BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | A Chelsea figure skater needs a lift. No, not for a gravity-defying pairs-skating move — but for his own health.

Kenny Moir, a longtime instructor at Sky Rink at Chelsea Piers, has a serious liver condition and is seeking a donor — a live donor, that is, who would only need to give part of his or her liver.

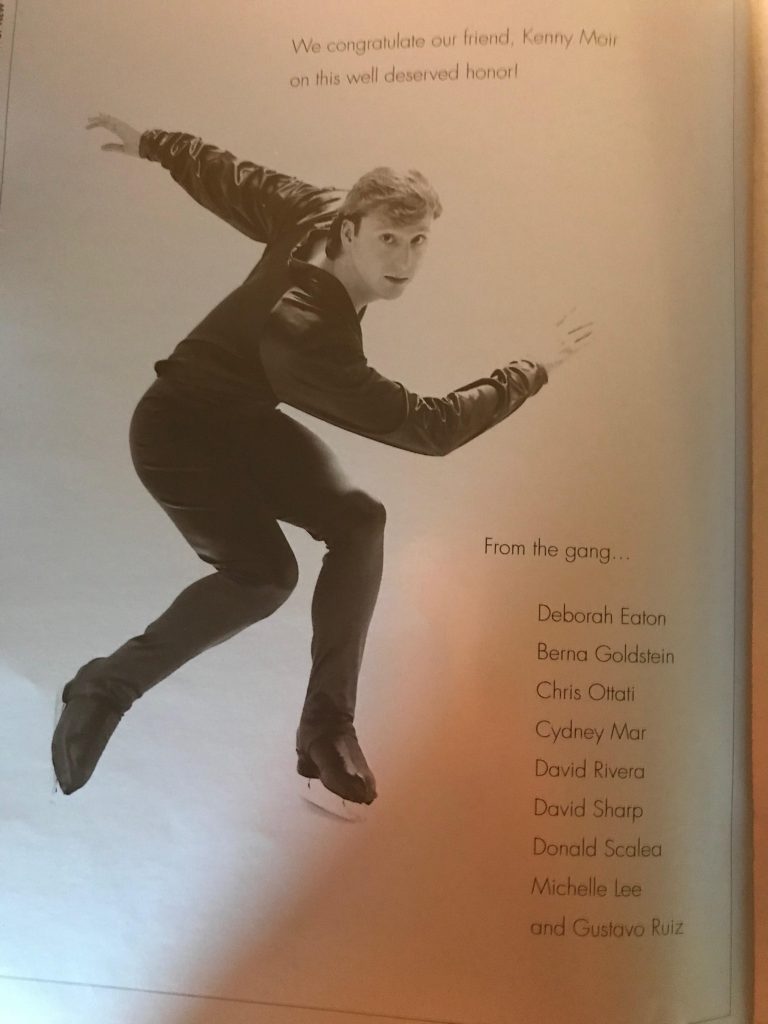

A Vancouver native, Moir, 61, started figure skating at an early age and rose to become Canada’s silver medalist. He never competed in the Olympics because, at that time, the country did not send as many skaters to the Games as it does today.

After leaving competitive skating, he toured in ice shows and moved to New York around 40 years ago to coach the sport, and has been teaching at Sky Rink since 1984. He was formerly the rink’s figure-skating director.

He’s also been president of the Sky Rink Scholarship Board for more than 15 years.

And, on a lighter note, he has what’s said to be the world’s most-viral ice-skating video, with more than 4 million views. In the comic bit — done for the local nonprofit Ice Theatre of New York and filmed at Bryant Park — he starts out looking like he can’t skate for his life, then winds up giving a perfect performance.

About a year and a half ago, though, Moir was suddenly diagnosed with a liver disease known as NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis).

He said he has no idea how he got it.

“It could have been from breathing air from 9/11,” the Chelsea resident said.

Moir has lived in the neighborhood for 21 years and remembers how bad Downtown Manhattan’s air quality was after the 2001 disaster at the World Trade Center.

“I was never a drinker and I ate really well,” he said, “so it’s really a mystery.”

More tough news came last April, when doctors at first thought he had a gallstone, but he was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer in his liver bile duct.

The treatment Moir is hoping to do — using a “living liver donor” — involves a rare procedure.

