BY CHRISTOPHER JOSEPH RYAN | So, I’ve been asked to write a tribute to Irish music legend Shane MacGowan, and — despite the fact that I am far from a qualified potential biographer of his life’s history, and my research abilities can range from “not interested” to “immersed at a level so deep that writing and reflection are nearly impossible” — I shall give it a go.

I personally have never wanted myself pinned, whether under glass with butterflies or under butterfly-like, non-Latin classifications, such as punk, political, traditional, Irish, writer or filmmaker. Still, these labels do find their way to attach to creative folks and they provide perhaps a starting point.

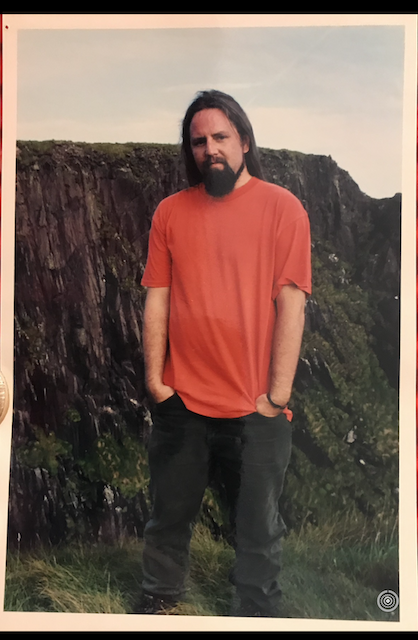

Perhaps I myself have, in fact, come to intersect with Mr. MacGowan in the realms of punk, politics, poetry, Irish descent and shared imperfections in the practice of youthful oral hygiene, although in that lone but important department, I thankfully managed to stay a couple steps ahead of dentally challenged Shane. So, with great humility, decent teeth and a poor outlook on the value of supplemental research, I shall do my best to shed some light on the life of Mr. MacGowan, or at least its relevance to mine, and pull a tribute out of mo thóin* — a.k.a. my ass.

(*A bit of Irish sourced from the original name of Shane’s infamous band The Pogues, shortened from their first moniker, póg mo thóin, which means “kiss my arse” in the Irish tongue.)

Music, like language and history, too, sometimes requires a conscious and organized effort in order to be kept alive. The Irish language — which my young daughter has taken upon herself to learn here in NYC via apps and meetups — was made a school requirement in Ireland back when I first found myself hitchhiking the soggy green fields barely out of my teens myself. Back then, I was only vaguely aware there might be a language beyond some choice surviving expressions people stateside often refer to as being in Gaelic.

There’s a new app…

Now, decades later, due to a school app being downloaded without my knowledge on my migraine-inducing pocket screen, I find cartoon owls Catholic-guilting me into taking “a few minutes each day” to learn Irish — the language that I am sure entire generations of Irish schoolkids wished never existed, but probably value as they become adults. I know I would never find the discipline, except that any activity a daughter wants to share with her dad had better be seized upon in these last two years before the teens. Perhaps it will lead to a future father-daughter trip to the land of fairies, Pogues and Dubliners.

It was a land — a world — that I had to navigate and discover alone and without maps, save for a handwritten list of ancestors, dates and counties, a couple albums of Pogues songs in my memory, and the kindness of those who stopped and gave me a ride by tiny car, lorry or carriage several decades ago, and several times since as a musician myself.

From what I’ve pieced together, my grandparents, and certainly their parents before them, were of the generations that came to America with the goal of assimilating as Americans. There may have been a quiet pride, but no romanticizing, no disposable income for visiting and certainly no Old World music of any sort filling the rooms of our modest homes. Perhaps they saw those songs as old hat, stifling, setting one up for a predictable identity. Not unlike how my kids, and every generation of kids before them, look upon their parents’ music — as a representation and reflection of a culture that one should leave behind and perhaps rise above.

For my ancestors, cultural adherence may be placing one in line for a precinct, firehouse or teacher job — although some, like my father, had other plans in mind for his uncarved road and future. Or, even more tragically, my grandparents and great-grandparents might simply have died too young to be able to give me a real depth of knowledge, tradition or reasons. The generations before me did not often live long.

