BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Occupy City Hall was not too occupied on early Monday afternoon. In fact, it was pretty empty.

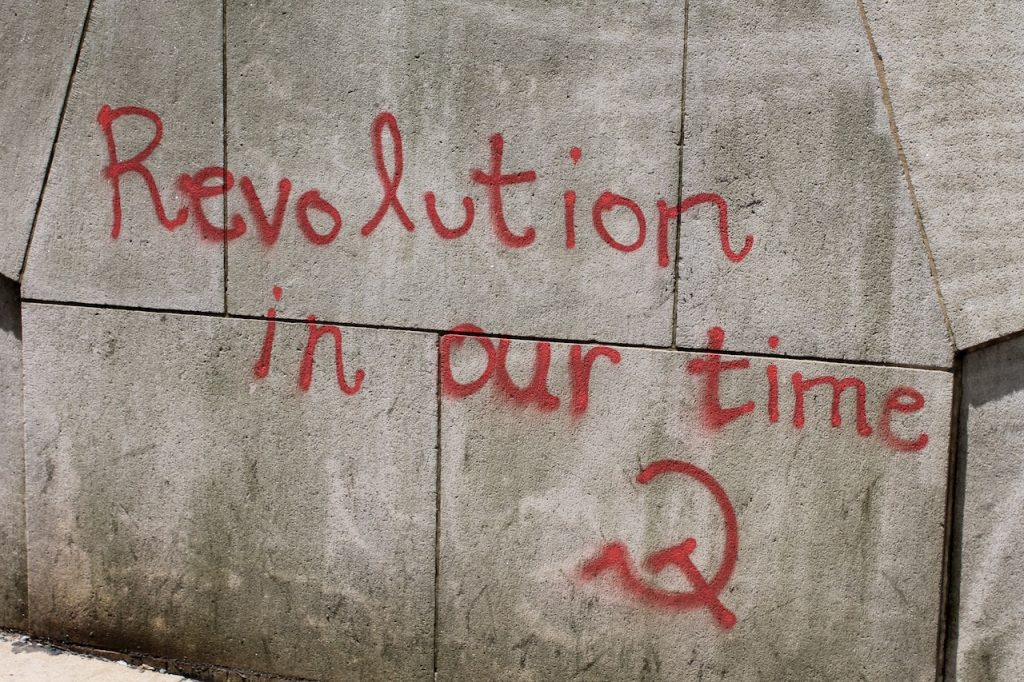

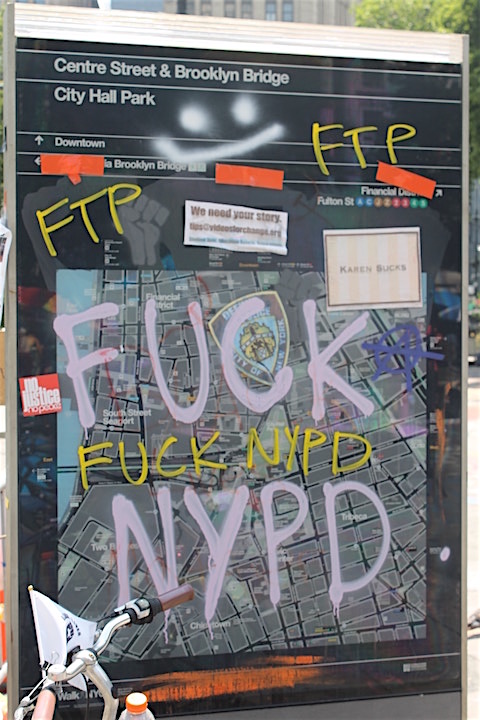

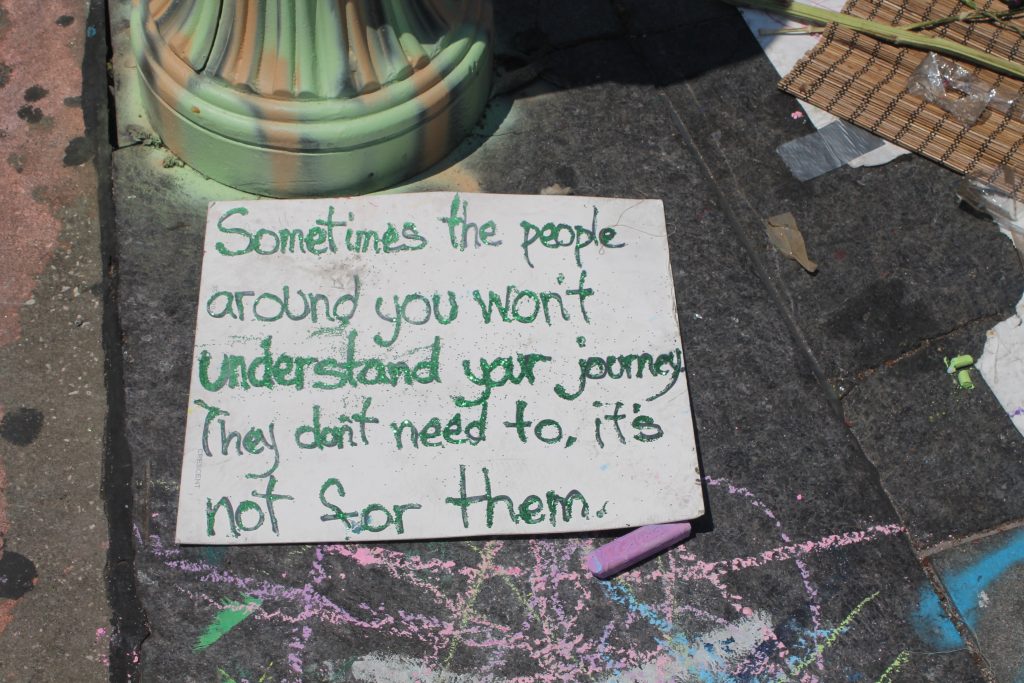

Although every inch of the plaza outside the eastern side of City Hall Park was covered with artwork or graffiti, on the paving, on lampposts, on trash cans — everywhere — there weren’t a ton of people around.

But there were some. They included volunteers dutifully manning tables and dishing out food. Others were lounging in a couple of groups in shady spots — some amid tents on a grass lawn near Chambers St., others sitting around socializing near the entrance to City Hall.

A news film crew was going around doing interviews.

“Things kind of slowed down after the Fourth of July,” said Aidan Hamid, a 26-year-old writer from Brooklyn, who was manning the welcome table.

Several groups that had been involved in leading the effort have departed, including Vocal NY, Warriors in the Garden and Black Lives Matter of Greater New York.

Hamid chalked that up to “leadership wanting to take some R&R. It was well deserved. Some of them had been going 48 hours without sleep.”

The encampment reached its emotional peak on Tues., June 30, as the New York City Council was due to vote on the budget. The Occupiers had demanded that the Council “defund the police” by slashing $1 billion from the Police Department’s budget.

Police clashed with the activists that day, but the Occupiers were able to hold onto their space.

Ultimately, the Council did cut the demanded amount of police funding — but much of that was achieved by merely shifting school safety agents from the Police Department to the Department of Education.

At any rate, Occupiers interviewed on Monday said they plan to continue to commandeer the plaza because there is still more important work left to do.

A young Brooklyn artist, musician and engineer who gave his name as Rogue declared he has never felt more alive and purposeful than he has being involved in this movement.

“I’ve never been happier,” he said. “I was feeling miserable when I was working. Capitalism is zombification, it’s the rat race.”

He said Occupy City Hall is now also known as Abolition Plaza. At its highpoint, it had 500 people, he noted.

“I’m learning every day,” he said, “learning from radical black thought leadership.” He quickly amended that to “radical black feminist thought leadership.”

Asked if they want to keep holding the plaza, he said, “Oh, yeah. This is public land. There’s no reason for us to leave. At the same time, we want to assure we’re keeping the political momentum going, as well.

