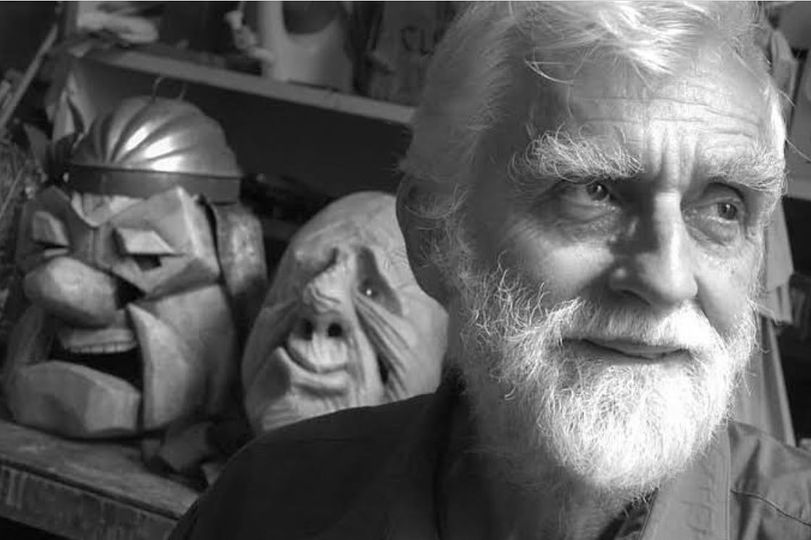

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Ralph Lee, the legendary father of the Greenwich Village Halloween Parade, died Fri., May 12, at Westbeth Artists Housing. He was 87.

Lee was an original tenant of Westbeth, the affordable residential complex for artists at Washington and Bethune Streets in the West Village.

A notice of his passing was posted in the building’s lobby. One also posted on Westbeth’s Facebook page said: “Ralph Lee, Westbeth Master Puppeteer and founder of the Village Halloween Parade and the Mettawee River Theater Company, among many other accomplishments, passed away on May 12, 2023. He was a gentle beloved figure of immense creative vision in the Westbeth community and the world — which is now a lonelier place without him. Our hearts go to his wife Casey and his family.”

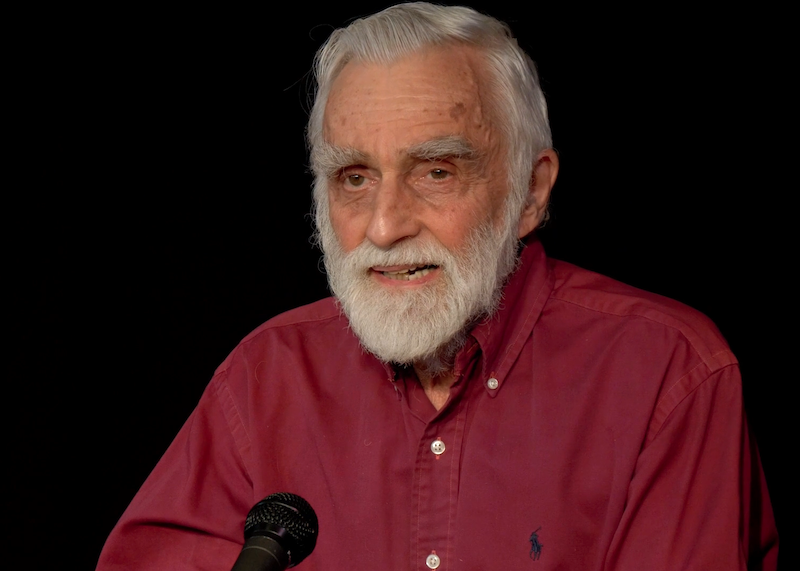

The note referred people to Lee’s Icons profile at Westbeth.org, which features an hour-long video of Lee being interviewed by Terry Stoller, along with friends’ tributes, at Westbeth in March 2018. The Icons program celebrates inspirational senior artists living and working at Westbeth.

Lee moved into Westbeth with his first wife, Stephanie Ratner, and their children — Heather, Jennifer and Josh — in 1970. They were given a large apartment since they had a large family. A theater artist, he would become renowned for designing and using masks and large puppets in performances, most famously the Greenwich Village Halloween Parade.

His interest in theater started very early. He grew up in Middlebury, Vermont, where he attended school in a one-room schoolhouse. As a young boy, after his parents brought back some small Pinocchio puppets from a trip to New York, he started making his own hand puppets and putting on shows. Another creative influence, his mother taught modern dance at Middlebury College, where his father was the dean of male students.

