BY LINDA JUSTICE | The East Village has endured waves and cycles. But will it survive this time? Most say not!

I offer this article because I want us as a neighborhood and city to become truly aware of what we are losing, to bring it to full consciousness so we can make the best decisions and to make sure we will be satisfied with the outcome.

One peculiarity of New York is how each block has its own unique vibe.

In “St. Marks Is Dead,” Ada Calhoun wrote: “This street is for the wanderer, the undecided, the lonely, and the promiscuous.”

Yes, in general the whole East Village can be considered the home of riffraff, legendary artists, radicals and dissidents. But I would like to share another story, another beginning often missed. I would like to take it up a notch.

At 27, I found myself moving to St. Mark’s to attend the School of Visual Arts. I knew nothing about New York. And I can only speak from my own viewpoint, that on St. Mark’s Place between Second and Third Avenues, regardless of the riffraff, were people who had strength and determination to suffer under the weight of staggering rents, crime and corruption, to follow their dreams, and care for their families, or study.

Many young people living between Second and Third attended New York University, The Cooper Union or S.V.A., while others created businesses. My close friend Sandra followed in her mother’s footsteps by opening a homey Italian restaurant featuring her own Northern Italian recipes. She worked her fingers to the bone to pay rent. Her place became a center for friendly gatherings on an otherwise crazy, dystopian block. Previously, she had helped design and cooked the menu for Khyber Pass restaurant. Those folks crossed the Khyber Pass, ending up on St. Mark’s, where they created their superb Middle Eastern cuisine.

And St. Mark’s Bookshop. One partner in the bookshop told me, as I sat next to him at the counter inside B&H Dairy, that it was his only meal for the day, homemade soup with challah bread, that kept him alive so he could help build that store. Another person wrote that when St. Mark’s Bookshop closed, for her, St. Mark’s Place ended. It was that vital to the community — a wellspring of contemporary thinking.

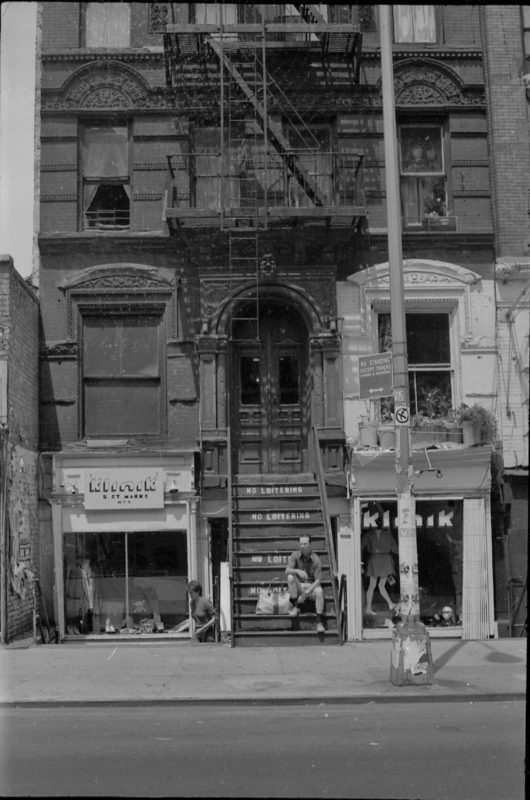

(Photo by Carole Teller, Courtesy Village Preservation)

Heads and Tails, Hair and numerous other hair salons, packed on weekends, offered haircuts as good as any Uptown salon but at affordable prices.

These venues were well thought-out, offering warmth and cohesion, as did many other shops too numerous to mention here. They were contributors to the legendary music and dance scene.