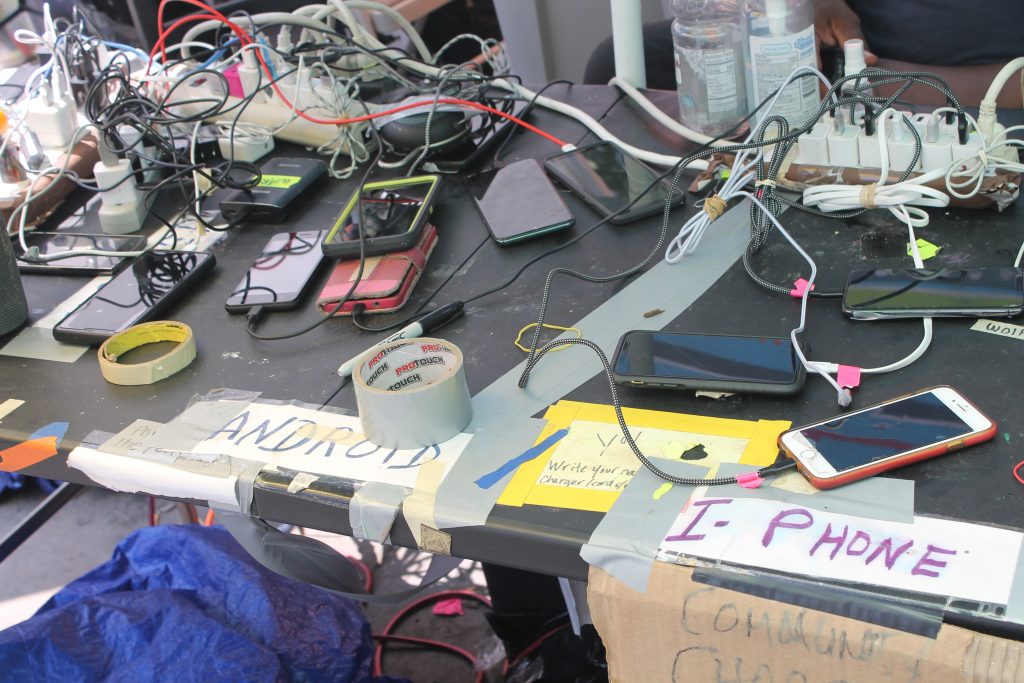

“The U.S. ambassador to Pakistan came to talk to us,” he added. “We have a bodega, a library, a garden.”

Affordable housing is a key issue that the protesters also now want to address, according to Rogue.

“You think the riots were bad, now think what happens if you displace a fifth of the American people,” he warned. “We need to cancel rent.”

He added that people of color would be disproportionately affected if there are mass evictions.

Police had clashed with the protesters twice, he said, though admitted that on Monday into Tuesday it was because the Occupiers tried to take over Centre and Chambers Sts.

“They were trying to beat us because we were in the streets,” he said.

Police then tried to bum-rush the encampment on Wednesday, he said.

As for how they held off the invasion, he said, “It was numbers — and we trained for it prior. We formed human chains.”

Added Hamid, “The night the budget was passed, they tried to clear the space. But we had a really strong organizing vibe. We locked arms in rows of three. There was some pepper spray that was released.”

If people in the first row were pepper-sprayed, the next row would step up, he said.

Hamid said, earlier on, Occupy City Hall used to feature a daily schedule of discussion groups on various topics.

“It created a great space for discussion,” he said, rattling off some of the topics: “how to interact with the police, how to de-escalate, encouraging people to call their councilmembers [on the budget vote], do their own organizing.”

