BY DAVID DAVISON | If you drive across West Houston St. today and stop in front of a renovated luxury apartment building at No. 124, you might not see anybody special.

Fifty years ago on a late fall day, my friend Paul pulled up in front of that building, driving an old step-van truck with the words “Ashes & Sand” painted on the side. Standing there waiting for him was Bob Dylan, in a wispy beard, wearing blue jeans, an old shearling jacket and a fur hat with ear flaps. He just blended in with Villagers passing by.

Paul had just driven down from Woodstock with his friend Walter, who was employed as Dylan’s caretaker. The step van was loaded with furniture and boxes. The plan for the day was to pick up the future Nobel laureate and help him move some stuff between his house around the corner on 94 McDougal St. and the studio he rented on the ground floor of the building on West Houston St.

“I had seen so many black-and-white photos of Dylan that my first thought was, ‘Oh my God, I’m meeting Bob Dylan and he’s in color!'” Paul recalled.

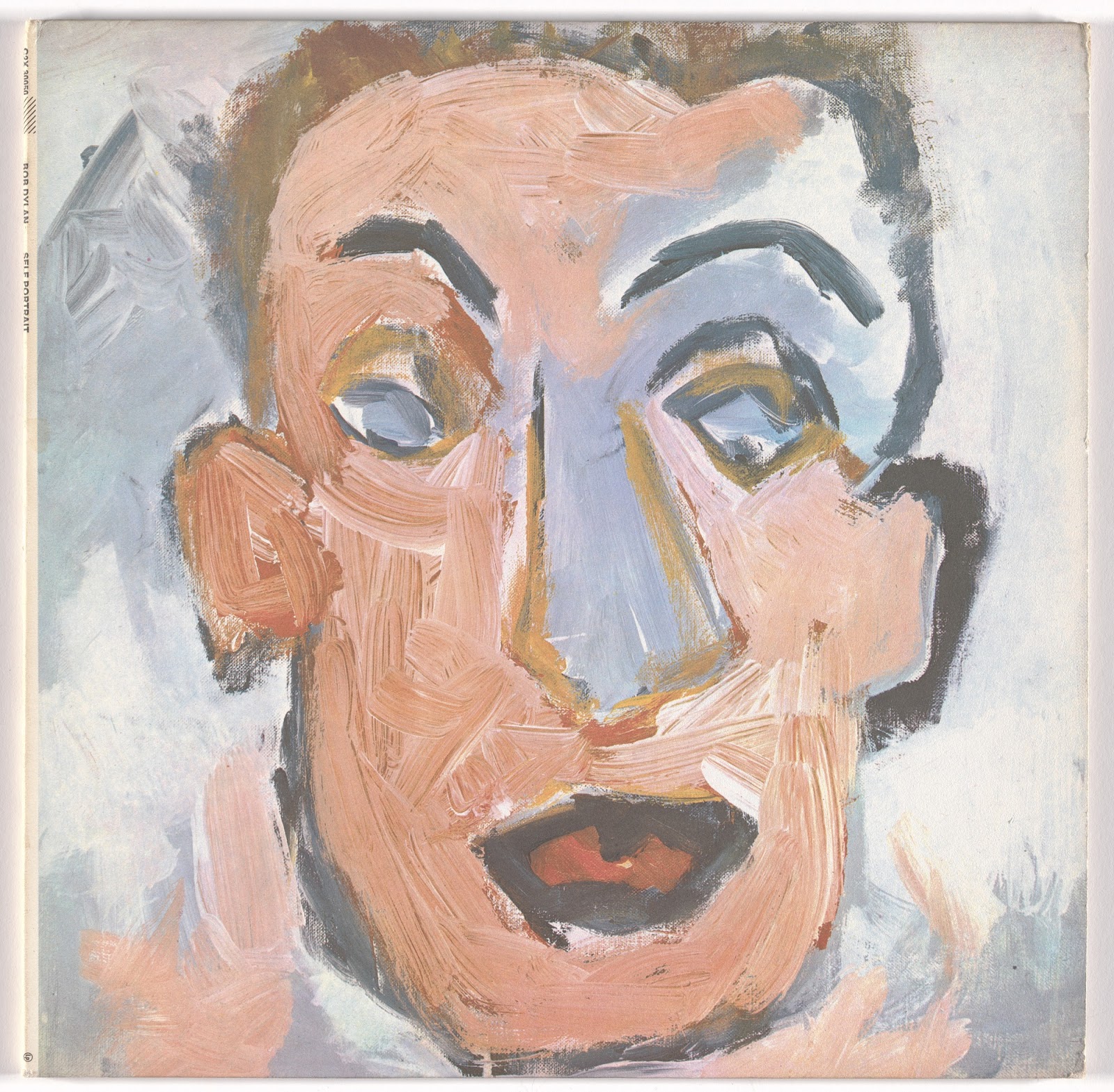

Paul was determined not to say anything awkward or foolish. The studio, Paul remembers, was full of various instruments, mixing boards, mics and a stand-up piano against one wall. Dylan worked on that piano developing material for his voice-changing country album, “Nashville Skyline,” as well as “New Morning” and “Self Portrait,” a double album released early that year in 1970 that was widely panned by critics and fans alike.

