BY THE VILLAGE SUN | Updated Mon., July 13, 2:30 p.m.: Taking a cue from what artists did last month in Soho, an East Village artist recently spearheaded a similar project to beautify the plywood covering storefronts along the Bowery.

The Soho effort was dubbed #SohoSocialImpact. This one was called @Bringing_Back_Bowery.

Instead of doing the project “guerrilla style,” as she put it, Sono Kuwayama reached out to storefront owners for permission first.

“In the past 100 days, our streets and our lives have changed in myriad ways,” she wrote in a letter to neighbors. “With the recent landscape of plywood, the vibrancy of our history and our neighborhood has also been shuttered. I envision the Bowery and Second Ave. and all the streets in our neighborhood that have been boarded over becoming a beautiful museum or gallery of art — free for the public, which has not had any opportunity to look at art firsthand in over 100 days. Later, these panels might be memorialized, brought together in an exhibition, or saved as a document.”

Most of the artwork pictured in this article is on the still-covered-over windows of the Crunch gym at the northwest corner of Fourth St. and Bowery in what is known as Cooper Square. Gyms have not yet been permitted to reopen.

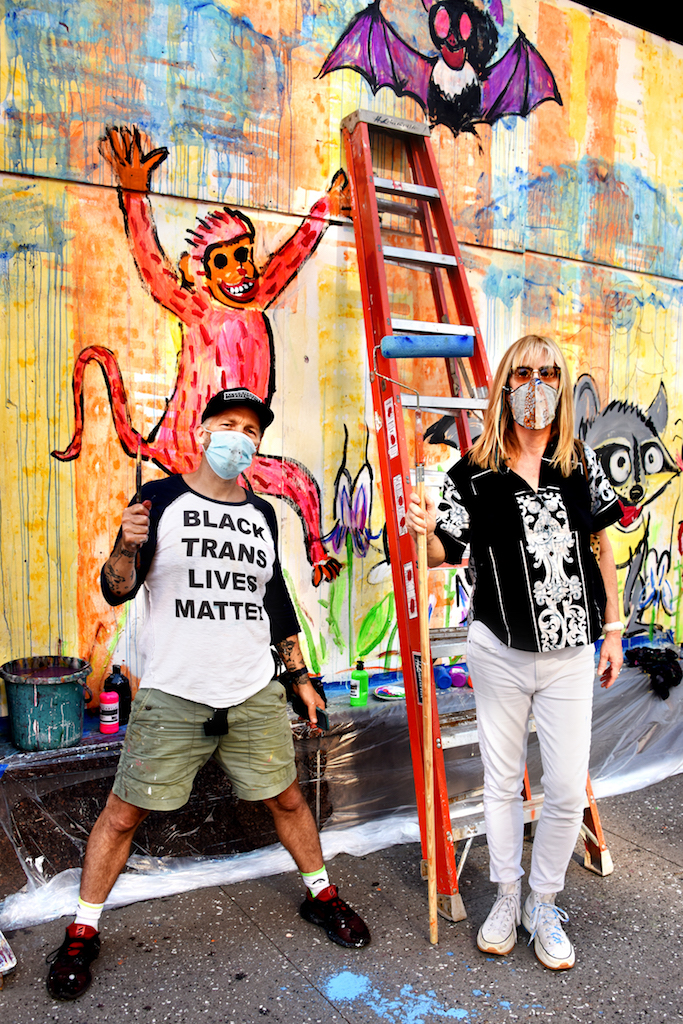

Twenty artists in all gave their time to create the murals. Some of them shared with photographer Bob Krasner their experiences working on the project.

Artists Hitomi Nakamura, Scooter LaForge and James Rubio teamed up on one mural, titled “Love Power.” Rubio started painting the mural at the corner of Bowery and Great Jones St., and LaForge then joined in.

“I was there to watch,” LaForge said, “but then James asked me to paint with him and the mural started to take off and magic was made.

“There are at least 10 layers of paint on that mural. We kept painting over each other’s images and adding onto each other’s images — it was a true mashup.

“At first, Hitomi was very shy with the paintbrush,” LaForge related. “I encouraged her to paint bigger and all over the wall, as she was just painting a little flower in the corner on the bottom left.

“The message ‘Love Power’ and a whole mural came together by intuition. The mural was painted very sporadically and I am so proud of it. Thank you, James and Hitomi, for making a dream team.”

