BY ALEX EBRAHIMI | “Hello, Greenwich.” That’s what you hear when you call Greenwich Locksmiths. As if the Village itself is picking up the phone.

“Hello, good morning, good afternoon… . I guess it just depends,” Philip Mortillaro told me when I met him on a warm spring afternoon. Standing at the pulpit of his 125-square-foot key temple there on Seventh Avenue South. Blue eyes matching the denim jeans. Metallic beard matching both trade and tenure.

“Now, what do you want to know?” he asked.

Before I could tell him, the phone rang. This time he answered: “Good afternoon, Greenwich.”

On the phone: “No, no… Greenwich Village… New York City… that’s right…”

Hanging up, he told me it happens now and then: “Lady calling from Connecticut,” he laughed. “Soon as I heard ‘locked out of the pool house’… .

“Anyway, what do you want to know?”

“Well, what happened to your first shop?”

Hello, Pacific Northwest

In the early ’70s the locksmith was in his early 20s. The long beard a long way away. Just a couple years into his lease over at his first shop on Union Square and the landlord bought him out.

“Jimi Hendrix, The Doors,” he recalled of his musical soundtrack back then. “But I used to listen to that country stuff, too.”

To paraphrase Hank Williams: “He was just a lad, nearly 22, neither good nor bad, just a kid with 25 thousand in cash.”

He says he wasn’t exactly lost, as the rest of the song goes. But it was the early ’70s. Naturally, he bought a Volkswagen van and started out.

“I knew what I was doing.”

The days meant driving. The nights meant motels. If he couldn’t find a motel, $6 meant camping in national parks. If he needed any money, the fliers at the student centers meant help wanted.

And he knew where he was going.

He knows both sides of the Cascade Mountains range. The east, where it’s as dry as the Mojave — and he’s been there, too. The west, where, when he wasn’t busy cracking safes for the government, he was cracking oyster shells on the shores of the Puget Sound.

Eight years of traveling back and forth from sea to shining sea. Cracking safes like shells. Cutting keys like butter. Wherever he dropped anchor, he opened shop after shop. Washington State to New England and back to New York again.

St. Augustine said, “Our hearts are restless till they rest in thee.” Mortillaro might be restless, but even where he rests, he’s working.

In 1980, he dropped anchor down on Seven Avenue South. The landlord was either tired of renting to a family of fortune tellers or just plain tired of renting. He asked for 40 thousand Mortillaro countered successfully with 20.

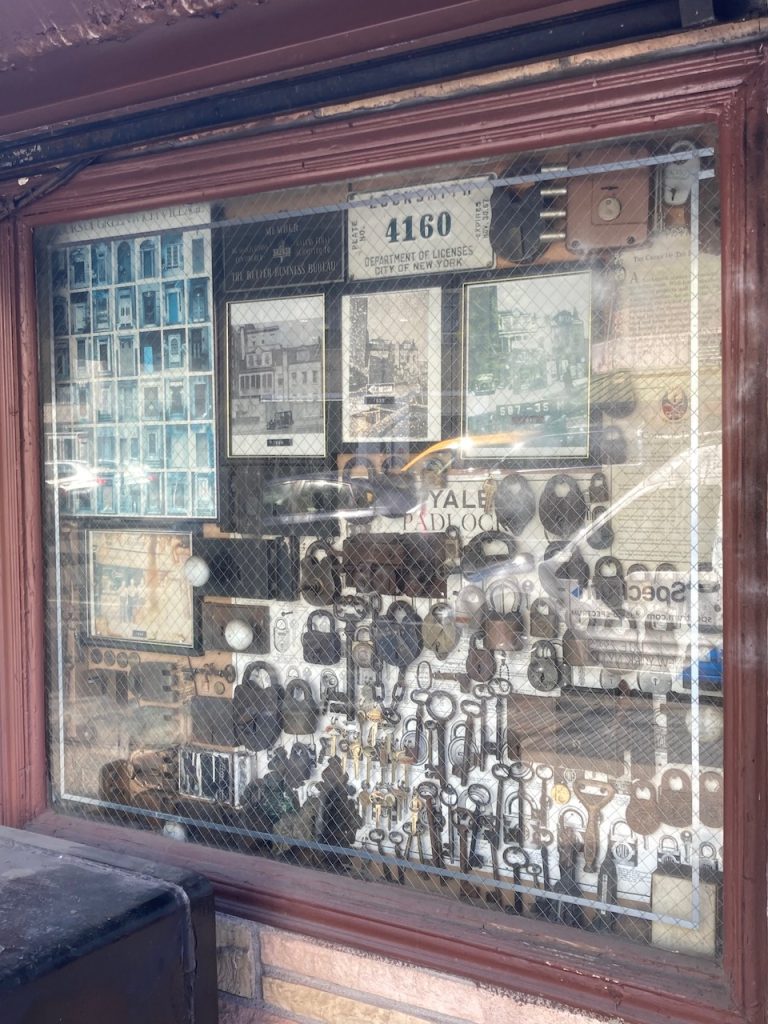

The windows of Greenwich Locksmiths are filled with Americana à la Mortillaro: antique locks and keys and press clippings about the best “box man” both west and east of the Pecos. And at the small door, a relief sculpture of a key that caught the curious eye of a kid walking home from school with his father.