Dylan was not yet 30 years old. Paul, almost 21, grew up in Queens, and was then living in a small cabin in Woodstock. Paul and Walter became friends while studying with an art teacher who lived across the road from Dylan’s house in Woodstock. The old step van they drove that day had served as the equipment truck when Dylan toured in the mid-Sixties with a group that later changed its name to The Band. Ashes & Sand, Inc., was the name of Dylan’s touring company. Or, as Dylan once told Walter, “It’s the name of a demolition company.”

As the moving job got going, Paul and Bob were carrying a piece of furniture together up the steps to the second floor of the MacDougal St. home. At the top of the landing, hanging on the wall, was the original self-portrait in acrylic that Dylan used as cover art for the album.

“I was busting at the seams with a thousand questions,” Paul remembered. “I had heard he could be edgy and unfriendly, but he had a gentle air about him. All that day he seemed like a regular guy. A family man.”

Once the work was done, Paul and Walter headed north with the step van loaded with furniture destined for the Woodstock house. Somewhere on the West Side Highway the old truck broke down. They found a pay phone up on Riverside Drive.

“I don’t know what to do,” Bob said. “Just leave the truck and come back down to the house.”

Standing in his kitchen, Bob pulled out an address book and looked through it and said, “All my friends are musicians and they won’t know what to do either.”

Sara Dylan was watching their four little kids. One of the toddlers was hanging onto his dad’s pants, peeking out from behind Bob’s knee, looking up at Paul.

After an informal dinner, Paul volunteered to stay over in Queens with his parents to help deal with the step van the next day. Walter took the bus back to Woodstock. Later on, Paul sat on a couch next to Sara while Bob sat on the carpet playing with his kids while they all watched “The Johnny Cash Show” on ABC TV. At one point, Sara turned to Paul and said, “Isn’t this awful?” Paul didn’t know what to say.

Bob had appeared on the show a year before, performing “I Threw It All Away” from “Nashville Skyline.” Years later in his book “Chronicles: Volume One,” Dylan wrote, “Having children changed my life and segregated me from just about everybody and everything that was going on. Outside of my family, nothing held any real interest for me… .”

Bob had given Paul his phone number to check on the situation the next morning. Paul picked up the truck and drove back to MacDougal St. where Bob gave him a personal check for $45 to reimburse him for the towing costs. Then he drove the step van back to Woodstock. Over the next two years Paul would occasionally work with Walter doing some gardening chores around Dylan’s house.

A little over a year later, Paul had a show of his paintings. He went down to the Village, screwed up some courage and rang the bell at 94 MacDougal St. A housekeeper answered.

“Is Bob or Sara home?” Paul asked.

A moment later, Sara came to the door, hopping mad. Fans and weirdos of all kinds were a constant menace. Paul managed to reintroduce himself, and Sara realized who he was, and smiled. Paul took a deep breath and handed over a formal invitation for her and Bob to come and see the gallery show.

Did they ever stop by to see Paul’s paintings? He doesn’t know. But Paul’s full-color memory of seeing Bob Dylan’s self-portrait on the wall, with the legend himself standing right underneath it, carrying one end of a piece of furniture, is itself a masterpiece.

Davison is a former Greenwich Village resident who started his nonprofit career in the 1970s at Hamilton-Madison House settlement house on the Lower East Side. He now lives in Connecticut.

There was a time, not long ago, when 124 West Houston St. was gutted, and revealed in all of its original glory, with a “For Rent” sign.

I recalled a great story by Lucian Truscott IV, the Village Voice columnist who’d written about once living upstairs, and hearing Dylan working on “Idiot Wind” on an upright piano which was set up against the wall, on the other side of the building’s staircase. There’s also a great photo of Dylan carrying a little drum, and walking nearby, along Houston St. in front of the window which still has the wrought iron gates. This made particular sense to me, because when I met Dylan, he was walking in the street, and not on the sidewalk.

When 124 Houston was suddenly exhibited with a “For Rent” sign, the bare wooden floors that Bob had trod upon as he toiled to create “New Morning” were revealed to any casual passerby, as was the original tin ceiling and the old broken plaster walls. Here was the bare-bones original, revealed like an old shipwreck that had been washed up in a storm. I was so moved by the sight of it that I found myself regaling a group of tourists about exactly what they were looking at.

I imagine that the front of the studio was closed off to the street in 1970, but now there was only a large plate-glass front, and I vowed to go over there with a camera, when the light was just right, and photograph Dylan’s bare studio. I even wondered if Bob himself ought to be informed that his studio was for rent!

Perhaps he came roving by, late one night, and looked through the window at his Greenwich Village past.

Alas, I never got around to it, and, as far as I know, Bob never came back. Like many a found city treasure, it suddenly disappeared.

Bob Dylan’s original studio was rented, and completely altered by something called New York Pilates. The new enterprise dropped a ceiling and installed some fancy lighting beneath the ancient stamped tin that had once reverberated from an “Idiot Wind,” obliterated the old plaster walls, and they completely tiled over Bob’s roughshod wooden floors. They covered it all over like the proverbial parking lot that paved paradise, and now Bob Dylan’s studio is gone forever.

I’m sure glad that I got to see it, though.

Harry Pincus