BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Sending shockwaves through Downtown Manhattan, Mount Sinai has announced it will close Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital — and soon.

The plan is to shutter the historic Gramercy health hub, at 16th Street and First Avenue, in slightly more than a half year from now, on July 12.

Following the loss of St. Vincent’s Hospital in 2010 and Cabrini Hospital in 2008, this would leave Manhattan south of 23rd Street with just one small, 200-bed, full-service hospital, New York-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan, all the way down by City Hall.

Meanwhile, everyone, from local politicians to M.S.B.I. hospital staff and union representatives, claims they were blindsided by the news.

Mount Sinai officials say the health system has been unable to staunch the iconic hospital’s financial bleeding. At this point, they have no intention to build a replacement mini-hospital nearby, as was the plan a few years ago until scrapped due to the need for bed capacity during COVID.

The cost to build a new mini-hospital was $650 million a few years ago but, due to inflation, is now more than $1 billion.

Mount Sinai is not publicly saying yet what it plans to do with the property after the closure, saying the goal right now is just to “ramp down” operations at the hospital. Clearly, though, it would be a highly coveted site for residential development, overlooking the historic, 4-acre Stuyvesant Square Park just to the west.

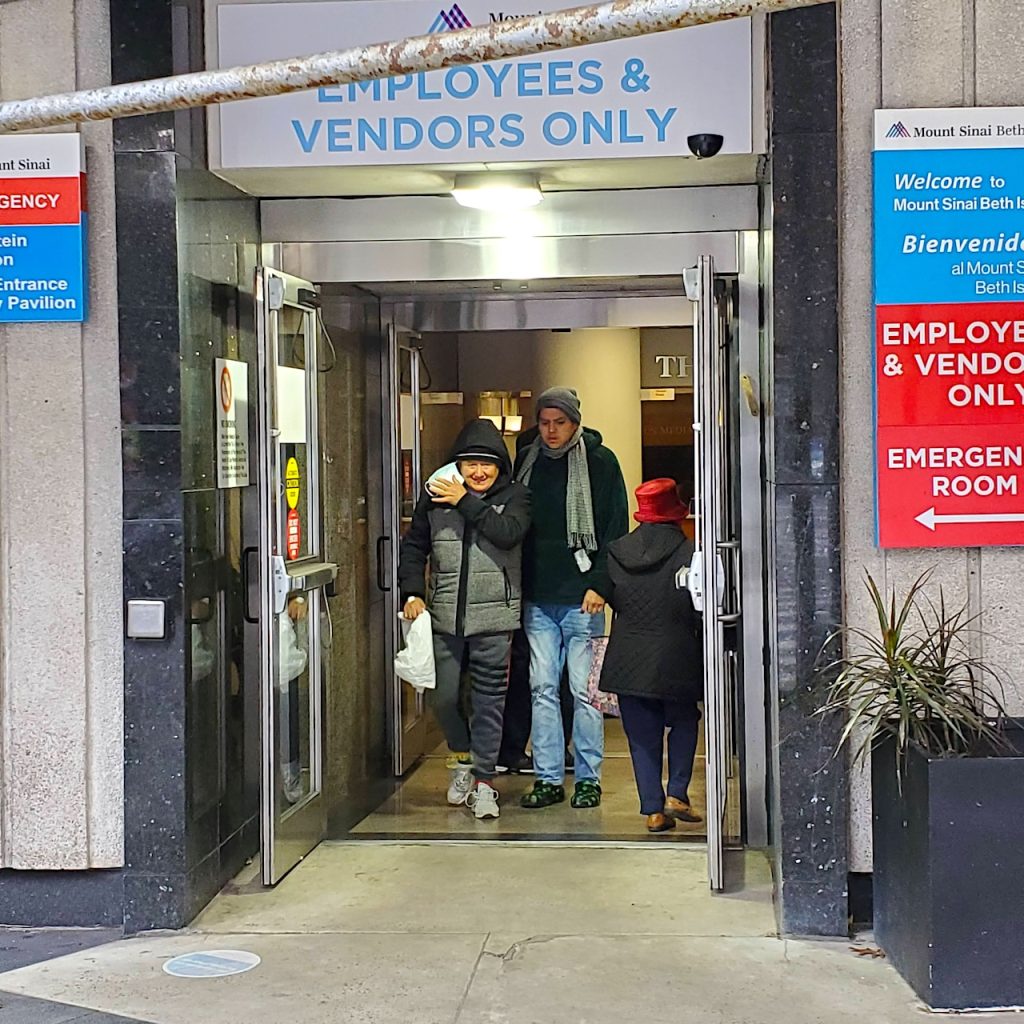

Emotions boiled over at a raucous Nov. 28 public forum about the closure plan at Baruch College. The 175-person auditorium was packed to capacity as a panel of Mount Sinai officials seated on stage laid out why the M.S.B.I. Gramercy campus is simply “too large” and a major cash drain on the health system.