After graduating from Amherst College, Lee did a two-year Fulbright Scholarship in Europe, studying dance and acting. He returned to New York, starting out as a stage actor in small roles on Broadway and Off Broadway, while also moving into set and production design and mask and puppet making, including at La MaMa.

Then, in 1974, he launched the first Greenwich Village Halloween Parade, going on to serve as its director for 12 years. The parade started out as a quaint, neighborhood affair, wending through the Village’s streets. From those humble community roots, it morphed into the massive, boisterous, annual event that it is today, attracting tens of thousands of spectators and participants and televised coverage.

Lee taught at more than half a dozen colleges over his career, including Bennington and New York University. It was at Bennington where he organized his first outdoor performance, which planted the seed for the creation of the Greenwich Village Halloween Parade.

“It was the first time I saw my stuff outside,” Lee said in the Westbeth interview. “It was so much stronger than when it was in an artificial setting. It was just amazing to me. I just decided then and there that I wanted to do my stuff outdoors.”

Lee would later marry Casey Compton, one of his former students at Bennington. They had one child together, Dorothy Lee.

In an interview with Jerry Tallmer in October 2007, Lee described the first Greenwich Village Halloween Parade. He said he was also partly inspired because his children didn’t have “any very satisfactory way” to celebrate the holiday:

“I created — let’s see — a half-dozen or more giant puppets I’d made for other situations. That was the backbone,” he said. “Plus around a hundred masks. George [Bartenieff] and Crystal [Field, both of Theater for the New City] were the producing agents for this event. [Several years later the TNC and the Halloween Parade went their separate ways.] It started at 6 p.m. at Jane Street and went through the courtyard here at Westbeth and then cut diagonally through the West Village, ending up at Washington Square. The idea was a parade for families, kids, straights, gays, everybody.”

There were, he recalls, about 200 people in the parade itself, and many more looking on — a number that would balloon through the years, once television got into the act, to what Lee estimates to be 200,000 annual participants and/or onlookers.

In short order, kids in schools would be making puppets of their own: “The School of Visual Arts came up with some amazing things. We began to get steel bands, Dixieland bands, samba bands, Chinese dancers. We had very good relations with the police. They said the crime rate in the Village went down during these events. The streets were liberated of vehicles, and the parade floats were pushed or pulled.”

Ralph Lee’s glistening brown eyes darken as he says: “It was my hope that, rather than everybody coming to the Village, they do their own in their own community. We didn’t need New Jersey or Long Island. But it didn’t happen. Finally the police began to get concerned. They decided to reroute the parade straight up Sixth Avenue. I directed the whole thing for 12 years, and then I quit.”

It got too big for you?

“It got too big for me.”

“I had always imagined it as a community event,” Lee reiterated of the Village parade during his 2018 Westbeth Icons talk. “Suddenly, it was a gargantuan thing. I had insisted that there wouldn’t be any motorized vehicles in the parade. It just had grown so much. So it was time for me to say goodbye to it.”

In the decades following Lee’s departure, Jeanne Fleming has led the Greenwich Village Halloween Parade. The two met as panelists at an Upstate workshop on outdoor performances — which she, too, was involved in at the time — after which she worked with him for a few years before the handoff.

“He really wanted to stop working on the parade earlier than he did,” Fleming said. “I said, ‘Look, I’ll do everything you don’t want to do.’ I took over raising all the money.

“I’m just grateful to him for starting it and giving it to the world — a tramp stamp of epic proportions,” she said. “I’ve devoted my whole life to this thing that he created. It’s been a great ride.”

Although she knew Lee had been in hospice care, she was hoping he’d somehow be able to attend this year’s parade.

“This little thing that he created, it’s been embraced by the world,” she said. “He thought people would do it in other neighborhoods. That was not the way I saw it: I saw it as a stage where the ordinary person could perform for a vast audience.

“It was the Village,” she acknowledged of the event’s start. “Then New York became the Village. And then the world became the Village. People come from all over to see the parade. Of course, we preserved the tradition of puppetry that Ralph started. … Millions of people have walked in his footsteps, in the sense of the parade. … It’s not the little Village, it’s the tribe — because we make a village that night. People come together.”

Fleming noted she had just gotten a call from Duran Duran, the New Wavers of ’80s fame, who will be releasing a Halloween-themed album on Oct. 27. They’re keen on rocking this year’s parade.

