BY GARY SHAPIRO | Dr. Dwight A. McBride, who joined The New School this April as its ninth president, offers a metaphor to describe the university he now leads.

“Social justice is baked into the DNA of The New School.”

The New School’s early years earned it the famous appellation “the University in Exile,” after taking in many prominent refugee scholars fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe.

McBride was recently mindful of that legacy, when he participated in a coalition of educators who opposed an Immigration and Customs Enforcement proposal that would have kept international students from coming or staying here if their programs of study were solely online. McBride told The Village Sun that the failed ICE proposal was “mean-spirited.”

What are some of his goals as president? McBride wants to broaden the sense of belonging and sense of home in The New School community. He also wants to build stronger alumni participation.

“We want to be among the most important institutions in their lives, not just while they are here but also afterward in their professional lives,” he said.

One goal involves making sure The New School remains part of important conversations in New York, the nation and in higher education, generally. The university’s desirable location in the heart of New York leads McBride to refer to it as its “geographic endowment.”

McBride is an experienced and gifted administrator.

Prior to his appointment at The New School, McBride was provost (chief academic officer) and executive vice president for academic affairs at Emory University, where he also held the position of Asa Griggs Candler Professor of African American Studies, Distinguished Affiliated Professor of English and Associated Faculty in Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies.

Prior to Emory, he was at Northwestern University, where he was dean of the graduate school and associate provost for graduate education, as well as the Daniel Hale Williams Professor of African American Studies, English and Performance Studies.

He was also formerly dean of the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he had also been chairperson of the African American Studies Department.

One of his accomplishments at Northwestern was significantly increasing the number of Ph.D. students coming from underrepresented communities. At University of Illinois at Chicago, he helped found an Institute for Sustainability, which delves into climate issues.

McBride’s talents as an administrator are matched by his achievements as a scholar.

He co-founded a journal devoted to James Baldwin, the black writer, playwright, essayist, activist and intellectual.

“Baldwin distilled the problem of race in America,” McBride said, noting that Baldwin’s voice continues to resonate powerfully in the present. McBride said there has been renewed interest in Baldwin, with manifestations such as one-person shows, books and film.

“It’s an incredibly committed and broad group of scholars from all over the world who are drawn to Baldwin’s work,” he said.

McBride’s distinguished books include “Impossible Witnesses: Truth, Abolitionism, and Slave Testimony” (NYU Press). He also co-edited a black gay and lesbian literary fiction anthology called “Black Like Us” that won a “Lammy,” as Lambda Literary Awards are known.

He was also awarded the Monette/Horowitz Trust 2003 Achievement Award, which was for independent research combating homophobia. There was no application for this prize: A check just arrived mailed in an envelope.

“It spurred me on and encouraged me,” he said

His research has been supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, among other prestigious funders.

McBride is an editor with Darlene Clark Hine on The New Black Studies book series at the University of Illinois Press that pushes the boundaries of the field.

“Black Studies has had silences,” McBride noted.

The wide-ranging series has published about 40 books so far on topics ranging from the rise and fall of Chicago’s first black-owned theater to Booker T. Washington.

“It’s been a labor of love,” McBride said.

He has co-edited the posthumous books of two colleagues: Lindon Barrett’s “Racial Blackness and the Discontinuity of Western Modernity” (University of Illinois Press) and Vincent Woodard’s “The Delectable Negro: Human Consumption and Homoeroticism within U.S. Slave Culture” (NYU Press). Woodard died in his late 30s and Barrett in his mid-40s.

McBride grew up in a working-class family in rural South Carolina in a town called Belton.

“It was a friendly town where people looked out for each other,” he recalled.

“I’ve had the good fortune that people took an interest in helping and encouraging me,” he said. “I didn’t grow up in a context where the wealth of options of the world were immediately apparent.”

He found mentors early on, such as a neighbor, Carolyn Pratt, who was a friend of his mother and a teacher. Pratt offered an example of what it would mean to be a black professional. She also encouraged the McBride family to have him pursue an honors curricular track.

“No one accomplishes things solely on your own,” said McBride, who is a first generation college student.

He also had a high school English teacher named Sue Tomlinson who “really deepened my love of literature,” he recalled. She was his adviser when McBride became State Student Council president and held its convention in his hometown.

Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison was a “deeply formative” mentor to him. He was a research assistant of hers for a year and a half at Princeton.

“We stayed connected,” he said. “She was an important interlocutor at important moments in my career.”

Other mentors have included Ruth Simmons, former president of Brown University, who the first black president of an Ivy League school.

Yet another mentor is Valerie Smith, a scholar of African American literature who is the 15th president of Swarthmore College. McBride was a student of Smith’s at Princeton and again at U.C.L.A., where she was on his dissertation committee.

“We have a peer-mentoring relationship today,” he noted, adding, “Mentors should be part of every stage of our lives.”

Another influence was Albert J. Raboteau, a religion professor at Princeton for whom McBride served as undergraduate teaching assistant.

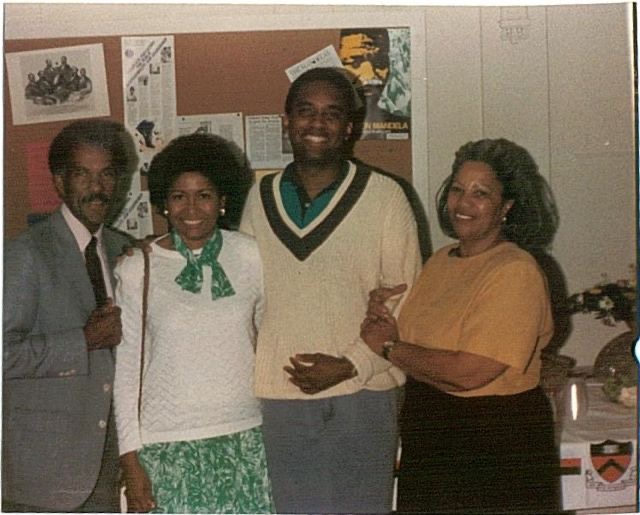

His senior thesis at Princeton was on poet and slave Phyllis Wheatley, a subject to which he is returning. It won the African American thesis prize at Princeton, which was given to him by Cornel West, who was then director of the African American Studies program. McBride described how his parents love to reflect on meeting Cornel West at Princeton graduation.

In New York, McBride loves the theater, galleries, museums and restaurants and is looking forward to their reopening. The New School, which was founded in 1919, recently celebrated its centennial.

“We’ve been here for a century and we’re going to be here another 100 years and longer,” he said.

McBride succeeds the law professor David E. Van Zandt as president of The New School, after Van Zandt served in that position for nearly a decade.

McBride made a personal lead pledge of $100,000 to The New School’s Student Emergency Assistance Program, which provides short-term support to students with urgent needs, focusing on those caused by COVID-19. The New School’s classes will be online this fall due to COVID-19.

McBride treasures a number of quotes, one of which is by the African American human rights and civil rights activist Ella Baker, who said, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.”

Be First to Comment