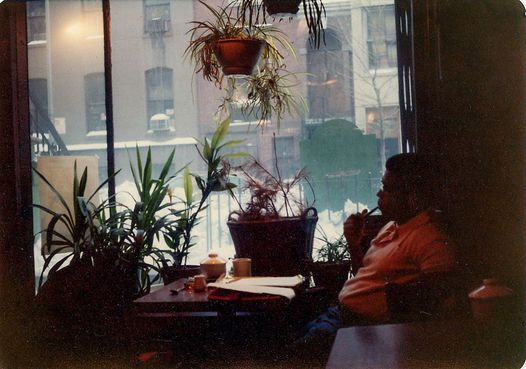

The summer I moved in, most of the stores were boarded up. At La Fregata cafe (Ada Calhoun lived next door), the house specialty was cafe au lait served in oversized ceramic U.S. Navy bowls, “with lids.” The cafe became a gathering spot for Peruvian artists, American artists, students, poets and theater groups.

And at 9 p.m. or so, if La Fregata was full, the owner, Ed, would shut the doors and offer free coffee on the house and we’d all hang out until the wee hours of the morning. Of course, in those days, you could smoke cigarettes inside.

So what I wish to say is that St. Mark’s is not dead. It is being systematically killed off.

What determines a neighborhood? What confluence of ideas? What group soul arrives at the same time to usher in something new — and who decides?

Kurt Vonnegut, in “Cat’s Cradle,” called it a “karass.”

A karass is the Bokononist term for a group of people brought together to do God’s work — though the purpose of that work is not something of which they can ever be fully aware.

I was so lucky to be a fly on the wall of many creative ventures. Gosh, when I arrived, the Tibetans were here, the Hare Krishnas, the Orthodox Christians, shamans. Weiser’s Bookstore — the oldest occult bookstore in the nation — was full every weekend with young people sprawled all over the floor reading mystical texts. One gulp and I was in.

The Human Potential Movement was here: Werner Erhard’s EST, Robert Fritz’s DMA, Gavin Barnes’s Direct Centering, Arica by Ichaszo. The Open Center held its first meeting at Cooper Union. The Sufis were here, the whirling dervishes — offering a great influx of spiritual energy into the city.

People were reading Carlos Castaneda and “Rolling Thunder.” They were attending Sun Bear’s Rainbow gatherings. The city was alive. Amid all this chaos, people were trying to wake up.

It seems my every wish was granted. I studied Byzantine iconography in the basement of an Orthodox church, led by Russian masters who needed translation. In our little cubbyhole, we mixed paints in the ancient alchemical tradition. Although not Orthodox, I attended an opening ceremony led by a beloved French bishop across from my apartment, and got to attend a small gathering with him afterward. He walked in, poured himself a whiskey and raised it to the heavens: “Does anyone here really believe in God!” he exclaimed. My kind of priest: One who is always questioning. And I was able to see films at Theatre 80.

I was here alone, without family — and passing Theatre 80 every day gave some kind of assurance of cultural stability. There were folks we had all grown up with, enshrined in photographs and memorabilia — and handprints in cement out front. The theater was created by Howard Otway — with his young son Lorcan helping him dig out the venue’s floor by hand to deepen it.

When I wanted to work in the theater, I was able to volunteer in the East Village with Mabou Mines at the Public Theater and with Jun Maeda at La MaMa. I was horrible at everything, finding it hard and difficult. But I jumped in anyway just to be around great minds and creative thinking.

This was all available. So, I say to anyone who feels that most came here to take drugs: There were others who came here as seekers, coming from the doldrums of suburban life, where the arts were something one would only see in a Sunday magazine.

Here, I would like to take a step back to 1859 and the opening of The Cooper Union and dedicate this article to Peter Cooper and his visionary quote: “I look to see the day when the teachers of Christianity…will be reconciled to the government of love, the only government that can ever bring the kingdom of heaven into the hearts of mankind either here or hereafter.”

Peter Cooper believed that education should be free. He believed in progressive thinking. He believed in inclusivity. He believed in radical ideas. He built the Great Hall, inviting Abraham Lincoln to lecture. I saw Kurt Vonnegut lecture there in 1984.

But students still needed places to live. I was trying to find out how the East Village came into being — how the particular notion of it being a cash-poor neighborhood came to be.

I want to say this loud and clear: The East Village did not “just happen.” It was created! Peter Cooper set in motion what the East Village would become. Everything here was created by people who lived here, moved here, made it their home. The commercial places that opened did so because they saw “need” not “greed.”

