BY GARY SHAPIRO | This year marks the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote. Greenwich Village played a role in the long journey of women’s suffrage that led to ratification on Aug. 18, 1920.

Humanities New York has an intriguing new podcast called “Amended” that is hosted by Laura Free, a professor at Hobart and William Smith colleges.

The podcast puts suffrage in a wider context and reveals the complexity of the path to women’s rights. Scarlett Rebman, the director of grants at Humanities New York, said that the podcast’s goal is to share stories of people who fought for voting rights not based on sex alone. The women featured on the podcast address oppression based on race, class and citizenship status.

“Sex was never the only battleground for equal voting rights,” said Free, who is a historian of women and politics. She is author of “Suffrage Reconstructed: Gender, Race, and Voting Rights in the Civil War Era” (Cornell University Press).

A number of people and institutions in the Village played a role in helping women win the right to vote.

Max Eastman, a Columbia University doctoral student, helped found the Men’s League for Women Suffrage in 1909. The organization’s first office address was listed as his home, at 118 Waverly Place near Washington Square. He later moved to 6 E. Eighth St. in 1917, and to 11 St. Luke’s Place in 1920. His older sister Krystal Eastman was also a prominent suffrage activist.

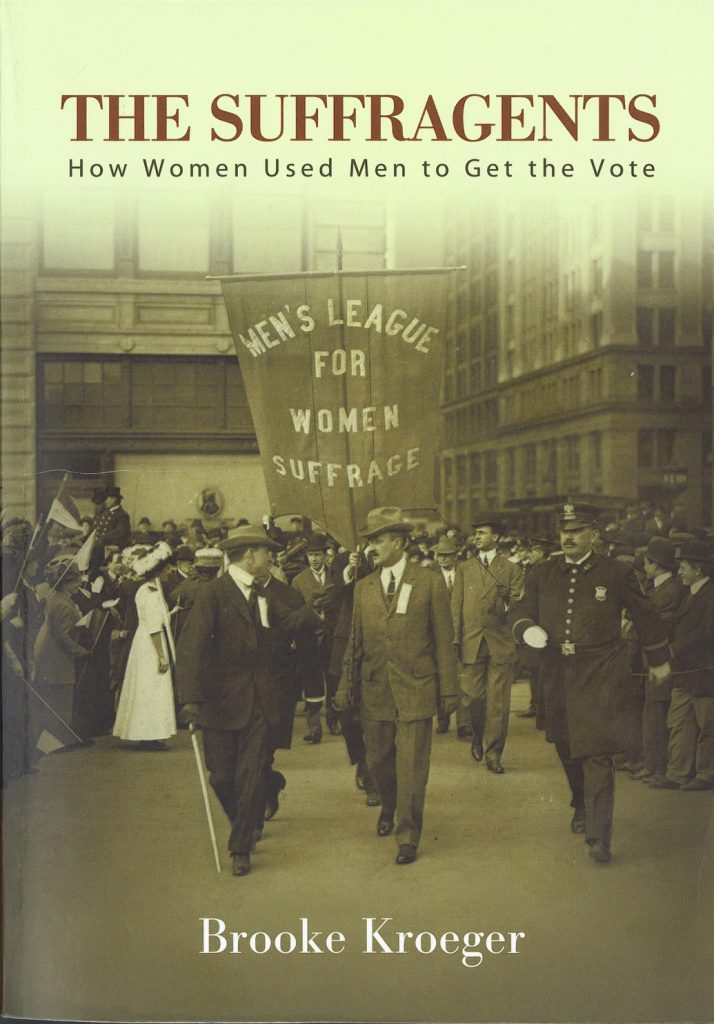

Brooke Kroeger, a professor of journalism at New York University, in her book “The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote” (Excelsior Editions/State University of New York Press) wrote, “The founders of the Men’s League knew that to help sway the course of history, they needed a full-fledged national, then multinational organization, with all the effort and expense that implied.”

Eastman was asked in 1912 by the Democratic presidential hopeful Woodrow Wilson to brief him on the suffrage question. As the anecdote goes, this resulted in their conversing on the subject for several hours.

“I like to think I did some important teaching during those hours,” Eastman later reflected.

Union Square has long been a focal point for parades and marches urging change in society.

There was also heightened labor activism in the wake of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Greenwich Village in March 1911. This was the massive industrial tragedy in which locked exits caused 146 workers, mostly women, to be killed.

Clara Lemlich, who lived at 278 E. Third St., led the New York Shirtwaist Strike in 1909.