Elizabeth Sellman, president and C.O.O. of M.S.B.I. and Mount Sinai Downtown — a system of health facilities scattered around south of 23rd Street — told the forum the cash-strapped hospital is projected to lose $150 million this year after years of similar losses.

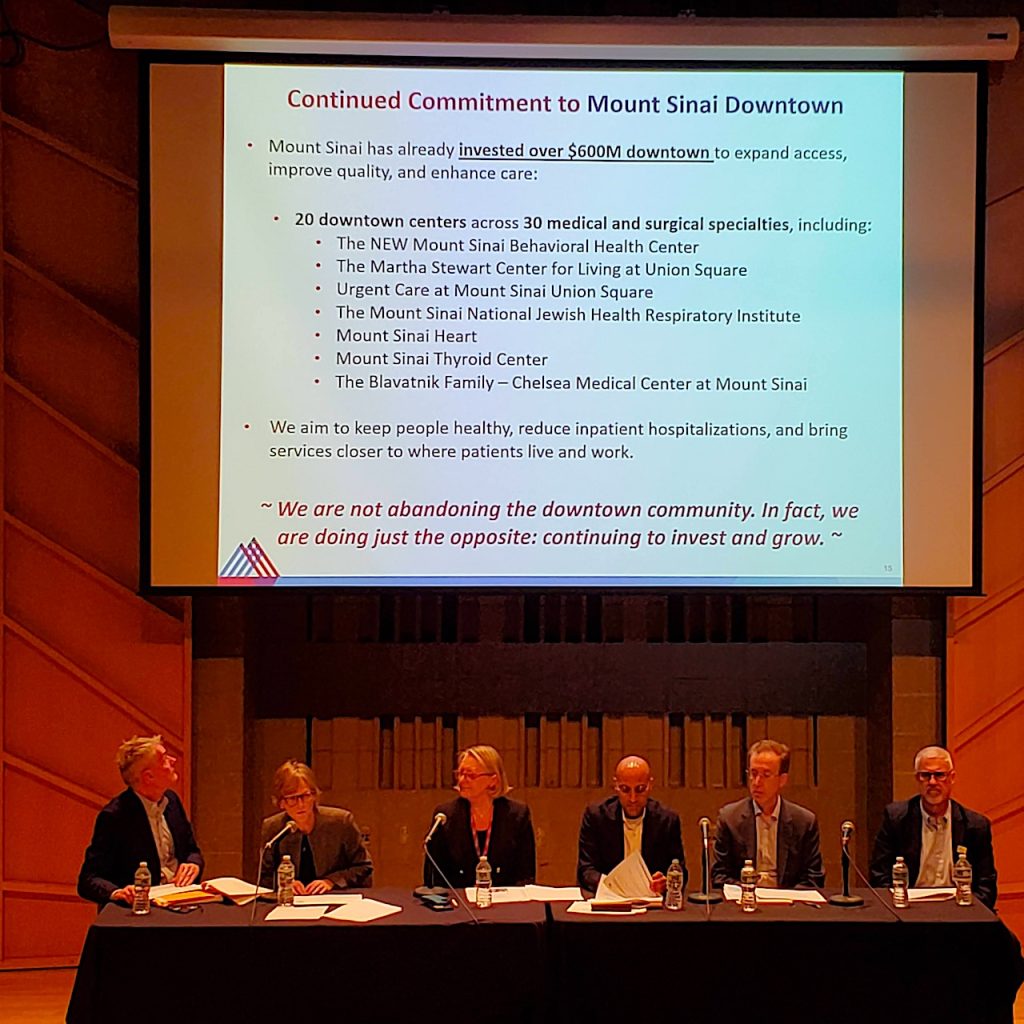

She and the Sinai officials said the health system’s Downtown network — especially its 10 Union Square East location, with comprehensive and urgent care — could pick up the slack after the Gramercy site closes. Mount Sinai has invested $600 million into these sites, they said. Audience members shouted back that the money would have been better invested into the M.S.B.I. Gramercy hospital itself.

There are also 30 urgent-care centers south of 42nd Street, the health executives noted.

