BY DAVID MULKINS | The Bowery Alliance of Neighbors stands in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, the nonviolent protests over the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, and the efforts to end systemic racism and bias against Blacks and other minorities, both in police departments and other institutions entrusted to serve all the American people.

We also abhor and condemn the violence and destruction carried out in our city by looters, fringe elements and agents provocateurs, all of whom discredit a just cause and bring additional trauma to a city already devastated by the sickness, death, mass unemployment and financial ruin brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

African Americans have endured hundreds of years of slavery; another hundred post-Civil War years of segregation, Jim Crow laws and terror; and in the last 50 years since the civil-rights era, varying degrees of de facto segregation, exclusion and systematic bias and racism by the police and other institutions in the North, as well as the South.

Here in liberal New York City, slavery did indeed once exist, and even when it was abolished in New York State, the city’s financial ties to slave traders and Southern cotton plantations made it very divided on the issue, as evidenced by the bloody draft riots of 1863, which saw vicious attacks on Blacks, their homes and their businesses.

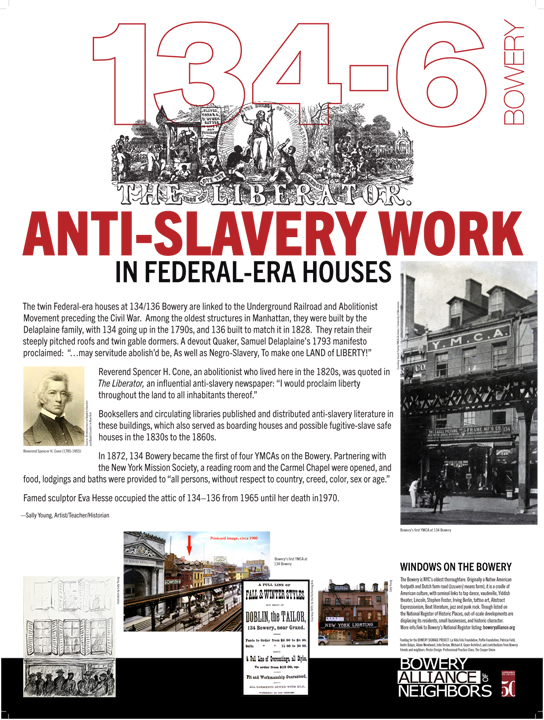

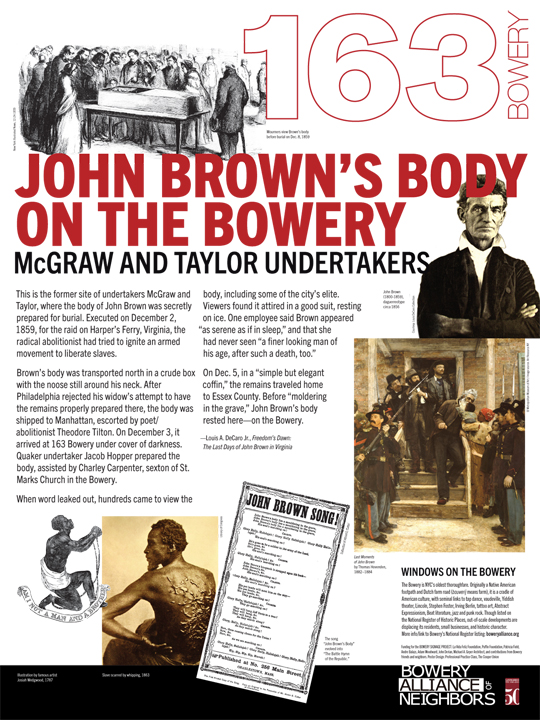

Our recent explorations of Bowery history have highlighted both positive and negative moments of African American history. On the positive end, we are proud to know that Manhattan’s first free Black settlements were on the Bowery, that Nos. 134 and 136 Bowery were active centers of abolitionist work, that anti-slavery fighter John Brown’s body was prepared for burial at 163 Bowery, and that Lincoln made his epochal antislavery speech at Cooper Union.

In 1854, a hundred years before Rosa Parks, on what was once the lower stretch of the Bowery, Elizabeth Jennings, a hardworking African American teacher and church organist, was beaten and thrown off a segregated streetcar. Her victorious legal challenge led to the desegregation of the city’s public transit system.

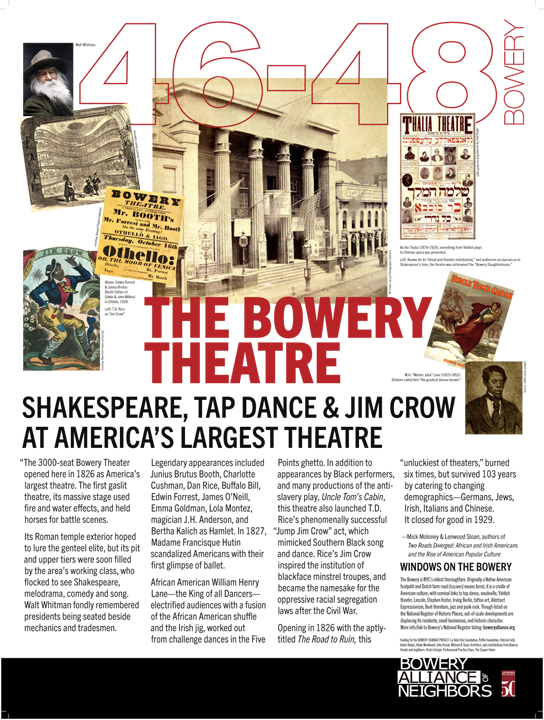

The Bowery was 19th-century New York City’s first entertainment district, and 50 years before Blacks appeared on Broadway stages, they were appearing on Bowery stages. The legendary William Henry “Master Juba” Lane, the African American “father of tap dance,” hit the big time when he appeared at the 3,000-seat Bowery Theatre.

But that same theater also gave a career boost to White performer T.D. Rice, whose “Jump Jim Crow” act — which mimicked Black singing, dancing and joke-telling tradition — helped codify stereotypes of Blacks and led to the institution of minstrelsy. Rice’s show inadvertently became the post-Civil War namesake for the Jim Crow laws that segregated and oppressed African Americans for more than 100 years.

During South Africa’s transition to democracy after the overthrow of the apartheid system, one extraordinarily healing measure was its Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in which victims of human-rights abuses gave testimony, as did many perpetrators of that violence and oppression.

Seeing police officers taking a knee with protesters is a welcome, moving gesture on the individual level that we hope will be followed up by transformative gestures from within the police departments themselves.

The current massive uprising of protest and heated dialogue on race and police bias is extraordinary and will hopefully lead to continued soul searching and truth-telling. Most importantly, it will hopefully result in major institutional change in both police departments and other institutions that impact and matter to the lives of Blacks, other minorities and all Americans.

Mulkins is president, Bowery Alliance of Neighbors.

Thank you for publishing the great article “Racial justice and black history on the Bowery,” including the wonderful representative posters. Hopefully, these efforts will have some effect in promoting racial equality and justice in this country.