BY ART GATTI | Twenty years after D-Day. Americans old and young, Black and white, mounted a second assault on the forces of repression — but this time against those within our borders, in what has become known as Freedom Summer.

Throughout most of our southland, Black people were being denied their places in our society…poor schooling, or no schools at all, forced forms of abject poverty, the denial of the right to vote, and savage repression against any who might challenge the status quo, and what were called Jim Crow Laws. Beatings and lynchings were all too common, often under the noses, and more often with the O.K. of, so-called law enforcement.

Among the victims of these crimes were men and women who had given every effort it took to win the world war that ended two long decades earlier. Veterans who were Black were told, when they returned home, “Nothing has changed, [N-word], so mind your place!”

But, finally, these racist crimes no long went unnoticed, as they had for so many scores of years. Unlike the brief radio broadcasts their parents had heard when their families were fighting the fascist war machine, young Americans were being inundated with TV news — news depicting these ongoing and intolerable injustices.

Activists, students and volunteers of every age, color and creed joined with groups like CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) and Dr. Martin Luther King’s group, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), that put out a call to campuses and cities all over the land: “Come join us!” they urged, “We have America’s work to do.”

My school, Queens College, had been in the thick of the fight ever since school integration became law. And when I first arrived, I could not help but join CORE and SNCC and all the rest. So when the summer of ’64 arrived, I was determined to help make a difference, along with thousands of my fellow citizens.

But there was a problem… .

In 1963 I was a member of the Queens College Mexico Volunteers. Among those in the group was Mario Savio, the future “non-leader” of the U.C. Berkeley Free Speech Movement of 1964-65. We were friends who had grown up and gone to public schools together. And while we both made our way to Mexico, only I would return to Queens at summer’s end. Savio, who we knew as Bob in those days, would join his family in California, where they moved late in the season.

Before leaving Mexico, however, Savio had arranged with an old veteran of the Revolution — a man who had ridden with Zapata —to come back the following summer to build a school in a desperately poor mountainside slum in the state of Guerrero. Savio needed me to provide most of the volunteer manpower from Queens, while he promised to do all he could from the West Coast.

But when the Freedom Summer fervor caught hold at Berkeley, he told me that Mississippi would be his summer of ’64, and that the school project was in my hands alone.

Yes, I loved my poor Mexican town, but it was in Freedom Summer where I most wanted to be involved. So I accepted my fate, my obligation, and went about the springtime campus on Long Island trying to recruit young men to accompany me in Mexico.

With my co-organizer, Kevin Donnellan, we traveled the campus to recruit volunteers. By the end of the school year we were five, the others having been Jeffrey Feinstein, Charles Emonds and Joseph Belvedere. But we were still shorthanded and needed to expand our ranks.

Kevin and I were zeroing in on a serious young man who told us that he wanted to spend a summer doing something worthwhile. We hoped he would see that bringing education to an impoverished land would qualify. But, as I noted, the fervor for Freedom Summer was everywhere.

An then I made a bad decision, inviting that young student to our first reuniting of the past year’s volunteers… .

They were happy to see each other again, upbeat about their various accomplishments improving the lot of Mexico’s poor. They spent most of the reunion exchanging photographs and remembering joyous times.

The young man, Andrew Goodman, told Kevin and me, “I need to do something more committed — I need to join Freedom Summer.”

I put one hand on his shoulder, shook his hand with my other, telling him, “I respect that more than you know. In fact, if I could get out of organizing to go to Mexico this year, I would be joining you” — of course, never imagining… .

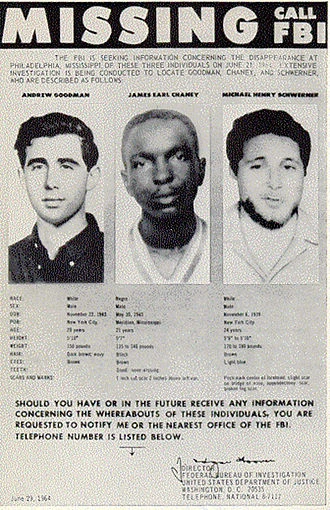

It was during August of ’64 that we heard that Andy and two others had gone missing, and we knew what that meant.

The school project was successful, changing the economy of the mountain slum it served in so many ways. Ten years later Apple adopted La Escuela Emperador Cuauhtemoc, donating a Quonset hut full of some of the world’s first school computers.