Sellman said 85 percent of patients that visit the M.S.B.I. emergency department are treated and released, meaning they don’t recuperate at M.S.B.I. A full-service hospital, it has hundreds of in-patient beds, though currently uses only 100 per a day. She added there are “four other” E.D.’s serving the area. Sellman also noted that around half of the patients that the hospital sees are “from out of the area.”

In short, the C.O.O. said, “We are shifting focus to ambulatory care.”

Yet, Sellman said, M.S.B.I. will keep its E.D. open until July 12, as well as its “med surge” nursing for patients before and after surgery and acute care.

Mount Sinai has in recent years already been relocating medical departments from M.S.B.I. to its Uptown campuses to create “centers of excellence,” as the officials said.

All union staff will be offered jobs at other Sinai locations and the health system will try to reassign nonunion staff, the officials said.

Mount Sinai has submitted a required closure plan to the New York State Department of Health, which must O.K. the plan for it to go forward — though approval has not been granted yet. The 150-page plan is also posted on the health system’s Web site.

Meanwhile, local politicians, in a united front at the forum, objected that they had been left out of the loop, and declared that the E. 16th Street facility must be saved.

Assemblymember Deborah Glick said, if M.S.B.I. closes, people would have to go to Mount Sinai West (formerly Roosevelt Hospital), at W. 59th Street, or Mount Sinai Hospital, north of E. 96th Street, noting, “That’s a schlep for a lot of people, particularly people with few resources.”

Councilmember Carlina Rivera said, “Quite frankly, many of us feel devastated” by the news. “Everyone knows, the closer you are to a hospital, the better you feel [about your health safety].”

Rivera said she’d like M.S.B.I. to become a so-called “safety-net hospital” — meaning get higher reimbursement for Medicaid patients, equaling more funding for the hospital.

But the politicians were indignant to hear the Sinai officials respond that they, in fact, tried working with State D.O.H. over the past two years, in vain, to get safety-net hospital designation — yet never told them about it.

Assemblymember Harvey Epstein, noting his daughter was born at Beth Israel, said, “The lack of transparency here is really troubling. We care about this hospital.

“I don’t like the plan,” he stated, telling the Sinai panel, “We want to work with you to keep it open. There are lots of people in this community, particularly low-income, Section 8 [tenants], who have no other [health] option.”

Councilmember Keith Powers, a lifelong resident of Stuyvesant Town, across First Avenue from M.S.B.I., hoped that at least there could be a stand-alone E.D. and health center, similar to Lenox Health Greenwich Village, which opened on part of the former St. Vincent’s campus in 2014.

“We want to keep something there,” Powers said, though conceding, “We know healthcare is changing.”

Robert Gottheim, Congressmember Jerrold Nadler’s district director, accused Mount Sinai of “dishonesty” in having met with D.O.H. without clueing in local elected officials.

“You spoke to the state for two years and we found out about this two weeks ago,” he accused, also expressing concern about what would happen with the property.

From the back row, a nurse shouted that the former nurses’ high-rise residence north of M.S.B.I. is now a New School University dorm.

Mark Levine, the Manhattan borough president, noted 400,000 people live in Manhattan south of 23rd Street.

“We have been hemorrhaging full-service hospitals in Lower Manhattan,” he said. “We’re down to two.”

Stand-alone E.D.’s are not the same as a full-service hospital, he stressed, noting, “There’s something special about an emergency department and a hospital at the same site.”

L.H.G.V., at 12th Street and Seventh Avenue, actually will be adding hospital beds in the next few years — but not many, only a dozen.

“For people that live in NYCHA developments, people on Medicaid, this is a critical hospital,” Levine emphasized of M.S.B.I. “People are going to default to Bellevue, and Bellevue’s already overcrowded.”

“This affects all of Downtown,” said Councilmember Erik Bottcher, who represents the West Side, including Greenwich Village and Chelsea. “You have every elected official who represents this area united to keep this open — as well as everyone in this room.”

Sellman noted the M.S.B.I. Downtown health network has 20 locations, calling it “very robust and significant,” to which a woman in the audience called out, “Not 24 hours!” meaning none are open round the clock, unlike a full-service hospital.

The forum was then opened to audience questions, many of which were more furious screeds than questions, particularly by nurses and health union members.

One nurse angrily claimed there was “no communication” to alert employees of the forum and asked why it wasn’t being live-streamed, so more people could watch it.

“This is a done deal,” spat East Village activist Barbara Caporale. “You have proven that you don’t give a damn.”

However, District Leader Arthur Schwartz, who previously filed a lawsuit that, he said, slowed down Mount Sinai’s earlier plan to close M.S.B.I., accused that once again — just like before — the health system has been moving ahead with closing the hospital without an O.K. from D.O.H.

