BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Officials from New York University and New School University detailed the schools’ fall plans at a meeting of the Community Board 2 Reopening Working Group on Monday.

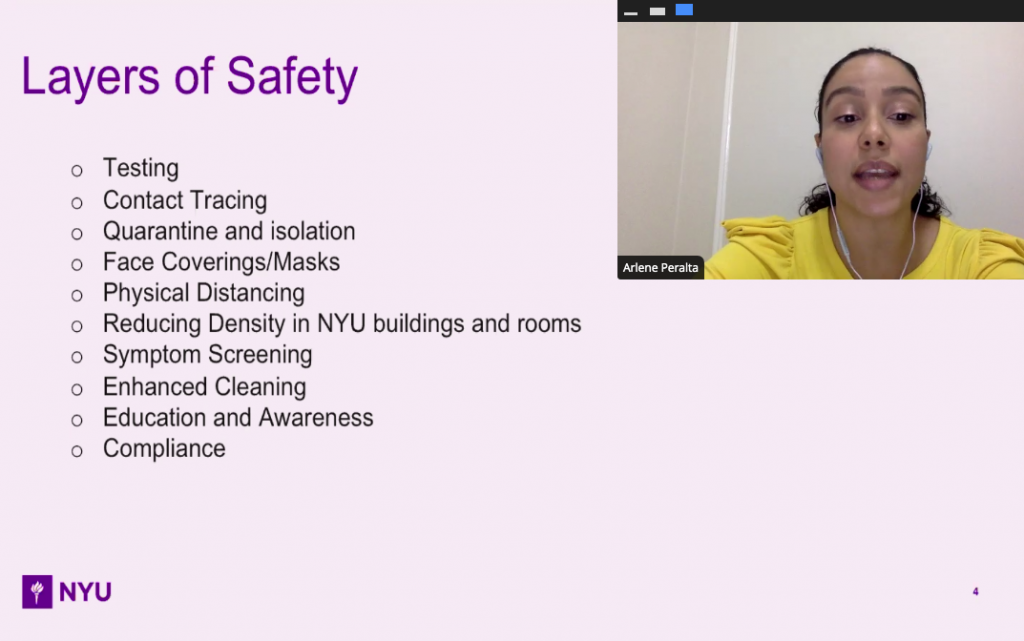

In general, the representatives expressed confidence that the schools have solid health-safety plans in place to deal with the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

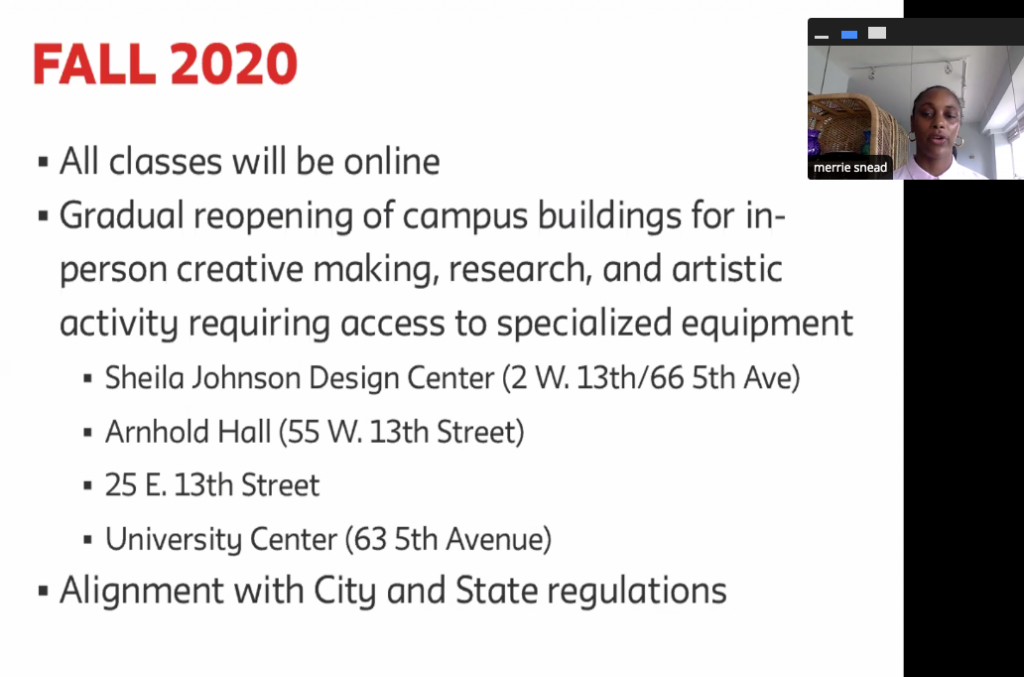

N.Y.U. will be using a so-called “hybrid model,” with half of its classes taught remotely and half in person. The New School, on the other hand, will only have online classes.