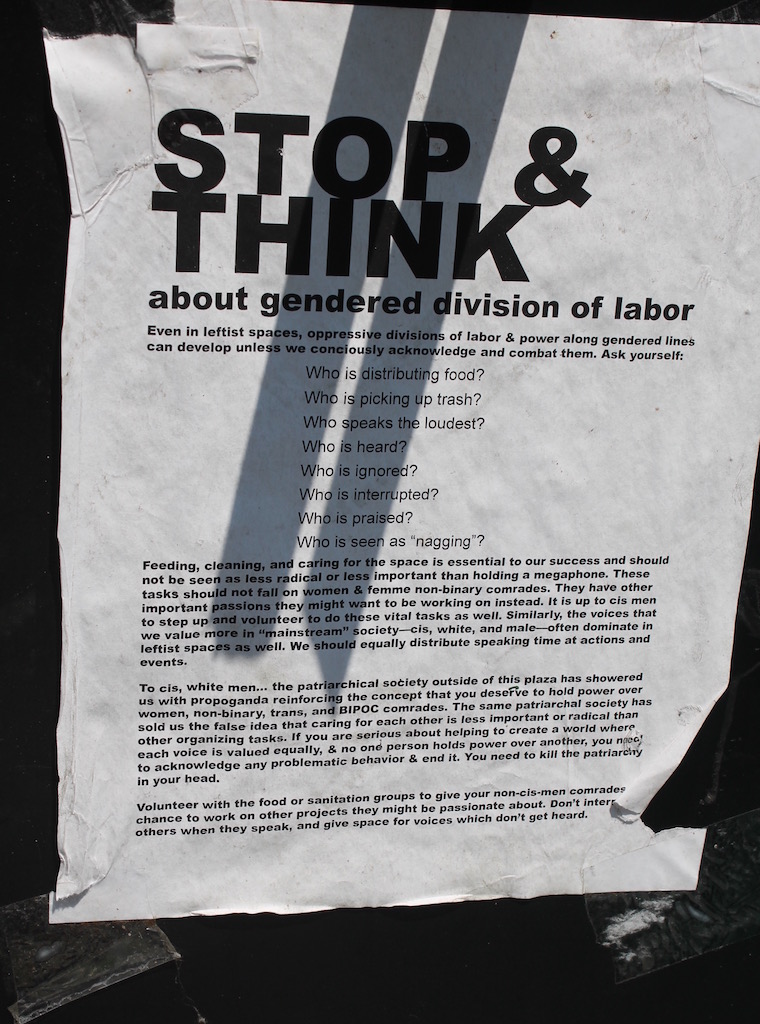

Other discussions focused on internal workings of the encampment, like dealing with unwanted sexual advances.

Some homeless people who came in and “were maybe not in the best mental-health state,” he noted, were directed to a mental-health tent for counseling.

Asked about the impact the experience has had on him personally, Hamid said that, after the 2016 election, he was disenchanted with politics, but the occupation has provided a needed boost.

“It helped me reclaim my political power,” he said.

Hamid, too, emphasized that black women had played a vital role in the struggle.

“Female black leadership was very good at mediation and de-escalation,” he said.

An effort has been made to empower “traditionally disempowered” voices, particularly black women and black transgender women, he said.

Christopher, who only gave his last name, was manning the food table. He said there are definitely more issues to fight on.

“The first goal was getting the bill passed,” he said, apparently referring to the police budget cut. “Now, it’s the abolitionist phase — transitioning incarceration centers into rehabilitation centers.”

A man who gave his name as Hassan B. was using a black marker to add writing to an artwork someone else had drawn on the ground. It was his fourth day at the occupation.

“I see in here, there’s no separation,” he said. “People don’t see color. It’s about ‘how do we make it better?’ I see other people that it didn’t happen to joinin’ in. I recommend them. I do appreciate it.”

By “it,” he meant being racially profiled or treated unfairly by police.

The artwork he picked to add words to featured an eye as its main theme. Continuing the visual theme, he added the lines: “I see murder. I see no justice. I see no future. I see no way out. I see blood. …”

“I experience violence every day,” Hassan said. “Every time I go outside.”

Referring to criminals and police alike, he said, “There’s bad people on both ends — but they always target us.”

He meant that police unfairly suspect and target blacks.

As an example, he recounted a time he made a police complaint and a responding officer mistook him for the crook.

“I had my bike stolen,” he said. “I called police, and I had a gun stuck in my face. … I’ve been stopped so many times driving,” he added, in exasperation.

Hassan, who said he works in fashion, was sporting a baseball-style batting helmet and clear goggles around his neck. But he claimed those weren’t just for Occupy City Hall — that he wears them every day, for protection from police violence.

“I have another one that covers both ears,” he noted, describing an even more protective helmet.

Meanwhile, for one straphanger the occupation went a little too far. Wearing a crocheted face mask with “BLM” stitched onto it, the woman said she needed to use the elevator to get down to the subway platform. But the Occupiers had blocked the entrance to the lift, whether intentionally or just due to all their stuff.

“I have a doctor’s appointment,” she said, with annoyance. “I support the Black Lives movement. But you can’t block the subway. I fractured my ankle, I’m still in a lot of pain.”

Rogue went to check it out but apparently there was nothing to be done, and the woman walked off in frustration.

A couple of hours later, a monsoon rain poured down, cooling things off, but soaking Occupy City Hall.

Meanwhile, the police budget has been cut and police reforms have been passed, but shootings and murders have been skyrocketing in New York City.

On Monday, Police Commissioner Shea reported that during June there was a 130 percent spike in citywide shootings compared to last June (205 versus 89), and a 30 percent increase in murders (39 versus 30).

Burglaries during June also soared, by 118 percent (1,783 versus 817), while auto thefts rose by 51 percent (696 versus 462).

Over all, for the first six months of 2020, the statistics are no less troubling: Year to date, murder in the city is up 23 percent compared to the same period last year (181 versus 147), while shootings are up 46 percent (528 versus 362).

More glorification of violence and vandalism.