My sole grandmother reaching any age I could have adult conversation with was Grandma Kay. Kay Lee, formerly Ritchie, found the past too painful to talk about. She filled nearly zero passages of the template book we gave her designed to spark memories and stories to pass down the generations. She was a fiercely independent woman who lived well into her 90s. Yet, I only got glimpses into her hardscrabble life as a single mother raising and putting four kids through college on a Queens librarian’s salary.

A borough once covered by farmland, Queens was where all my great-grandparents seemed eventually to land — but only after forays into tenement Harlem, Midtown and the Lower East Side. The Lower East Side is where I continue to live to this day, with no plans to take the plunge to Queens or wherever one nosedives into an immigrant success story nowadays. Yes, I chose to return to the Lower Manhattan Island birthplace of punk and of my father, his father and now my daughters.

Piles of dusty coal

In the 1970s, upon my dad’s return from Vietnam, I was schooled back in Northeast Pennsylvania. Ours was a former coal town with an Irish presence so prevalent that nearby Scranton holds a St. Patrick’s parade only second to NYC in size and infamy. I lived among the piles of discarded coal, formed high school bands, met musicians and troublemakers. The multigenerational locals found it strange that I didn’t even know my basics of traditional Irish tunes, such as “Whiskey in the Jar” and “Irish Rover.”

Yet, despite this lack of culture or history, I found myself upon graduation, strapping on a backpack and instinctively becoming a rover myself. Fulfilling one song’s stereotype, and thankfully not succumbing too often to the more liver-damaging one, I set out on an uncommon journey. Leaving one’s country was not common among my peers or locale, and I was perhaps solely inspired by my lone encouraging film professor’s flippant comment upon my last day in his presence: “Oh, you must go to Europe.”

And so, with nothing better to do I headed to the U.K., a couple hundred bucks in my pocket, 10 months of legal working papers (six months England, four months Ireland) and a hand-copied list of towns, dates and names found in a dusty old family Bible’s front cover. A genealogical journey that, as with all things Irish, involved plenty of music, with unofficial guides going by the names of MacGowan, Rotten, Vicious, Lennon and Lynott.

Punk stomping grounds

Before hitching a ride to Ireland, for a few months I replenished my coffers with various pub jobs and the like in and around the more cosmopolitan London stomping grounds of my beloved Sex Pistols. These included many of the fabled shops and streets later chronicled in Johnny Lydon/Rotten’s book “No Blacks No Irish No Dogs.” The old pub and workplace signage that Lydon used for his book title introduced me to the concept that the Irish were actually considered a put-upon, discriminated against people.

Ignorance may be bliss, and history malleable, but I’ll take no shame in being raised in my most impressionable years with no idea that John F. Kennedy being elected president was once thought “impossible” due to his “Catholic” background. The closest my dad came to mentioning any victimhood was when I used Testors model airplane paint to add a Union Jack on the face of my ’80s boombox. He recommended I “might want to reconsider flying that flag in light of what that country subjected our people to.” It was perhaps the first, if not only, hint of lessons I was left to learn for myself. My father had no interest in dwelling on our family’s not-so-distant past.

He was more concerned with making the most of being a contractor-turned-entrepreneur in his land of opportunity, Pennsylvania. A place where he eventually was able to own and pilot a small, personal Cessna airplane, as a source of pleasure and symbol of success, instead of being afraid or ashamed to simply have nice hubcaps back outside his family’s cramped apartment in Queens.