“Painting in public is like a performance,” said Nakamura. “It’s like when I am on stage drumming: Everyone can feel my beat. I want to paint the whole town pastel to make people feel a little better. I saw some dry plants and dry flowers on the Bowery and that makes me sad, makes me depressed. Nobody had given them water in two months and stores were all closed. I wanna see more colors like pink, like Sono’s painting of the pink rose at Adore Floral on Bond St. — that makes me a little happier than the boards over the windows and the ‘F’ word graffiti.”

“Painting now feels like total freedom,” Rubio said. “This country has been rocked by COVID. No in-person shopping, no dining, rampant unemployment. And maybe we needed this pause to finally bring some attention to the racial inequality that had become the status quo.

“Finally without distractions, we are forced to deal with the problems inside our society. Having the privilege to paint on boards put in place to prevent looting also comes with a big responsibility. This country is in need of reform and healing. We need to remember the power of love. We also need to remember happiness.

“That is why I called Scooter LaForge when I found out about this project,” Rubio said. “Scooter is always working from his colorful heart. We decided to title the piece ‘Love Power’ and feature Sponge Bob, who recently came out of the closet.

“This work is about positivity without taking the conversation away from the atrocities against the black and brown community. Love is a natural feeling for us and is the most powerful.”

Rubio also did another painting called “Happy Go Lucky,” which he called “a homage to some of my favorite artists, Walt Disney, Barbara Kruger and Ray Kroc.”

Ava Newley, 16, who painted a “cute alien boy,” challenged herself by embracing a street style.

“This piece is pretty typical of my work — he’s a cute alien boy,” she said of her piece. “But whatever the viewer sees is equally significant to any label I can ascribe.

“It’s easier for me to let pieces develop themselves instead of branching off of preexisting ideas, so I’m just letting it paint itself,” she noted. “I’m trying to emulate more of a street style, which is different from the cartoon realism that usually trends in my artwork.

“I’m focusing more on geometric perspective, as well as using a colored outline alongside the black ink, which is a theme I picked up from graffiti lettering. Working big on the boards was a fun challenge for me, and I loved meeting the other artists! I hope I can provide some eye candy to any passerby.”

Her mother, Angela Tassoni, used a golden skin tone in her piece because it “represents all skin colors as one…there is no black or white,” she said. “There is only the skin that we all share, in it together as one.”

In recent years, she’s been focusing on making sustainable jewelry, and her Tassoni Jewelry company has mostly monopolized of her time.

“I had planned to start up painting again this August,” she said. “This project has given me a jump start to August and it has been an an adventure. I’m enjoying spending time doing what I love with my daughter Ava alongside, as well.”

Catt Caulley painted a portrait of Trayvon Martin.

“I paint for equality,” she said. “I paint for all. But, most of all, I paint for the seen that had been unseen during their time — the ones that had been overlooked and condemned for differences beyond their control. Their story was so short but they left a print on our history and in our lives.”

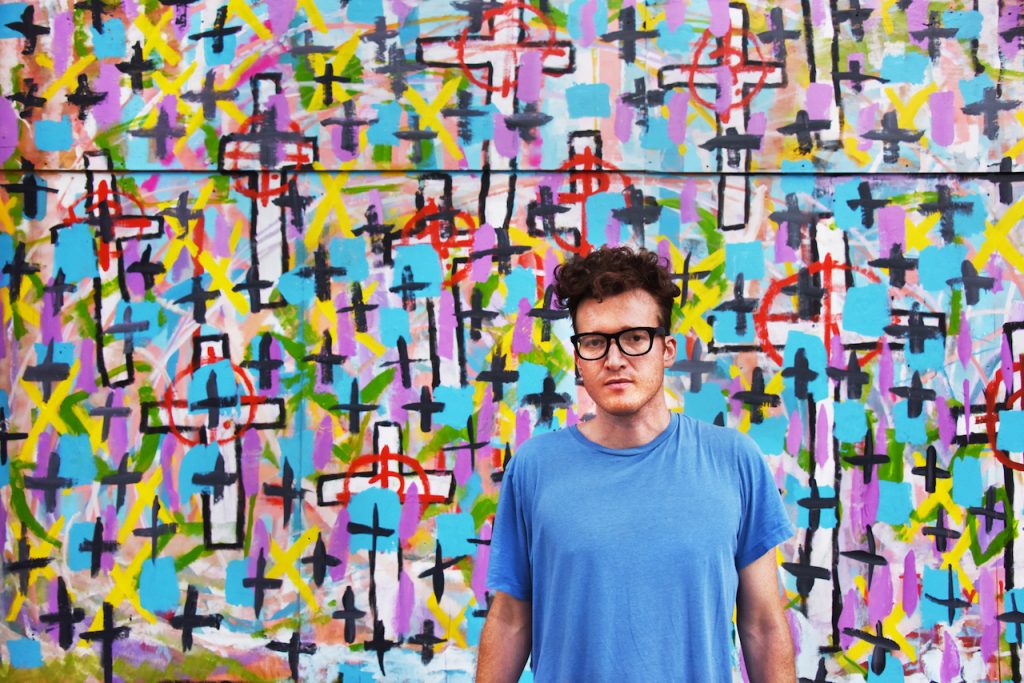

Robert Blodgett, in his artist’s statement, explained his focus on shapes and patterns and also the healing aspect of religion.