The Cooper Union hosted a number of suffrage events at its Great Hall, on E. Seventh St., over several decades, including the 1860 National Woman’s Rights Convention, the 1873 meeting of the American Woman Suffrage Association and an 1894 suffrage gathering attended by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and other leaders.

The Cooper Union also witnessed the presence of prominent speakers from across the Atlantic. British suffragist Anne Cobden-Sanderson’s American tour in 1907 drew thousands of people to Cooper Union to hear her speak. She disparaged the comparatively slow pace of the American suffrage movement’s progress. Another famed British suffragist, Emmeline Pankhurst, likewise appeared at Cooper Union in 1909, speaking to a welcoming audience of her own.

Free, the “Amended” podcast host, explained, “One of the key ideas that Americans carry with us about the movement for women’s voting rights is that it started in 1848 with the Seneca Falls Convention, and ended in 1920 with the 19th Amendment. And while these are certainly key touchstone points in the fight for women’s equal access to the ballot, there really aren’t such clearcut starting and ending points as this.”

She said, for example, that women with property voted in colonial Massachusetts and in the state of New Jersey until 1807.

The upcoming fourth episode of “Amended” will have two parts about the suffrage activism of immigrant and working-class women. Rebman, of Humanities New York, said that the first part of the episode highlights the life of Rose Schneiderman, a Polish-born woman who worked to build political power through union organizing and voting rights.

Schneiderman and her family members resided at 57-59 Second Ave. in 1905. A leading figure in the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, Schneiderman spoke in 1907 at The Cooper Union with Harriot Stanton Blatch (Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter) and Rose Perkins Gilman on women’s suffrage.

The second part of the upcoming episode features Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1896-1966), who was born in China and became politically engaged as a teenager while attending high school here in New York. In 1912, Lee helped to lead Chinese-American marchers in a large suffrage parade that began in Greenwich Village. She was a suffragist whose feminism was grounded in Chinese culture.

Inez Milholland, who lived at 9 E. Ninth St., earned a law degree from New York University, and became an activist for pacifism, prison reform and workers’ rights, in addition to suffrage. At the National American Woman Suffrage Association Procession in 1913, she appeared out in front on a horse as a present-day Joan of Arc in a blue cape and golden tiara.

During this year, 2020, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation put together a stellar interactive 19th Amendment Centennial StoryMap of Greenwich Village, which is considerably more comprehensive than this article. It shows, among other things, how three famous abolitionists, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, all prayed in the Village at Mother Zion AME Church, which was at 215 W. 10th St.

Sarah Smith Garnet, who lived at 175 MacDougal St., created the Equal Suffrage League, an organization for black women. She was also the first female black school principal in the city.

Martha S. Jones, a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, who is a guest on the “Amended” podcast, said, “There have always been Black suffragists as long as there have been suffragists.” She is author of “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All” (Basic Books).

Jones told The Village Sun that African-American women have been part of the debates over women’s rights, including the vote, since the 1820s.

“Their work emanated out of antislavery societies and Black churches rather than women’s conventions, in the early years, and later through organizations like the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs,” she said. “Anti-Black racism kept most Black women away from suffrage associations, but still they were committed activists in the struggle for women’s votes.”

Jones told The Village Sun that Black women played a unique role in the movement for women’s votes, in that they insisted that the movement aim to defeat both racism and sexism in American politics.

“Too many Black women did not win the vote in 1920 with ratification of the 19th Amendment,” she said. “They remained disenfranchised by state laws — poll taxes, literacy tests and more — along with intimidation and violence, especially in the American South.”

“We know that Black activist Maria Stewart called for women’s political rights in the 1830s,” noted Free, the “Amended” host, “and that Upstate New York women petitioned the state Legislature for the ballot in 1846 — all well before the Seneca Falls Convention.”

Free said the statement that the 19th Amendment enfranchised “all women” just does not align with the historical evidence.

“Indigenous women were denied the right to citizenship until 1924, so were not enfranchised by the 19th Amendment,” Free added. “And even after that, they faced similar legal restrictions to their voting rights in western states, as did Black Women in the South. Likewise, Chinese and Japanese immigrants and their children were denied citizenship and the ballot until the 1940s and 1950s.”

Free said that legally imposed racist restrictions on women’s right to vote were not remedied until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The podcast “Amended” has contemporary relevance. Rebman, of Humanities New York, said, “Through carefully crafted storytelling, “Amended” creates a sense of intimacy with this history and inspires listeners to honor and carry on the legacy of suffragists today.”

Be First to Comment