On the pub trail

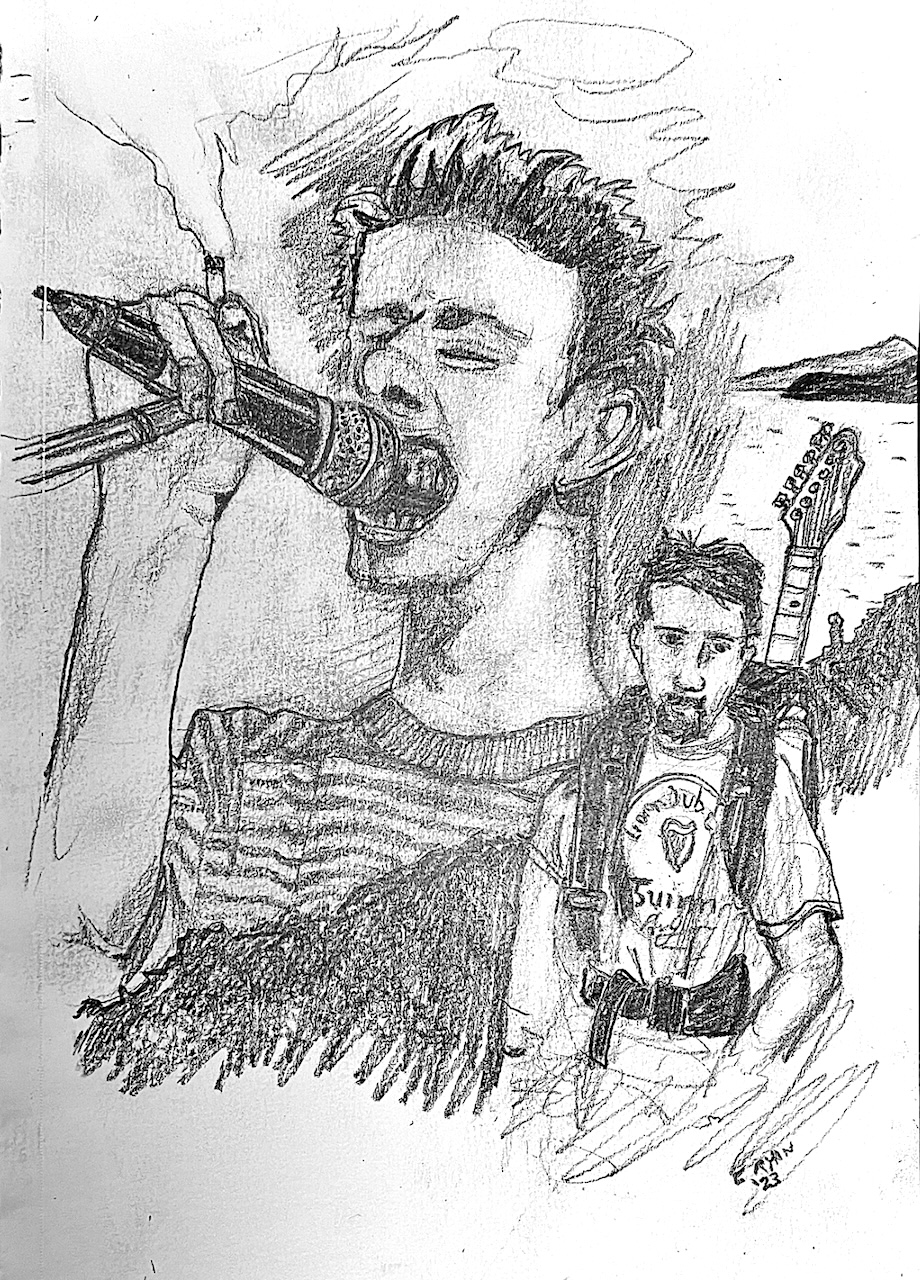

So it was that I found myself a fairly blank slate, guitar on my back, exploring both Dublin and countryside pubs. Pubs that proudly displayed weathered photos of now-sacred moments when The Dubliners graced their non-stages in dusty corners for “sessions.” But what caught my eye in some of the tacked-up or cheaply framed pictures was not the band The Dubliners — either graying in years or their younger, 1960s selves sporting unwieldy beards, fros and sweaters — but the scruffy youngins closer to my age occasionally sharing the stage with these old tin whistle tooters. It was clear the iconic band were tolerating, amused by and unknowingly passing the torch to a new generation. Particularly the least handsome, most punk of them all, a young Shane MacGowan, often hanging off a mic stand and bottle, quite confident for one reason or another that he had every right to grace the stage with these aging legends.

Somehow, despite being a generation apart, the Pogues’ and The Dubliners’ set lists could often overlap. Both groups’ originals could be mistaken for ancient tales due to their themes, language and subjects. Shane MacGowan and the Pogues came of age and began recording in London around the same time as the Clash and the Pistols, etc. Somehow, as those bands carved out a future, Shane and the Pogues managed to fall backward in time from those same stages and shows.

