BY DASHIELL ALLEN | Walking down Park Avenue in Midtown on a brisk fall morning I heard a shrill, faint, chirping sound coming from the sidewalk.

Looking down I saw a flailing migratory songbird, clearly injured, hopelessly attempting to fly away from the spot where it had fallen after striking a nearby skyscraper. Lots of office workers walked by, expressing momentary concern, but clearly with too much on their mind to worry about the wounded chick in front of them.

Deciding to take matters into my own hands — I called up Michelle Ashkin, a wildlife expert and Battery Park City resident, who directed me to the Wild Bird Fund on the Upper West Side, of which she is the co-director of education.

The bird, I later found out, was a juvenile swainson’s thrush that had suffered a concussion. It “bounced back quickly” after receiving pain medication and continued on its migration to as far south as Peru.

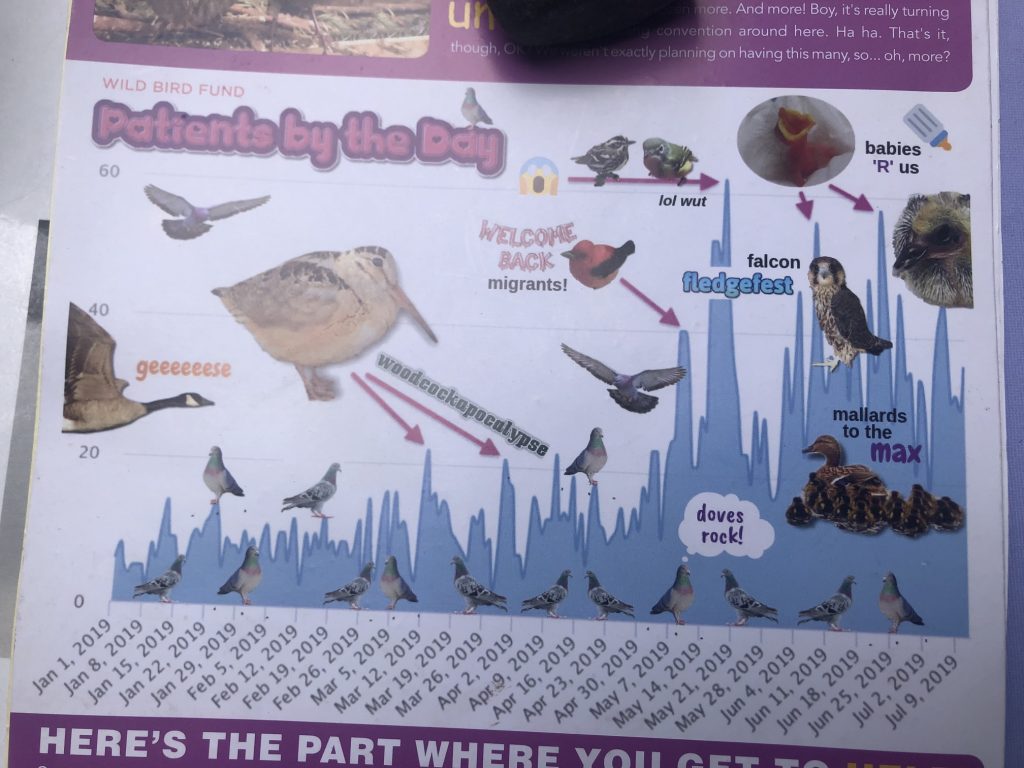

The Wild Bird Fund, New York City’s only wildlife rehab center, has received more than 8,000 patients this year, according to spokesperson Catherine Quayle, who addressed a Community Board 1 meeting last month.

“Approximately 1,200 of those this year will be window-strike patients,” Quayle said. “We can give them anti-inflammatory medication. We can give them wound care. But still, after all that, only 40 percent of the ones we treat survive to be released.”