Some, like Ed of La Fregata, were visionaries. He went on to create the Cloister Cafe on E. Ninth Street. With the help of his wife, Eva, and a few friends, they restored the premises by hand back to the era of Peter Stuyvesant. I remember helping him arduously dig away the asphalt to expose the original cobblestones. (His fingers were bloody and raw.) And everyone was so excited to help him create his vision.

And then there’s Kiehl’s Pharmacy. It began as an apothecary in 1851. More than 100 years later, in 1961, Aaron Morse took it over. Morse had let his fluffy, jet-black hair grow out and had perfect white skin. One day I walked in and, just like the queen in “Snow White,” he was looking into a cosmetics mirror, examining his red lipstick. They made their own and he told me he tested each color himself. There were no ornamental displays in the store. Amid its worn wooden floors, shelves and rustic cabinetry were displayed merchandise, plus “a museum’s worth of Harley Davidsons,” his private collection. And the adjoining room was turned into a hangar with stunt planes — his own! He was a former fighter pilot. This was the kind of person who made up the East Village, with ingenuity, creativity, passion.

The East Village forced its way into being a community where anyone could come, get a part-time job washing dishes, and rent a room to pursue his or her interests.

The East Village, for all of its problems, has always been a unique, thriving, creative community of diverse streets, cultures and religions, and eateries offering homemade food, all coexisting and being totally creative — this is what was killed.

People refer to buildings — like Theatre 80 St. Mark’s — being bought and sold. But they are not just “buildings.” They are what make the community thrive, give it uniqueness, give people who reside here pride and a sense of purpose and belonging.

We confronted cycles of city corruption, violence, theft. There were murders. Crime turned into blood sport, like the wilding gangs who passed through one afternoon, chasing a small, young teenager out into the middle of traffic at Astor Place. Nobody could stop them. A new cycle had begun, a vicious cycle of violence. The cycle of lightheartedness ended, took a nosedive.

In 1989, a brutal killing followed on the heels of the Binibon restaurant murder, which had seen writer Norman Mailer’s protégé Jack Abbott slay a waiter. At Sandra’s restaurant, her upstairs neighbor, Milan, whom I had had dinner with the previous week, took in a homeless man. They got into a fight over politics and the man shot and dismembered Milan. The victim, an immigrant and a veteran, was never given a soldier’s burial, but was interred in Potter’s Field.

Yet, somehow we thrived. We survived 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy. But what is happening now is not only destroying buildings, but any unique neighborhood spirit that had been created and fostered.

“After a night of inebriation in the E.V., I stopped at a pizza place…”

My friend, a shop owner, informed me that New York will be driven by real estate. He shrugged, sitting at the counter smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee. I also shrugged. So now we will foster in folks who stand around with hands in their pockets eating ice cream, as we walk through the broken glass of smashed beer bottles from the previous night, the shards cutting into our dogs’ feet, and we will wonder what happened, and we won’t know what to do about it.

It takes a very long time to create a neighborhood. This one began a new cycle around 1977 with the influx of young people from N.Y.U., Cooper Union and School of Visual Arts, mixing with the folks who came after WWII. Boarded-up shops were opened to allow in new creativity. For a while, businesses and art flourished side by side, but for only a very short while.

And who knows what brings in a new cycle. Is it a matter of what the human spirit can endure and how much it can take, before it becomes a world of restless disembodied zombies?

So we’ve earned our right to remain here, thriving and creating, saving what is left and reinvigorating where possible and imagining a future.

When I first moved here in 1977, in front of my building someone had thoughtfully planted a honeysuckle bush. Now, it’s gone! I wonder how many of our children know the scent of honeysuckle.

And who knew that one’s personal spiritual cycle could begin in such a city as New York, and in such a neighborhood as the East Village, where all traditions intersect — one’s inner canvas bursting open and one’s deepest aspirations realized in this crazy, crazy neighborhood.

Justice is an artist and writer living in the East Village.

