BY BILL WEINBERG | Over most of the years I’ve lived on the Lower East Side, the story of the blocks of vacant lots on the south side of Delancey St. east of Essex was a bit of an open secret. It was well known that public housing slated for those sites way back in the ’60s was being held up due to the influence of Sheldon Silver — less in his official capacity as state assemblymember (and later Assembly speaker) than his unofficial one as political boss of the Jewish community based in the blocks immediately to the south.

The ugly racial politics behind the state of affairs were palpable: The empty blocks were being maintained as a buffer zone separating this enclave from the Puerto Rican and Dominican residents north of Delancey. And many Puerto Ricans had been displaced when the housing on those blocks was razed long ago.

Now that there is finally progress in developing those lots, a book has been released on this contentious saga. “Contested City: Art and Public History as Mediation at New York’s Seward Park Urban Renewal Area,” by Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani (University of Iowa Press, 2018), emerged from coursework the author developed on the issue as a New School professor. She was also inspired by her family roots in the neighborhood two generations back — in fact, in the co-op housing complexes south of the contested blocks that would later become Shelly Silver’s stronghold.

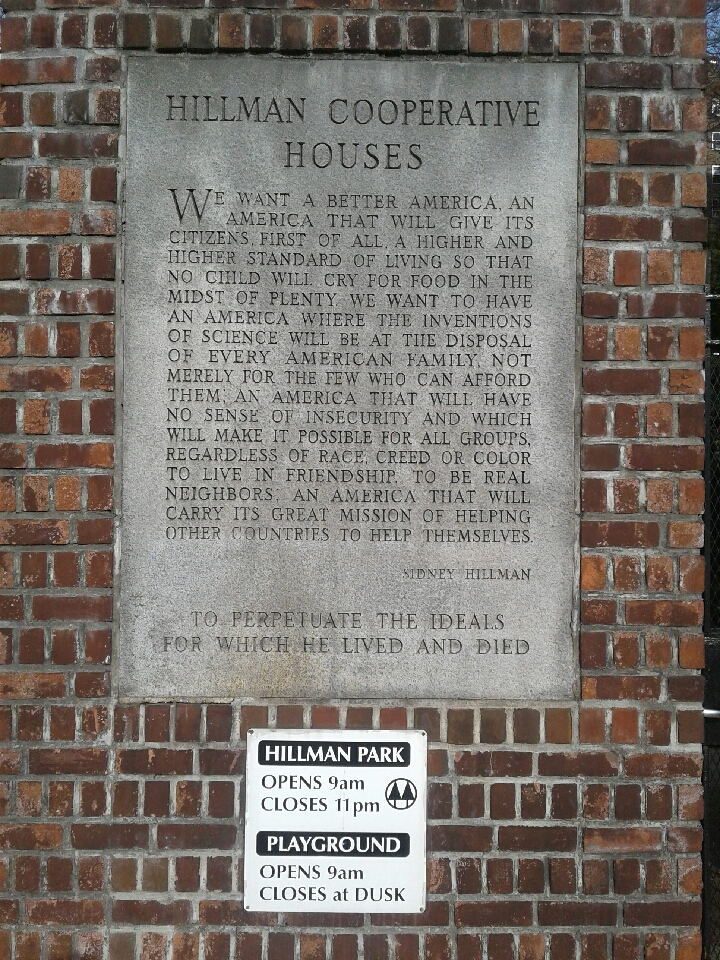

These co-ops were not the luxury affairs of the gentrification era. On the contrary, they were developed by trade unions (initially the Amalgamated Clothing Workers) for members and their families in the New Deal era. The real tragedy of this story is that it is one that pitted the working class against the working class — or, one group just on the cusp of middle-class security against those living at the level the first group’s own parents or grandparents had.

The blocks in question, targeted by a “slum clearance” plan as a “substandard or insanitary area,” were razed in 1967. The sites were turned over to the city’s Housing Authority for the development of new projects. Some 1,700 families — overwhelmingly poor or working-class, and mostly Puerto Rican — were displaced as the buildings came down. They were promised (eventual) apartments in the new developments by the too-aptly named city Department of Relocation.

But as the project moved ahead, under the rubric of the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area, or SPURA, the plans changed. The displaced tenants had to fight — first, in the courts — to get the city to honor its commitment to them.

The case in question was Otero v New York City Housing Authority, argued under the Fair Housing Act 1968 (Title VIII of that year’s Civil Rights Act), which barred discrimination in federally funded housing. In 1972, U.S. Judge Marvin Frankel allowed the class-action suit to proceed, noting that the project had “fueled fires of racial competition.”

The Housing Authority employed in its defense the Orwellian argument of the “tipping point” — the point at which white residents will flee a neighborhood in response to a demographic tilt to the black and brown. The specter of white flight was raised to argue that letting all the sites’ original residents return would have a negative impact “on the racial balance in the project.” A decision in favor of the displaced could “violate the Authority’s duty to prevent segregation in public housing.”