“Much of my work involves the repetition of simple shapes and patterns,” he said. “The cross, for me, represents Jesus’ emphasis that we love one another. The white crosses, as they form, also conjure images of tombstones for those counted, uncounted and countless black lives that have been taken from us.

Irena Kenny said her interest was piqued when she heard about the earlier mural project, in Soho.

“I’ve never worked that big but was intrigued,” she said. “And once I started, it’s been hard to stop! I welcomed Sono’s invitation to paint on the Bowery. More boards! More opportunity to use art to shout out my thoughts through buckets of paint. It’s been a wonderful chance to help unmute the windows of the boarded-up city and utilize art as a tool of social critique.”

She said her piece in Cooper Square was part of the Gay Pride celebration.

“I’ve been thinking about some of the hard-won victories over the past decades,” she said. “In 1973, homosexuality was finally no longer recognized by the American Psychiatric Association as mental illness. In 2015, the Supreme Court said yes to same-sex marriage.

“In this time of upheaval and desperate desire for change,” she noted, “reflecting on these victories gives me hope. And we all need hope right now! So how better to welcome Independence Day than with two serenely intertwined Lady Liberties? The eye says, ‘We see you!’ Can you see them? Love is love.”

Kamila Zmrzla was putting a little heart into her mural.

“This is my sixth mural in the last three weeks — my first on Bowery,” she said. “The rest were, and some still are, in Soho.

“This is called ‘Before the Kiss’ and is reflecting the beauty of love between two men. I want to show that it’s beautiful — the almost a kiss,” she said. “Almost kissing someone, the seconds before, the energy and excitement that flows through the body before physical contact. It’s about love. Love is universal. It’s inspired by Gustav Klimt’s ‘The Kiss.'”

Joining her in painting was her 11-year-old daughter, Nelly Otcasek.

Kuwayama, the project organizer, said, “As the pandemic overtook New York City, I began to miss going to galleries or museums because I’ve found that they are places of refuge for me, places I go to for both comfort, inspiration and, I suppose, artistic nourishment.

“As the looters came through and wrought destruction in the neighborhood, I was at first distraught and frightened. I couldn’t bear to see the boarded-up storefronts because it was so depressing. That was the genesis of the project — a hope to bring the neighborhood back to life and embrace and bring to light the long history of the arts in the area.

“The murals are immediate and their relationship to time and space are different to that of a painting hanging on a wall. They are created in a huge burst of energy. Most of the artists painted their murals in a day or two. This wasn’t sitting in a studio and coming back to something over a long period of time. It is a dynamic way of working.

“There is something very democratic about art in the streets,” she added. “There is no admission fee, there is no preciousness. We were of all ages and genders and races and styles of painting and also experience with painting.

“I have never painted out on the streets before and the streets called for a different expression from me than what I am usually at work with in my studio,” she acknowledged. “It was also an incredible experience to meet the people who live in my community and to interact with the various shop owners and building owners. A sense of community was at the fore and I couldn’t have hoped for anything better.

“Art is a very special thing, touching all people,” Kuwayama said, “a visual language that transcends speech and can reach anyone regardless of age, gender, sexual orientation, race, education, economic status, etc. It’s also nicer to look at than plywood storefronts.”

Also contributing a mural to the project was Mario Gonzalez, Jr., better known as ZORE64 in the graffiti and street art communities worldwide. As opposed to others who contributed pieces, street-style art is not a new experience for him — it’s his passion.

“I grew up during the ’70s and ’80s underground street cultures and am simply here to remind people where this particular art form comes from,” he said. “And giving back to the few people that are still here in these streets and neighborhoods that are now in high demand to the highest bidders.

“I’m not here to decorate the city,” he declared. “I’m here to reclaim our public domain and try and give back to the streets. This here art form comes from worldwide, one city, one ’hood, one country at a time.”

Kamila Zmrzlá is the best.