Building strikes are the most common cause of death for the millions of birds migrating through New York City each year, taking between 90,000 to 230,000 avian lives, according to Kaitlyn Parkins, the associate director of conservation and science at New York City Audubon.

Back in mid-September an Audubon volunteer’s photograph of 266 dead birds she found in the World Trade Center complex went viral, leading to massive media attention.

The ones most commonly found are white-throated sparrows, American woodcocks, common yellowthroats and northern parulas. Interestingly, the city’s native pigeons and sparrows have very few glass collisions.

“There’s a hypothesis that some of these other species are slower flying and they’re less likely to be scared of people,” said Parkins, meaning that even if they were to collide with a building they’re less likely to get injured.

Within the city, the majority of collisions have been reported in and around the Financial District in Lower Manhattan.

Most birds migrate at night. Light pollution from the city’s towers “both attracts and disorients migratory birds,” sometimes calling them to fatally crash, Parkins said.

That leads birds to “get trapped and kind of exhausted and land in places that they shouldn’t,” such as on a tree at the foot of an office building on Park Avenue.

Migratory birds cannot distinguish between a panel of glass and the open sky, so often, after seeing the reflection of a tree — or really anything — in a building’s glass panel or window, they fly toward it, often with fatal consequences.

“This is of course fixable,” Parkins said. “We can put visual indicators that are fairly close together. Those visual indicators are solid barriers that birds can see and say, ‘O.K., I can’t fly through that and it’s so close to the other one that I can’t fly between them,’” she explained.

New York City’s Local Law 15 — which recently went into effect — requires that all new construction implement bird-friendly design up to 75 feet high.

Seventy-five feet was a “compromise” that wouldn’t be “fought to the death by REBNY [Real Estate Board of New York] and other developers,” according to Parkins, given that “the vast majority of collisions are on the lower levels of the building.”

But the law doesn’t require buildings to be retrofitted to prevent bird collisions with glass panels, and only applies to developments with a ULURP (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure) that began after the measure went into effect.

On a recent early Friday morning before sunrise, I met Nick Kaledin, a retired Broadway union organizer, at the base of One World Trade Center.

Kaledin is a volunteer for New York Audubon’s Project Safe Flight, which every spring and fall monitors around 20 buildings deemed at “high risk” for bird collisions.

We spent an hour walking around the W.T.C. campus and came across one bird, identified as a warbler, that appeared to have been long dead.

It’s already late in the bird migration season — which lasts from September through mid-November. On Sept. 15 Kaledin saw 18 downed birds, 75 percent of them dead.

This year Project Safe Flight has had more volunteers than ever before — and witnessed a record number of known collisions.

“There’s just been an interest in birds and birding in the pandemic,” Parkins said, “and I think for a lot of folks it’s hard to suddenly notice birds without suddenly noticing bird-window collisions.”

She doesn’t think that means there’s actually more collisions taking place, noting, “I attribute it to the fact that we’re monitoring particularly bad buildings and that we have far more volunteers.”

Even so, “the project wasn’t designed to look at long-term trends,” she said, but rather to make a convincing case to building owners that mitigation measures, like turning their lights off and bird-proofing their glass, need to be taken.

“A lot of them think that putting a window film will ruin the aesthetics of the building, which is unfortunate,” she said.

“There are a lot of building managers and property owners out there that absolutely would not change their building unless they’re forced to, and bad PR is a great way to get them onboard,” she added.

At the same time, the passage of Local Law 15 has seen an increase in the diversity of glass options available. Notably, New York University’s towering new building at Houston and Mercer Streets is bird-friendly, as is the Javits Center.

While collisions with glass in New York City present a threat to migratory birds, Parkins emphasized this is equally as much a suburban and rural issue as it is urban.

“Even if it’s just one or two a day at a couple windows,” she said, “that adds up to huge numbers.”

“New York is about to raze a LES park”

https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-letter-nov-11-20211111-bm6sqwzjm5anlny6pv72x4cjve-story.html

Save East River Park for migratory birds!