. Leslie chose not to run again.

“He was always an activist,” Freed noted. “And he was one of the original organizers of the Soho Artists Association; that’s how we started organizing to save the Soho Cast-Iron Historic District.”

In a 2019 video interview, Leslie said of his personal collection of gay art in his loft, chuckling a bit mischievously, “Some of my stuff is rather on the naughty side.” He unabashedly claims to have “the world’s largest penis collection.”

“We have preserved a lot of stuff that ordinarily would have been destroyed. We were constantly at bedsides and memorials and funerals,” he recalled of the AIDS crisis. “But it did spur us on to save their work — that’s what was left. It became a crusade with us.”

Be First to Comment