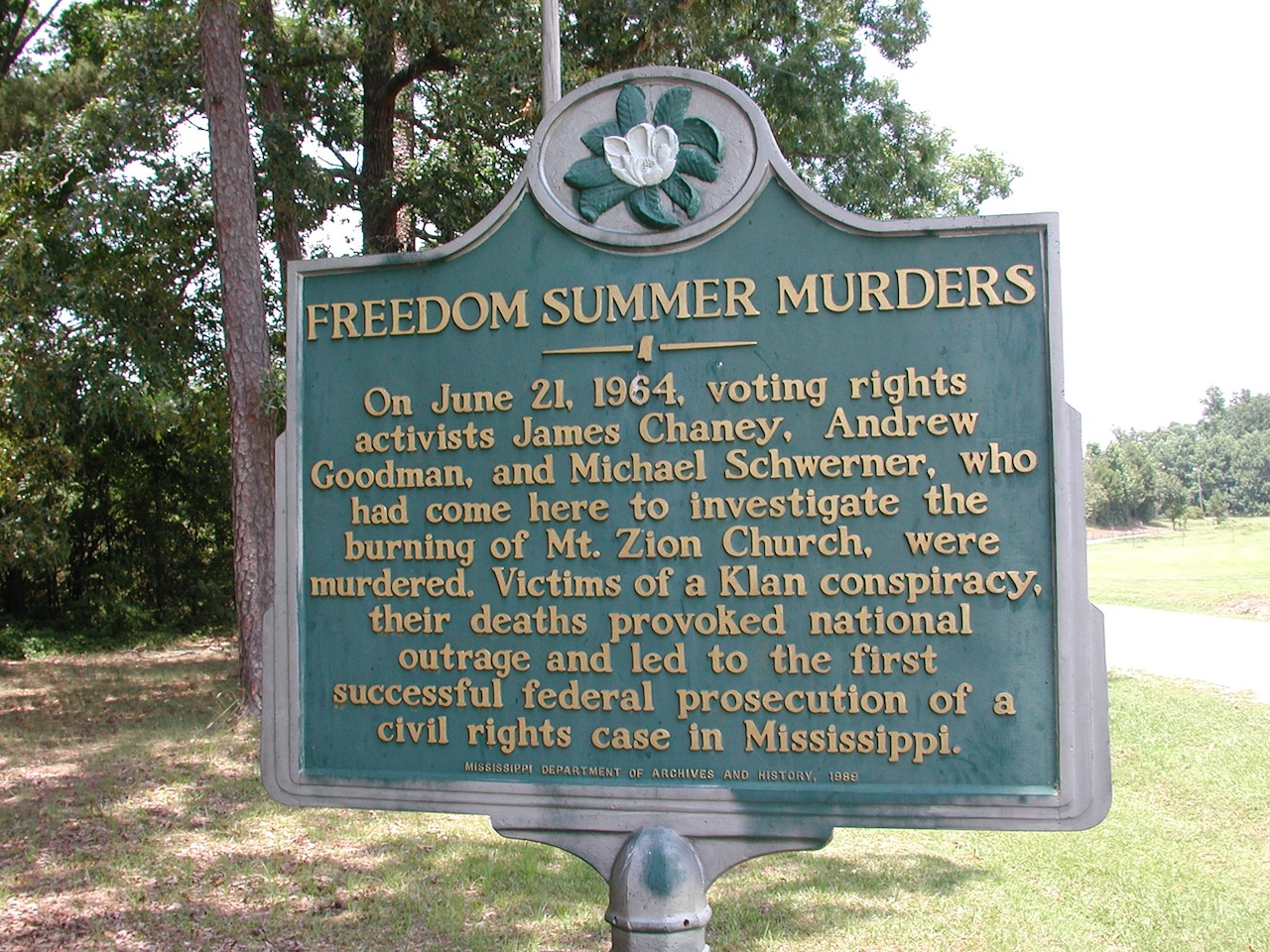

And in the U.S.A., the Voting Rights Act was passed after the martyrdoms of James Chaney, Mickey Schwerner and Andrew Goodman. But as Phil Ochs said — “Too many martyrs!”

Wow! What a story! I’m so glad for the success of the school in Mexico. And I’m so sorry for the three civil rights workers who were killed. One of them was a grade-school friend of Robert Reich, who sometimes mentions him gratefully — as he defended the diminutive Robert from bullies.