Lee’s daughter Dorothy said, “He was always very appreciative that the parade continued on under Jeanne’s leadership. He would periodically wander through the festivities incognito over the years to soak in some of its energy; it was just no longer the kind of event he wanted to lead himself when it was at that scale. The quote he gave when he stepped down in 1985 was, ‘The parade has always been a celebration of the individual imagination in all its infinite variety. It continues to provide a framework for this expression and invites the participation of everyone.'”

Although Lee moved on from the Greenwich Village parade, he was an artist in residence at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, where he would do smaller-scale Halloween events.

Two years after launching the Village Halloween Parade, Lee became head of the Mettawee River Theatre Company, which puts on outdoor productions based on folklore, creation myths and legends. For more than 40 years, Mettawee produced around 25 shows each summer, mainly in Upstate New York and New England.

“I feel like I’ve been very lucky,” he said in the 2018 interview. “For me, it’s really been important to do theater outside the conventional theater. You get a different audience, people who haven’t seen theater hardly at all. Most of the people we perform for in Upstate New York, they don’t see any other theater. It’s been a real gift to be able to do that.”

At various points, his puppets were also featured at the Bronx Zoo for Easter celebrations, in Washington, D.C., on the Fourth of July, and at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx for Halloween.

At home at Westbeth, he curated a rotating array of his fantastical puppets in an unused guard booth in the complex’s courtyard.

Speaking at Lee’s 2018 Westbeth Icons tribute, Tom Marion, who worked with Lee on numerous productions and “decades of parades and Halloween walks,” fondly recalled being at the Mettawee farmhouse and his mentor’s dedication to his craft and enjoyment of working with his hands.

“The best thing about working for Ralph is working with Ralph Lee, the hardest-working man in theater,” he said. “During rehearsals the cast goes to bed after dinner, but Ralph goes back to his studio to keep working. And when we’d wake up, Ralph’s already risen, working since dawn — more masks, more puppets, design the sets, sketch, mold, paint… .

“But hard work is part of Ralph’s nature,” Marion said. He noted how Lee would drill by hand if there was no electricity, calling it “more satisfying.”

“Yankee through and through, I’ve known Ralph to spend a day off cutting the grass with a 19th-century…scythe,” Marion recalled.

Poet Bob Holman remembered walking into what he called Lee’s apartment “menagerie” as a young poet in his 20s, as a member of the short-lived CETA Artists Project for underemployed artists. His job: “To be the scribe of the Village Halloween Parade.” His newsletter’s name, Pig Beast Speaks, was inspired by the Two-Headed Pig Beast, one of the giant, stitched-together puppets crammed into Lee’s apartment.

The parade had started just a few years before.

“That was another time,” Holman recalled, launching into a vivid description. “That was when the Village felt like a village. … And we’d set off through the winding streets of the neighborhood. But as the parade passed, lights inside the buildings would flash, creatures would appear at the doors and the windows, moons were dancing on the roofs, a giant spider crawled up the clocktower at the Jefferson Market Library, there was a snake on the street sign — I saw it! It was if the city itself had come madly to life, mutated into a twilight ‘Twilight Zone,’ art blending into the cityscape, until you couldn’t tell what was planned and what was improvised. But behind the masks you could tell that this was a completely mixed crowd: gay, straight, young, old, all the races, everybody out, everybody celebrating. … Ralph Lee created the set, the ambiance, the possibilities, so that the city could take a night off and dance.”

However, Holman noted that by 1986 the parade “had grown too large to wander down Jane Street” anymore and instead had to start on Sixth Avenue.

“The parade committee was approached by corporate sponsors,” he related. “Licensing deals were in the air. And Ralph handed on the parade, with no thought of recompense or proprietary continuance. Making product is not what he does — making art is.

“And now,” he quipped, “the Mettawee company marches in the Fourth of July parade in Salem, New York…precisely in the middle of nowhere.”

Fleming, though, said there were never any licensing agreements. She did say, however, that some sponsors were very concerned about the early parades being “too gay.”

“Of course, for years, the parade was so gay,” she said, “and that worried sponsors. And that changed now that we have Gay Pride [the Pride March].”

Friends and neighbors posted tributes to Ralph Lee on Westbeth’s Facebook page:

“An icon. What a gifted artist,” wrote Krista Alderson. “I’m so grateful for how his art shaped the Halloween parades in particular. He created a whole world in those parades. May he rest in beauty and in peace.”

“A GREAT artist and a GREAT human being,” posted Nancy Gabor.