Soon his curious eyes adjusted. Like seeing one star in the sky and realizing there’s a galaxy looking back. Namely, the Van Gogh-inspired facade of starry, starry keys. The kid couldn’t look away. Eyes 125 square feet wide. Smiling like hell but couldn’t speak.

His father was impatient.

“Don’t overlook, don’t overlook,” he said.

They disappeared down the Seventh Avenue throng.

Mortillaro pointed to the relief sculpture of the key on the door.

“Made that when I was 17,” he smiled.

Hello, Vietnam

Down where Lady Liberty’s masses huddled around Lower Manhattan, Mortillaro’s father, a Sicilian immigrant, dreamed like the rest of them: for his son to graduate college and work at Con Edison. It helps if you go to high school.

As a kid, Mortillaro’s probably been to the principal’s office more than he’s been to class. He’s heard it all before. How he’ll be left back again. How he’s not going to graduate.

Playing hooky for kid Mortillaro wasn’t strictly going to the movies: “What did I care about school? I was busy doing night work,” he told me. “I was on the paper route when I was 12. Selling papers. Selling subscriptions. Keeping a register.”

When Mortillaro was 14, he already had hundreds of dollars in his pocket. And by then, he was introduced to locksmithing working a summer job at Reimer Locksmiths uptown. Reimer might’ve introduced him to the trade. Mortillaro fell in love with her.

In ’69, he was back in the principal’s office. What the principal had to say, young Mortillaro hadn’t heard before. But everybody his age saw it coming. Maybe just not everybody in his eighth grade class.

“The way you’re going,” the principal told him, “forget about being held back again. They’re going to draft you.”

“Well, I won’t be in Canada,” kid Mortillaro retorted. “I’ll stay in the eighth grade till the war’s over!”

Cutting keys comes down to a thousandth of an inch. That’s what it came down to for his birthday to beat the lottery.

“My sisters were really worried,” he told me when the phone rang again.

He picked up: “Good afternoon —”

The shepherd of a tourist flock appeared and announced: “And here we have Greenwich Locksmiths… .”

Mortillaro waved as if animatronic as he talked to a customer on the phone. The sun broke through bright and harsh. Smoke from a homeless man blew in black and mild. Andy Warhols passing by dressed more like Randy Warhols. Tulips bowing to the carbon monoxide. Springtime in the Village.

Mortillaro hung up the phone and looked around and said, “A lot of people on the earth.”

“A lot of tourists in the Village,” I said back.

“Well, everything changes. You realize that when you get old.”

“What about Seventh Avenue South?”

“That’s been changing ever since they cut through this town in 1914 to build it.”

He then pointed to where two gas stations used to flank Greenwich Locksmiths. Pointing across the street to the bygone shops of the bygone old-timers.

“That building behind me sold for 11 million,” he said.

The tourist flock pointing to the old-timer and his shop Greenwich Locksmiths moved right along to the next attraction.

Hello, Chase Bank

“Five hundred thousand… no thanks,” Mortillaro said when they called about buying his shop not too long ago.

“Seven hundred fifty thousand…,” he shook his head.

“Then a lawyer calls me and says, ‘I think they’re crazy but they’re offering 2 million. Why don’t I come down so we can talk this over?’

“I told him, ‘Don’t bother. Don’t waste your time.’

“Look,” he said, as he picked up and put down all kinds of tools around him, “money’s just a tool. What the hell am I going to do with it? It’s all about finding your purpose.

“Some of my wealthiest friends are the unhappiest. You can’t take the stuff with you when you die. And why would you? Might complicate things.”

“Did you tell that to the lawyer?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said.

“What happened?”

“Can’t please everybody all the time.”

Great story!

Interesting guy. There’s a father and son. Both Philip. In February 2020 one month before COVID, a neighbor smelled gas coming from my apartment and called the Fire Department, who came and broke down my door. I was just a few blocks away. I came home to find my lock had been smashed. The smell of gas a Con Ed rep said was caused by the burner knob not being perfectly upright. No one would have died but my door suffered the consequences. I called GV Locksmiths in an emergency and they sent someone in 15 minutes. The lock could not be saved. Luckily the repair guy was familiar with the situation and brought a lock and replaced mine; it was a rush job at the end of the day, and I thought they’d come back and fix the lower lock, which was bent. But COVID struck so it had to wait. When I did call in 2022 to schedule the repair no one ever came or called me back. I guess — in keeping with the Philip philosophy — it was deemed not worth it.

Brilliant feature, key tooth sharp!