“Only two hospitals do this — Mt. Sinai and the Mayo Clinic,” he noted.

Obviously, being in New York and not Minnesota, he’s working with Mt. Sinai.

Moir has been getting treatment, but otherwise says he’s in good shape.

“I just went through 25 rounds of radiation,” he said. “It buys me more time to find a donor.”

In addition, every eight weeks, he has to have a stent in his liver bile duct swapped out, which is hard on the body.

Often, the donor comes from one’s own family. But in Moir’s case, that’s not really an option, he said.

“My family is very small and they’re old,” he noted. “My mother offered me a part of her liver, but she’s 97 and I said, ‘Your liver is like tea and marmalade.’”

His sister is also too far on in years to donate her liver. His nephew has the wrong blood type. And he has cousins but they’re either too old or too far away in Canada.

Although the donor would need to give as much as one half of his or her liver, the vital body part would completely regenerate in just four months, Moir explained.

But it can’t be a liver from just anyone. The donor must have the right blood type, a healthy history — no cigarette smoking or diabetes — and no family history that would pose an issue. Moir’s blood type is A positive, so a donor would need to be A positive or A negative or O, which is the universal blood type. The donor must also be within the ages of 18 and 55.

Each potential liver giver must undergo testing to make sure their organ is up to snuff.

A parent of one of Moir’s students volunteered for the procedure, and even though her liver was healthy, it still wasn’t a good match.

“She was 5 feet tall, 100 pounds — she was too small,” so her liver was simply too petite, said Moir, who is 5 feet 9 inches and solidly built.

So far, seven potential donors have been tested and all were eliminated. Two of the potential male donors had fatty livers, “which is apparently becoming an epidemic in New York City,” Moir noted.

“The Sky Rink coaches, many of them signed up [to donate] and either had family histories or had smoked during their youth,” he said. “A friend of mine who hasn’t smoked for the last 10 years, but smoked for 20 years, so was ruled out.”

Donor candidates must go through two days of testing, including an M.R.I. or a CAT scan, and meet with four doctors.

Meanwhile, the doctors Moir is dealing with are “very adamant” that he try to get a family member to volunteer for the procedure.

“Because they’re afraid [otherwise] the person will back out,” he said.

The operation would involve two simultaneous surgeries as the donor’s liver would be partially removed and then transplanted into Moir. It would all be done — believe it or not — laparoscopically, as in, through the belly button, he said.

The veteran skater is holding out hope he’ll find a donor soon. Ideally, he’d like to do the procedure in March so he could recuperate in the spring.

“I’d be off the ice for two to three weeks, then coaching from the side for a while,” he said of how he would recover.

The donor would have to stay in the hospital for four or five days after the surgery, then rest at home about a week and a half before returning to work. If the person does a physical job, such as involving lifting, then another week of recovery would be advised.

Local community activist Marni Halasa, who lives near Hudson Yards, is also a fellow figure-skating instructor at Chelsea Piers’ Sky Rink. In fact, she was first taught by Moir, who helped her hone her blade work on the ice.

“I think why Kenny is so loved is that he really cares about Sky Rink skaters, and always has a compelling vision for the skating community — whether it is how to grow our scholarship fund, how to run our rink’s competitions more efficiently or even how to get a skater to improve on extremely challenging skating skills,” she said.

Halasa worked with Moir as a young coach on her eighth figure-skating test — which she called “the Ph.D. of skating edge work” — and was the last person from the Skating Club of New York to pass the test in 1996.

“I remember Kenny was a driving force in that achievement,” she said. “He would wake me up at 5 a.m. to walk to Chelsea Piers with me to motivate me to skate those dreaded early mornings, as well as push me to excel beyond my own limitations. And that is the same energy he has, even now. He is indispensable to us coaches and skaters and we have to do everything we can do help him.”

Everyone at the rink is pulling for the gracefully gliding icon.

“He’s an integral part of the figure-skating community,” Halasa said. “He’s been around forever. He’s got a wicked sense of humor. And he’s just part of the Sky Rink family. And we all love him.”

People who are interested in being a potential living liver donor for Moir, should contact transplant coordinator Erica Thomas in the Mt. Sinai testing department at Erica.thomas@mountsinai.org and specify that it’s for Kenneth Moir, or contact Moir directly at moirkenneth76@gmail.com .

Be First to Comment