“A literal pillar of Westbeth,” Ethan Maile said. “All us ‘kids’ owe him so much for all the wonders (and the parade).”

“We all loved him so much, and he did so much for our community, gave us so much joy,” Peter Urkowitz wrote. “Rest peacefully, Ralph Lee, you will never be forgotten.”

Ralph Lee is survived by his wife, Casey Compton, and his four children, plus six grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Memorial plans have not yet been confirmed. Those who would like to make a tribute donation are welcome to do so either to the Agricultural Stewardship Association or Mettawee River Theatre Co.

Attending my first-ever Village Halloween Parade, I was legitimately overwhelmed by the pervasive, transformative energy that surged through the neighborhood. Any vista might host an unanticipated creature; spiders climbed on fire escapes, crones loomed out of doorways as the gargantuan figures lumbered past. One moment I’ll never forget — bending down to tie my shoelace, I looked up at the people around me, suddenly unable to distinguish between parade participants and spectators — it was as though we were all, one way or another, in costume. This is the powerful merriment Ralph Lee was capable of conjuring up. Farewell, Ralph, may fantasy guide you, and may magic ever be at your side.

“When the curtain rises on “Plains Daybreak,” one of Erick Hawkins’s most beautiful dance works, there are no dancers onstage. And yet one can hardly call the stage bare, so strong is the sense of activity about to begin. A sleepy bassoon-like sound from an orchestral ensemble signals this awakening. A darkened stage begins to glow with shapes whose initial mystery yields gradually to a universal symbolism. There are two hanging disks and these mobiles by Ralph Lee, it becomes clear, are equated with the sun and moon, ornamented with stars — the sky above an earth symbolized by a bark-like sculptural strip of horizon. The heart of “Plains Daybreak” is poetic distillation of essences. In no time, the stage is filled with figures, or rather with creatures wearing a wondrous series of animal headdresses and masks. One by one, the creatures, dressed in straight tunics, reveal their essences. Mr. Lee’s stylized masks are stunning. No costumes anywhere in the dance world are more original.” — Anna Kisselgoff, “The New York Times,” 2/9/83

I never knew the Halloween Parade originally started out from Jane Street. Great quote from Bob Holman! I remember my first Halloween in Greenwich Village. It was 1982 and I was encamped at the Waverly Hotel – then called The Earle – a fleabag overlooking Washington Square Park. From my corner window I could see and hear the parade. It was impossible to resist and I soon found myself down in the midst of it. A kind of beautiful, poetic madness! Thanks to the imagination of one artist!

Thank you for highlighting the life of this truly beautiful person, Ralph Lee! ❤️

Thanks for this celebration of the life of an artist who is part of our Downtown history, Lincoln. I’m glad to see Crystal Field and George Bartenieff of Theater for the New City mentioned as instrumental to the founding of the Village Halloween Parade. As “producing agents” and also lifelong theater artists, they are an integral part of the performative magic of the initial Village Halloween Parades. Theater for the New City’s role in the Halloween Parade has gone on uninterrupted through the years. By staying open as a space for community creativity against all odds, TNC’s annual Halloween Ball provides a Village destination a few minutes’ walk from the Parade route, where paraders continue their revels — on the open street with bands and the medieval “Red & Black Masque,” as well as indoors in a 4-theater ringed circus of dozens and dozens of macabre live performances in every discipline and spooky interactive experiences surrounded by mammoth puppets and local artists’ murals painted fresh every year. All this culminates in an intercultural big-band dance party in TNC’s Johnson Theater, one of the largest indoor public spaces downtown, where the most eccentric and innovative homemade costumes of the Village Halloween Parade “compete” for weird prizes like “Most Anarchistic” and “Most Banana Puddingish” before the community and celebrity judges like Rome Neal, Miguel Maldonado, and Bina Sharif. TNC’s annual Halloween Ball extends the Village Halloween Parade in its original form: there’s something for everyone, and everyone can get involved. Ralph Lee and TNC’s collaboration have made Halloween New York’s best holiday. Rest in peace and art, Ralph Lee.

George [Bartenieff] and Crystal [Field, both of Theater for the New City] were the producing agents for this event. [Several years later the TNC and the Halloween Parade went their separate ways.] Why did this happen? Do you know? Not sure why most of this is about TNC’s event complete with their “celebrity judges” and says almost nothing about Ralph Lee? This extremely long comment seems like an ad for the TNC event instead of info on the Halloween Parade godfather?

RIP, Ralph Lee. As a young child in the Village in the early years of the parade, you created something really special for us. Thank you.