I was told Shane supposedly spent much of his youth in a cabin without running water surrounded by relatives who were rebels, fighters and, as almost everyone seemed to be in rural Ireland, music players of some sort. Perhaps Shane saw the connection of punk to the past, which others did not — perhaps he felt an obligation to bring it forward. Perhaps he didn’t give it much thought at all. But whatever the conscious intentions, MacGowan certainly injected traditional ol’ rebel songs into the art school, working-class and destitute hustler populations crossing paths on the Kings Road in London during the birth days of punk.

Much of The Dubliners’ and even the Pogues’ music struck my untrained ear as a din of almost-too-familiar patterns. But occasionally I’d catch a witty lyric in Shane’s punk snarl and recognize it as equal parts contemporary and traditional a.k.a. timeless. Some of the ear candy that I thought could have been written just a few years back by Social Distortion or the Pistols was actually 100 years old. Some contemporary Pogues originals sounded like they came from rural pub sessions lasting centuries. Sans the vocal-cord gymnastics of so-called rock gods, these young punks, as well as old men, sounded like a rogue gallery of poets, soldiers and farmers who simply had something to say and a medium in which to say it. And in Shane’s case, all traits seemed embodied by a single person.

A wet-behind-the-ears, youthful rucksacker, I tried to keep my equally moist Harmony guitar in tune by ducking into pubs from the eternal rural afternoon “sun showers” that keep Ireland its stereotypical 40 shades of green. One thing that fascinated me was the wide range in age of the denizens of this nearly identical and seemingly endless supply of Irish pubs. There were no old-man bars, or hip young bars. Hell, there apparently wasn’t any daycare, either. See, the age range at any pub (short for “public house,” I eventually realized in a light-bulb moment) ranged from 8 months to 80 years. It was a phenomenon I had never seen in all my days in the commercialized, commodified and seemingly monoculture America I had left in my rearview, and was uncertain of ever returning to.

A culture for the ages

An old guy in a dank, remote pub might stand up and sing a song when the spirit overtook him, and the youngins, closer in age and friskiness to me, would pause their respective dates to respectfully listen. All the while, a little kid might run circles around the legs of all of them, having a splendid time of just starting life. And I suppose that attitude was carried onto the stage and screen when The Dubliners would allow rotting-tooth, young punks like Shane get up with them to sing “Irish Rover” across the airwaves of local television, a song that I found myself living out verse by verse.

Upon my eventual return to the Lower East Side of NYC several years later, I continued my habits of destitute living, squatting basements with drum kits, driving trucks for music-gear money and generally having the time of my life. I was fortunate to see the separated parts of those Dubliners and Pogues in various New York venues, some of which survive today. There’s Paddy Reilly’s, near my great-grandparents’ first honeymoon-days apartment, and Webster Hall, just down a few blocks from my own 11th Street home where I’m raising my two ladies with my activist and politically active wife. There’s also Lincoln Center, where surviving members of The Dubliners would grace the stage with neighbors, such as late-breaking author Frank McCourt, who sat beside me one night.

It seemed that I had gone from illiterate to total immersion, even briefly forming an Irish punk band on Stanton Street with some friends of the NYC punk scene with surnames similar to both my own and my growing, handwritten list of relations. That music project never made it past the rehearsals, perhaps due to other projects of all members going quite well, or perhaps due to our leaning toward playing Bob Marley covers, which might have confused the potential audience or booking agent. Again, a case of our lack of convention and adherence to labels, expectations and identity. Either way, we did not get caught up in the past, but certainly let it fuel our futures. And we certainly enjoyed ourselves, even if little to no tape exists of said sessions. As is usually the case over the organic and analog centuries of friends making music, the memories are sweet.

And now, as a parent, I find myself hauling my little East Village ladies to their music classes. Classes that at first always took place on Sundays, and by chance the commute coincided with “The Thistle & Shamrock” show time slot on the radio. It was an opportunity and reminder I used as a weekly introduction to the arts and culture of “our people,” just so my brood couldn’t say that they, like me, were raised with zero knowledge of any of our history or at least culture. I then would stealthily use some Pogues songs on CD to gently steer the course toward the music I really enjoy — punk and rebel — in hopes some might stick. Either way, at least I myself would selfishly enjoy these educational sessions a tad bit more with Shane’s gruff musings slipping in between the many instrumentals.