N.Y.U.’s residence halls will be housing less than 40 percent their usual occupancy of 11,500 students while classrooms will be at 50 percent capacity. Larger classes will be held remotely, and smaller ones, in person.

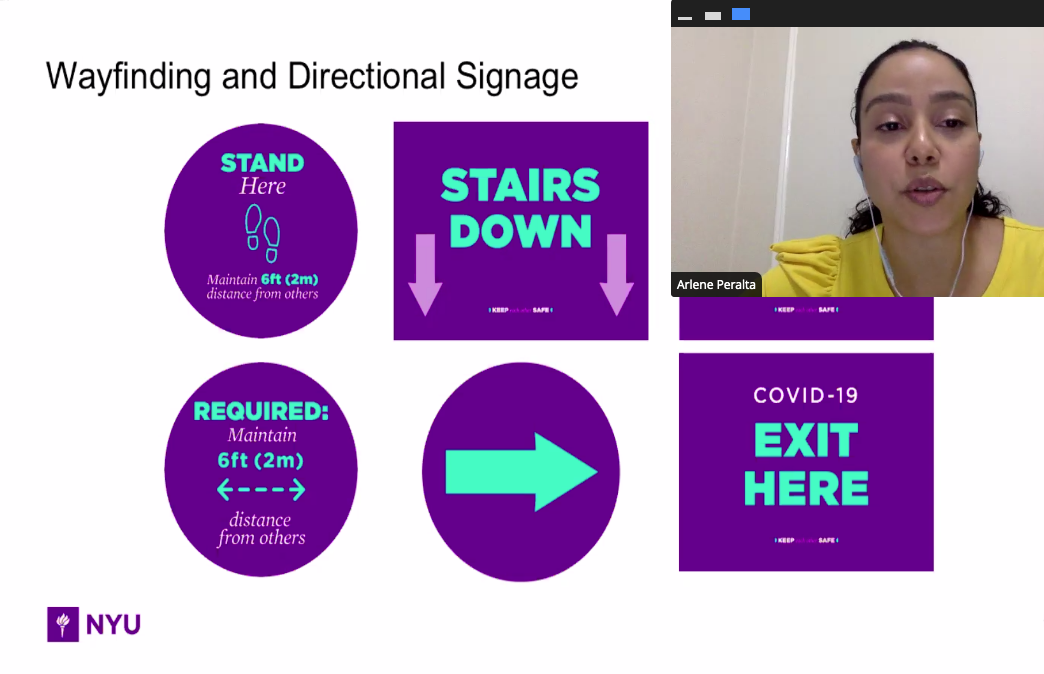

“The key is reducing density across our students, faculty and employees,” said Arlene Peralta, N.Y.U. senior director of community engagement.

Another part of its health strategy, N.Y.U. will have more than 200 “student health ambassadors” who will play a role in ensuring the university adheres to safe practices.

Amy Malsin, New School assistant vice president for communications and public affairs, explained that the New School’s plans were driven by the fact that it’s “a very vertical campus [without] a lot of real estate to spread out.

“Given what we know [about COVID-19], we felt that remote learning is the best approach for us,” she said.

Also, she noted, the fact that “path of the virus is changing” right now makes remote learning the better option.

In addition, the New School has moved to a three-term model for this academic year, which will allow for a “winter intensive” session for students who are planning a “lighter fall,” she noted.

“Spring…will be a much more intensive course for students,” Malsin predicted, adding that next summer will also offer a chance for students to “make up,” as in catch up, on course work.

Merrie Snead, New School communications and community relations manager, and Malsin added that there will only be a small number of students — 160 in all — on campus this fall. All of the students had to quarantine for two weeks before being allowed on campus, Snead noted. They’ll all be staying in Kerrey Hall, in the University Center, at Fifth Ave. and 13th St., which usually houses 600 students.

There will only be one student per suite in Kerrey Hall, and the on-campus students will study and socialize in “small pods,” staying together throughout the trimester.

N.Y.U., meanwhile, starting this week, will be doing “mass testing” of students for COVID in a large tent on its plaza on W. Fourth St. east of Washington Square, said Dr. Carlo Ciotoli, associate vice president of N.Y.U. student health.

Several times, in different ways, board members asked at what point the universities would shut things down in the event of a major virus breakout. But the officials did not really offer clearcut answers, and basically just reiterated that the schools would be able to keep things under control.

For example, Valerie De La Rosa, chairperson of the C.B. 2 Reopening Working Group, asked them what infection percentage would lead to a campus lockdown.

The New School’s Malsin said they are “still working through these issues” but that the university would alert “partners and the community,” if needed.

“I think, for us, we are smaller and it would be easier to contain,” she said of an outbreak.

Ciotoli noted that N.Y.U. has the ability to do contact tracing, has “a direct line to the city” and also will be doing frequent testing of students, faculty and staff.

“The goal would be to test everyone with some regularity,” he said.

