BY DASHIELL ALLEN | At a Dec. 9 public forum, community members and local politicians alike got a clearer picture of what it would take to make 5 World Trade Center 100 percent affordable, as well as the roadblocks lying in their way — namely the astronomical cost of nearly $1 billion, according to one state agency.

The forum was held to discuss the possibility of maximizing affordable housing in the last major development at the World Trade Center site.

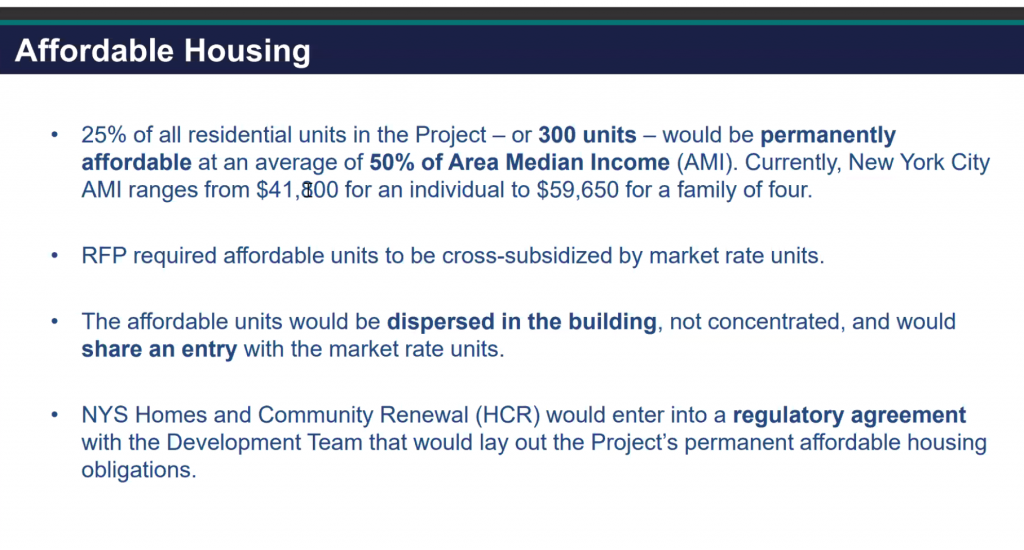

As currently proposed, 25 percent of housing units in the project would be income restricted to families making up to 50 percent of area median income, $53,700 per year for a family of three.

“The current proposal for 5 WTC is a 1,325-unit building with only 330 affordable apartments — we’re pushing for more,” read the official notice distributed by elected officials, including state Senator Brian Kavanagh, City Councilmember Margaret Chin (who was a no-show), Assemblymember Yuh-Line Niou, Congressmember Jerry Nadler and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer.

There was a clear split between the politicians’ modest request for “more” and the Coalition For An Affordable Tower 5’s more ambitious demand for 100 percent affordable housing.

“This is Ground Zero and the eyes of the world are upon it,” said Jill Goodkind, a coalition member whose husband died of a 9/11-related cancer. The Tribeca resident has fought for years for a 100 percent affordable tower.

“We are at an inflection point, where instead of talking about the need for affordable housing we can actually do something about it,” she said. “There’s just one thing that it will take to happen, and that is the will to do it.”

Holly Leicht, the chairperson of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, the agency responsible for developing the 81-story glass tower, had some important revelations. She shared with the public the project’s financial breakdown — revealing vital information that Community Board 1 and politicians have been requesting for months.

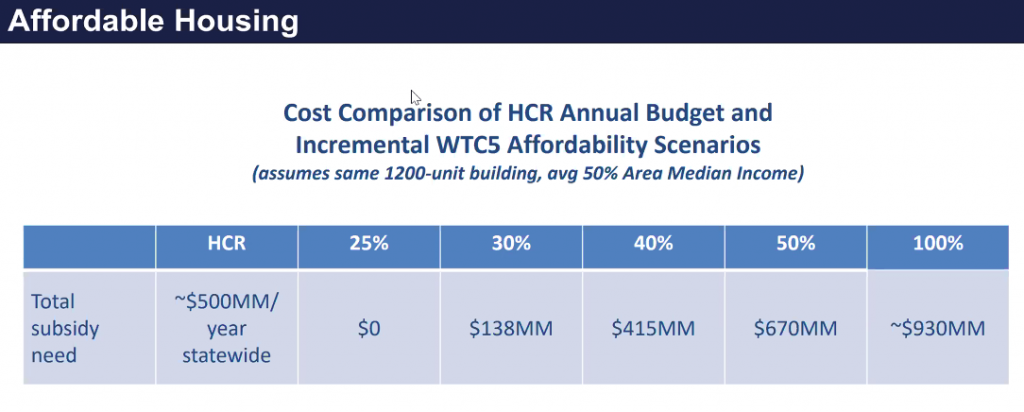

According to Leicht’s estimates, it would take more than $990 million in state housing subsidies to achieve the Tower 5 Coalition’s goals. The coalition sees this project as an opportunity to achieve racial and economic justice in one of the wealthiest and whitest parts of New York City.