Bendiner-Viani rightly calls the “tipping point” notion an “index of white racism,” and emphasizes the irony that the Housing Authority was using its mandate to “maintain integration” as a cover for maintaining a white majority.

This argument was rejected in a 1973 ruling by Judge Morris Lasker. But his decision was reversed later that year by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which found that the Housing Authority could “limit the number of apartments to be made available to persons of white or non-white races…to avoid concentrated racial pockets.”

Before the case could proceed to the Supreme Court, Judge Lasker presided over a settlement in 1974, finally seeming to end what The New York Times called a “bitter, ethnic dispute.” Under terms of the settlement, the ethnic ratio in the new projects would be about the same as it had been in the destroyed tenements — that is, 60% “Hispanic and non-white” and 40% “white” (taken to include Jewish, of course).

‘This was the start of the long stalemate, in which every bureaucratic artifice available under the Unified Land Use Review Process (ULURP) was used to gum up any move toward starting construction on the sites — at least any move under terms of the settlement. Silver consolidated his machine, in large part, around the issue. The language used was very blatant. Silver’s chief lieutenant, William Rapfogel of the Lower East Side United Jewish Council, or UJC, pledged in the group’s newsletter to “retain the distinctly Jewish religious and cultural identity of our community.”

Far more egregious were comments by Harold “Heshy” Jacob, manager of the Hillman Co-ops and UJC board member, who compared the ex-residents demanding their right of return to Palestinian “terrorists.”

Here’s where Bendiner-Viani reveals herself as somewhat out of her depth. She deserves enormous credit for bringing this indiscretion to light — but she badly garbles the analogy. In her imprecise paraphrase, Jacob had invoked Palestinians demanding their “right to return to Gaza and the West Bank” after the war of 1967, and she notes that this was the same year the tenements were razed. But the Palestinians were not driven from Gaza and the West Bank — they were driven into these territories, and in 1948 not 1967. The “right of return” being demanded by Palestinians is to former homes within Israel proper.

It would have been better if Bendiner-Viani had provided Jacob’s verbatim quote, which was from a 2010 interview with The Lo-Down Web site (and was less confused if no less ugly).

Jews are not all demons in this story. One of Bendiner-Viani’s key sources is Tito Delgado, a leader of the displaced tenants. He enthuses that the professional housing advocates who came forward to help their fight (from groups like Metropolitan Council on Housing and the Lower East Side Joint Planning Council) were “mostly Jewish women!”

It was the group Good Old Lower East Side (GOLES) that initiated the 2009 study “SPURA Matters,” which took testimony from neighborhood residents and called for mixed-income housing to be built on the sites. The long logjam finally broke just a few years before Silver and Rapfogel were both convicted on corruption charges, ending their reign and sending them to prison (although Silver is currently free while his case is on appeal).

The turning point came in 2011, when the city approved mixed-income housing for the sites, to include some 1,000 “permanently affordable” apartments. But Bendiner-Viani calls out the bureaucratic subterfuge employed to tilt the scales of what is “affordable” to the high end of the spectrum. This category is based on the median income of the New York “metropolitan statistical area” defined by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development — which actually includes the upscale suburbs of Westchester, Rockland and Putnam counties. This, of course, “artificially raises the median income” used to determine “affordability” on the Lower East Side.

A proposal for 100 percent low-income housing on the sites, pushed by groups including the Chinese Staff & Workers’ Association, was defeated.

Since then there has been some progress, including the recently completed Essex Crossing complex, built by a private consortium at the corner of Delancey and Essex Sts., and the senior housing facility named for longtime neighborhood advocate Frances Goldin, at 175 Delancey. In all the intervening years, only two buildings had gone up on the sites — the Seward Park Extension bloc, run by the Housing Authority.

As a first shot at telling this history, “Contested City” leaves room for other writers to follow up. Frustratingly, some really vital stories that emerge are not fleshed out with nearly enough detail. For instance, Tito Delgado is quoted telling how he and other displaced ex-residents began squatting one of the condemned buildings that hadn’t yet been torn down, at 36 Attorney St., and eventually got it legalized as a co-op under the city’s homesteading program, saving it from the wrecking ball. But we aren’t told what year they began squatting it, what year it was saved, or exactly how its original address was changed to 157 Broome St. as the Seward Park Extension and other projects were built around it.

The bigger problem with this book is Bendiner-Viani’s self-consciously self-referential treatment. The history is regularly interrupted with accounts of how it is interpreted by her students in their artistic projects and tours of the neighborhood, and descriptions of what she ostentatiously calls “my pedagogical practice.”

To throw around some postmodern jargon of my own, the history is being viewed through the exotifying gaze of privileged academics.

The Lower East Side might have been better served by a more traditional, and rigorous, rendering of the history. And one in which the neighborhood’s residents were more subjects and less objects.

Weinberg is editor of CounterVortex.org.

Excellent!