Ciotoli was asked about the word going around that many N.Y.U. professors reportedly oppose the idea of teaching in-person classes.

“I’ve not heard of a shortage of people to teach,” he said, though admitting that was not his area of focus.

Malsin added that New School students will be asked to adhere to a “statement or responsibility” and will also be required to attend a two-hour informational session on how to behave during the health crisis.

N.Y.U.’s Peralta noted that students could face being banned from certain buildings or the the entire campus for bad behavior.

However, the general question was posed as to whether 18-to-22-year-old students can realistically be expected to act responsibly, in terms of wearing face masks and social distancing.

Ciotoli, who has spent 20 years in student health, acknowledged the challenge, but said that penalties and “social norming” would be effective. The N.Y.U. and New School officials also said they will rely on community members to contact the universities with complaints, echoing the subway safety mantra, “If you see something, say something.”

The N.Y.U. doctor said it was encouraging that, “for the most part, people did the right thing” during the summer in New York City, and that he expected this behavior would continue since it is now “embedded” in the state and city.

In general, to enter N.Y.U. campus buildings, students will have to fill out a daily health screener and wear a face mask.

Malsin said New School students must wear face masks on campus.

De Rosa asked how N.Y.U. and the New School would handle students who leave campus for the weekend to travel outside the city.

“We will require notification of anyone who is traveling,” Malsin said. “If they’re going to a hot spot, they will have to quarantine for two weeks [upon their return].”

Ciotoli noted there will be a “daily screener” sent out to students. If a student visited a hot spot, he or she won’t be allowed into campus buildings until after quarantining and testing.

This Tuesday and Wednesday, for example, 2,700 N.Y.U. students arrived on campus from states that are currently on Governor Cuomo’s quarantine list. They are being required to quarantine for two weeks, so that they will be ready to attend the start of classes on Sept. 2. During their isolation, these students will be served meals three times a day by the university.

Also on the subject of food, Ciotoli said the N.Y.U. dining plan “will be phased in,” but that as of now, it will be “grab and go” to minimize contact between individuals. But it will only be a “limited plan,” he said.

New School students, meanwhile, will have to buy their own food because the university won’t be providing it.

C.B. 2 member Daniel Miller asked about a potential “doomsday” scenario, or, as he put it, “at what point is the opening a failure?”

Ciotoli responded that 5 percent of the university’s housing is being set aside for “isolation rooms” for sick individuals.

“It can be just a couple of weeks until you go from a couple of cases, to dozens of cases to hundreds of cases,” he acknowledged.

Ciotoli conceded it would be harder to monitor the compliance of off-campus students who are returning from hot spots, in terms of whether they properly quarantine for two weeks.

In general, it wasn’t clear how much of the students’ self-reporting on travel and the like would be based on an honor system, or if the universities would be doing any verification of this information.

Bob Ely asked how the schools are approaching the holidays, when many out-of-state students typically return home.

N.Y.U. is encouraging students who go home for Thanksgiving to “stay home,” Ciotoli said, since the university will try to do many of the final exams remotely.

Commenting in the chat sidebar of the Zoom meeting, local resident Rebecca Karl also pushed for concrete details on what would trigger a shutdown.

“What are some specifics?” she typed. “What is break point for shutting down? How many N.Y.U. folks need to get sick and/or die, and how many in the community need to get sick and/or die before N.Y.U. shuts down? Whose lives are being counted?”

C.B. 2 Chairperson Carter Booth raised a concern about crowding and less seating in Washington Square Park now that N.Y.U. students are returning to the Village.

“If they’re not allowed to congregate inside the dorms, they’ll go right outside and stand around and talk,” he predicted.

Ciotoli responded that N.Y.U. might “repurpose” its COVID-testing tent on W. Fourth St. for study space, and that the university would also partner with WeWork to obtain more space.

“Can I guarantee the park is not going to be crowded?…” he said, leaving the question hanging unanswered.

In general, the N.Y.U. health official said, N.Y.U. is estimating that 60 to 65 percent of its students — including off-campus students — will be around the campus. Even though they won’t all be attending classes, some will be using libraries and the like, he said.

Booth stressed that crowding in the park is an important issue for the community.

“It’s an impact that’s hard to address,” he said, “but for those of us who live here, it’s very real. It’s something I expect to hear about.”

Ciotoli said, as far as he knows, there is no plan to conduct N.Y.U. classes in the park — at least not formally, that is.

“So that shouldn’t be a concern,” he assured.

In addition, Booth, along with board members Michael Levine and Matthew Metzgar, stressed that local small businesses are suffering and that the students’ patronage is important for their survival. Metzgar suggested, for example, that students should really try to pick up their food themselves rather than ordering it through delivery-service apps, like Seamless or DoorDash, which skim a commission of up to 20 to 30 percent off the tab, hurting the small businesses’ bottom line.

Peralta said that’s definitely something N.Y.U. can stress to its students.

Be First to Comment