“I hear and understand everything that has been said about the importance of this community and the need for affordable housing,” Leicht said. “I don’t disagree.”

Additionally, the Port Authority, which co-owns the lot formerly home to the Deutsche Bank building that the tower would be built on, said it requires $12.5 million in yearly rent revenue to compensate for its “10-year capital plan.”

According to Justin Bernbach, the Port’s director of government and community relations, his agency requires that compensation after doling out billions for the development of a performing arts center and the 9/11 memorial at the W.T.C. site, which could have otherwise been built as revenue-making office buildings.

The state agency representatives did not immediately appear keen on making any drastic changes to their current plan by Brookfield and Silverstein Properties. Although the officials remain in an “open procurement process,” they see their current plan as the only way forward.

“I understand the numbers,” said Borough President Brewer, who appeared resolved to make the project succeed. “But what I haven’t been convinced of is that this city should understand that this is the most important possibility for a major amount of affordable housing.”

She asked to be given a chance “to work with some of the foundations or [explore] other possibilities,” to see if the combination of city and state funding could “come up with something unique.”

Leicht and other representatives did eventually agree to come to the table for more in-depth conversations and “working sessions,” after being asked explicitly by Richard Corman, president of Downtown Independent Democrats.

Leicht also expressed an openness to considering giving priority to 9/11 survivors, defined as anyone who lived or worked below Houston Street or in parts of Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO in the years after the terrorist attack.

Tammy Meltzer, the Community Board 1 chairperson, said of the project, “It can be a model and key for solving diversity issues in our schools, easing congestion on our subways, and help build a base to help support businesses with a robust group of consumers who live here 365 days a year.”

“Even if unintentional, the combination of planning and zoning decisions favoring big real estate and exorbitant rents and housing cost have, in effect, rendered Community Board 1 a segregated community,” said Mariama James, a housing activist and coalition member. She cited Census data showing that, while 24.3 percent of New Yorkers are Black, that number drops to 4 percent in her community board district.

James blasted the current proposal, which calls for three-quarters of the building’s apartments to be luxury, as not meeting the needs of the most marginalized New Yorkers.

“So,” she said, “the question we’re left with is this: Considering Empire State Development Corporation’s widely shared sentiment that affordable housing is too expensive to create here, and in light of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended segregation on public land, understanding that the World Trade Center is in fact public land — up to how much exactly [in] public funds would the Empire Development Corporation…be willing to spend toward integration of this site?”

Coalition members didn’t just make demands, they also offered solutions. Historian Todd Fine listed “a series of financing mechanisms that would not drain existing state or city programs,” including “project-based Section 8 [which was previously proposed for the building by Congressmember Nadler], special federal tax-free bonds similar to the Liberty Bond program,” which financed World War I spending and marked the formation of the Federal Reserve, “501(c)(3) bonds [and] a federal appropriation.”

“And a direct loan from the city or state might only be needed to round things out,” he added.

Fine also pointed out that in the aftermath of 9/11 the government once again issued $8 billion in Liberty Bonds, which, as The New York Times reported in 2006, “benefited developers and high-profile corporations at the expense of ordinary New Yorkers.”

Why couldn’t that type of massive capital spending be made again, only this time to create deeply affordable housing? he asked.

The bonds dolled out post-9/11 created thousands of units of market-rate luxury housing, as well as commercial and office development — including a $1.7 billion giveaway to Goldman Sachs.

No affordable housing, however, was ever produced from those bonds. As one nonprofit official told the Times back then, “All the brilliant minds we have in New York couldn’t find a way to develop housing that would benefit everyone… . Firefighters, police officers and teachers would not be able to afford to live in the market-rate housing built with public subsidies.”

Ultimately, Vittoria Fariello, a Democratic district leader and coalition member, said she was happy with the forum and considered it a success. She said she and many of the other coalition members are excited to get to work with the agencies and find a solution.

I wish there were billions of dollars available for affordable housing development. And it’s absolutely a failure that politicians have found billions and billions for other things but not affordable housing. But given the reactions of all the electeds mentioned here, it sure doesn’t seem like any of them are going to make it happen.

Unfortunately, it seems to me that they are just working with the same local NIMBYs to poison the well against a project that will produce 25% affordable housing with no subsidy, which, if their opposition to the project is successful, will result in zero housing being built, affordable or otherwise.