Shane’s teeth, Cash 8-tracks…

But, alas, the little ladies seem to mainly be distracted by Shane’s rotting teeth. Perhaps some of the introduction is seeping in, just as my dad may have stealthily done to me and my brother, playing nonstop Johnny Cash 8-tracks. I only learned later that the coal mining songs were often reworked Irish traditional songs from centuries past, and not that dissimilar to the working-class punk songs that can be traced forward to my time, as well.

Well, as it turns out, one of my kids has taken to embracing all things traditional Irish, hence the learning of the Irish language, the arms to the side riverdances and the comforts of the hearty meat and potatoes diet. Meanwhile, the other daughter rejects them all, telling me she doesn’t think she “is Irish at all.” To which I replied, “Then you are the most stereotypical of them all, the Irish rebel.”

I suppose it’s all an exercise in identity. Technology, such as the creepy and strange data-gathering phenomenon, like 23andMe, may put you in a box you didn’t imagine, including a jail cell if you leave a bit too much identity at a crime scene. But your own personal mythology may simply be how you see yourself in relation to this world and its easiest-to-digest perceptions and reflections of you.

I am thankful to have had Shane MacGowan be a conduit to the past for me, and to have brought so much adventure, pleasure, soul and enjoyment to my life. Whether as musician, uncompromising personality or storyteller, he has had a lasting impact on my life, as well as artistic output.

Shane infused himself and all that he came from succinctly into everything he did. Who else could get away with nor less create a Christmas song with the opening words “It was Christmas Eve babe, in the drunk tank,” making it an accessible classic for the ages. Another favorite line, which I have paused during playback to make sure my girls catch the genius within, is in the same, now-timely song, where he cries, “I could have been someone” to his dysfunctional lover. And his duet partner, Kirsty MacColl, replies with the choral backing of studio magic angels, “Well, so could anyone.”

Well, Shane, you certainly did become someone. As I said, I will do no outside research for this tribute, so I can’t know if you ever had kids. I suspect not. But through the rogue children of artists, whether they be songs, words or actual, knee-gnawing little pub rats and potential future artists themselves, we all live on. Hopefully touching some lives, hopefully being remembered, while most, most likely… not.

But as the moron-targeting American shampoo bottles remind us, Lather, Rinse, Repeat. There will be more days, more generations and more music to come in this “Groundhog Day,” eternally skipping like a scratched record here on Earth. Maybe we’ll see our heroes and relations once again in some celestial plane. Or maybe we’ll be reborn as a horse, or butterfly, or thriving NYC pizza rat. Either way, perhaps the Internet will survive long enough to keep us all alive for a few more millennia.

In the meantime, let us all enjoy this day. And this season, as the audiophiles wear out our vinyl copies and patience for “Fairytale of New York,” until the next rogue poets and mediums take our place.

RIP, Shane MacGowan.

Suaimhneas Síoraí Air

(Eternal Rest Be Upon Him)

There are a lot of reflections on Shane — in the sense of how he represented a younger, hipper generation connecting with the traditional vibe of Irish culture and music — and how it is a continuum from generation to generation, which is what Chris found that he, too, had tapped into and connected with, and then hopes to pass on to the next youngins, if they will have it.

This is great. I really enjoyed reading it. Thanks for sharing your memories and perspective.

But this seems to be all about you and not Shane? Where are the reflections on Shane?

True. I am sorry to say that I never got the chance to meet Shane, and although I did get to see him live, and enjoyed the hell out of that, the best I can offer here is how he inspired me to take a journey and that I will pass his music and spirit on to the next generation. I recommend a Great Documentary (easily available on YouTube) entitled: IF I SHOULD FALL FROM GRACE WITH GOD, THE SHANE MACGOWAN STORY —— and you can hear his life story from the horse’s mouth, as well as from his parents and wife. Wonderful stuff. Cheers, Chris

Cool, thank you, will ck it out!