I forgot to mention that I felt that the neighborhood at the time was a particularly diverse one, with a mix of artists, writers, theater people, dancers, college students, dropouts, working-class people, immigrant groups from Ukraine, Poland, Puerto Rico, India, people of so many ethnicities and languages, that was so stimulating and made it an especially creative place to live and work. I understand that parts of Queens now are somewhat like that, but for how long? Who knows.

Thanks for you comments. Much appreciated . I wrote this article very cautiously, wondering if I was the only one who felt this sadness. But others have made nice comments about their sadness at seeing it go.

The East Village was my home for 45 years, from 1972 to 2017. I moved there to attend the Cooper Union as an art student, and I moved into a top-floor loft in what became the Village Voice building in 1975. It was a great place to live for many decades. It was a neighborhood that was affordable for artists, a community where an artist could make mistakes yet survive.

Imho, 9/11 and Giuliani/Bloomberg changed the vibe. In 2015, a men’s clothing store opened up around the corner on Lafayette in NoHo (by then NoHo was already the second-most expensive residential neighborhood in NYC, after TriBeCa, where the prices of men’s sports jackets started at $2,700 and went up from there. I knew then that it was a good run, a great run, and that it was time to go.

I am in Newburgh now. The vibe, in part, is that of the East Village of the 1970s, but the speculators are circling.

Thank you. Now I’m curious about Newburgh. Maybe I’ll go t there.

Thanks for mentioning this fine article, Linda. I remember seeing Quentin Crisp a couple times near Gem Spa. RIP both Quentin and Gem Spa.

@Bill: Quentin Crisp lived on East 3rd street, in a rooming house “on the block that’s the Hell’s Angels Eastern Seaboard Headquarters,” he was fond of saying. Both he and the Angels are gone, sadly enough.

I moved to the city in 1980 to attend the Cooper Union, and felt like an outsider in part because in those days people weren’t shy about asking “Whaddayado? Whaddayado? How much rent do you pay?” In 1983, my rent, at $750, was more than I could afford, so my parents paid it; I was a disabled student at the time, having survived a devastating car crash in 1981. If I were to admit my rent was $750, people also weren’t shy about sneering, “That’s *expensive*!”

I absolutely would love to return to the New York of the ’70s and Æ80s, but I wasn’t happy about coming home one night — for instance — to a junkie shooting up in his leg on my front steps. People prefer to gloss over memories like that.

Great article, Linda. Hope people take notice!

Love this. I came to the EV in June 1980 to homestead an abandoned tenement (in which I still live after we bought it from the city in 1988) and patronized many of the long-vanished places mentioned in the article. Despite the poverty, empty buildings, drugs and crime, back then the EV thrummed with a vibrancy and with strands of life that intermingled despite their differences — punks eating in the Polish and Ukrainian restaurants or the music and art scene colliding — but not in a bad way — with the blue-collar workers who still lived here, for whom places like Leshko’s and Brunetta’s opened at 5 a.m.. so they could get breakfast before they went to work (and a full Leshko’s breakfast special cost a whopping 75 cents). The neighborhood offered a sense of freedom, for want of a better word, and people could come to it thinking that anything was possible, since they could afford to live here without being subsidized by Dad, work on Wall Street or be an NYU student. It was an amazing time that will never return, sadly enough, and I truly believe that the entire city is the poorer for the fact that this crappy, dirty, at times dangerous, semi-abandoned neighborhood with collapsing buildings and empty lots filled with abandoned cars and shopping carts, but in which people like Richard Hell, Allen Ginsberg, Quentin Crisp, Madonna, Basquiat, Joey Ramone and so many others felt comfortable enough to live, has disappeared forever.

I love your comments!!! Similar comments can be made about so many of the city’s neighborhoods that are now unrecognizable in their current sterile, suburban state.

Thank you for your additions. I only had 2,000 words. I met and befriended Quentin Crisp and I feel a new book is in order. There are so many things to think about. And the new folks that bought a recent building told me: They will think about what to do. Well, we had what to do! And people can’t see it as they are all about money now. Thanks for your responses.