“How is it that you’re shutting things down when you’re not approved to?” he asked.

Citing regulations, he quoted, “‘You shall not eliminate services'” without state approval, adding that this “is going to be the basis of [new] litigation” he intends to bring against the health system.

“Where is State Department of Health at this meeting?” Susanna Aaron, the chairperson of the Community Board 2 Human Services Committee, asked disapprovingly.

Mark Rubin, a Westbeth resident, came to the forum straight from work in his scrubs. A former photographer, in 2016 in his mid-50s he became a nurse in the M.S.B.I. intensive care unit, three years after Mount Sinai and Beth Israel merged. He said he had seen the “systematic evisceration of that hospital since Sinai took over.”

Rubin noted often cardiac patients who go to the L.H.G.V. stand-alone E.D. are transferred for higher-level care to M.S.B.I. Without Beth Israel, he warned, “Those patients are gonna die. They’re not gonna make it to other hospitals.”

The Village Sun earlier in the day spoke to a young internal medicine resident getting off his shift at M.S.B.I. He shared that staff had just been told that, within the next three weeks, they would be moved to Mount Sinai West or Mount Sinai Morningside (formerly St. Luke’s). He added that, in another consolidation, the hospital’s cardiac unit had already been merged with its I.C.U.

“It is still very busy,” he said, though adding, “They are closing beds down. But people that were here last year say that it’s less busy, a huge difference.”

A Sinai community affairs rep assured there would be more outreach meetings, with live-streaming, as the closure plan moves forward.

We need hospital space in Lower Manhattan, and the hospitals there certainly need some funding. However, just willy-nilly closing and getting rid of overbuilt hospitals without regard to NYC’s architectural heritage is no solution. Abandoning 24-hour emergency rooms is no solution. While some luxury housing could bring in revenue, I would still like at least some use of the campus area as hospital space, and I would urge any new development avoid demolishing the oldest part of the hospital and the round pavilion on the corner — and that any new development must be a mixed-use site. I also urge NYSDOH to reject the closure plan as is and work for solutions that satisfy all parties (including funding the hospital as is, if that is the avenue the public wants to take).

Councilmember Carlina Rivera said, “Quite frankly, many of us feel devastated” by the news. “Everyone knows, the closer you are to a city park, the better you feel [about your health].”

Oops, silly me, wrong issue!

But seriously – last year I took a really nasty fall in the street and wound up with a whopping case of cellulitis in my right leg – I went to City MD for help, where the doctor took one look at it and told me to go to the Beth Israel ER IMMEDIATELY, because what I needed to have happen (antibiotic IV drip, two venograms in 12 hours to make sure no blood clot was forming, heavy-duty oral medication) was outside the scope of their abilities. Walk-in clinics open certain hours of the day, no matter how many there are, will never make up for having a 24-hour emergency site available.

Another tragic example of when business executives, not medical professionals, are put in charge of medical institutions and value profits and the allure of real estate development windfalls over the medical needs of the community. Shameful; if not downright criminal. St. Vincent’s/Rudin redux.

If you’re going to cite St. Vincent’s, don’t overlook that its ultimate closure followed not one but two bankruptcies; and that the second bankruptcy was accelerated (not provoked but ultimately assured) by short-sighted opposition to St. Vincent’s seeking revenue streams (e.g., revenue from luxury housing) to subsidize its money-losing activities. ‘Money-losing activities’: Yes, there are aspects of medical care – and hospitals – that can be ‘for-profit’; but ‘for profit’ was never St. Vincent’s purpose for existence. Was management of St. Vincent’s less than competent? Yep, that too. But the fatal blow to St. Vincent’s existence was short-sighted opposition to St. Vincent’s proposed sources of revenue – luxury housing. Those opponents have never – to this day – offered a viable business plan for not-for-profit medical care.

Short-sighted planning indeed. The St. Vincent’s/Rudin plan was to put their entire operation into a 32-story, pencil-shaped building to replace what became Lenox Health Greenwich Village on 10% of their land, with no place to grow, as circumstances would most assuredly change, and give Rudin 90% for development.

These are the very same people who justified demolishing several historic buildings on their campus in the ’80s claiming their state-of-the-art, new facilities would last forever and then came back not 20 years later with a plan to demolish those new buildings in favor of the proposed new tower across Seventh Avenue whilst paying consultants and high-priced executives millions of dollars to push their ill-conceived “rescue plan.” The first St. Vincent’s bankruptcy did nothing to extinguish their debt and then went on to take on more.

Those folks and Rudin made out like bandits while the community still suffers its loss.

How about next covid;)?

Do we really have too many hospital beds?