BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Judy Richheimer, the immediate past president of the Chelsea Reform Democratic Club, died on Fri., March 27, a victim of coronavirus. She was 70.

Richheimer, who lived in London Terrace — across from The Rail Line Diner — was C.R.D.C. president from January 2019 to January 2020. She chose not to run for re-election.

According to Brian Mangan, who was the club’s executive vice president during her tenure, she entered Lenox Hill Hospital on Monday and died Friday morning.

District Leader Steven Skyles-Mulligan, a former longtime C.R.D.C. president, said Richheimer did have a couple of underlying health conditions, including high blood pressure.

It was not clear where Richheimer contracted the virus, but she was renowned for attending tons of events — from politics to arts and culture — and being very social.

“I talked to her a couple of weeks ago,” Mangan said, “and I was nervous about her because she goes to so many events. She said, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah… .’ She was one of the first people I would worry about in this situation because of her age and because she was very active.”

Jeffrey Gold, the board chairperson of Metro New York Healthcare for All Campaign, became good friends with Richheimer in recent years, bonding with her over a shared interest in politics and cultural events.

“She called me from the hospital when she was rushed up Monday to tell me she was hustled out without her cell phone and personal effects,” he said. “I was going to bring her a radio so she could listen to NPR. I was going to give her my iPad, I was going to sterilize it.”

But hospital staff wouldn’t let him bring her things to her bedside due to the highly contagious pandemic.

“Her voice sounded bad,” he recalled. “I said, ‘You have a raspy voice.’ I asked her if she had been tested. She said, ‘I think I have it.’”

Richheimer praised the EMS medics who had rushed her to the hospital, which was “typical for Judy,” Gold noted.

During the phone call, she also talked at length with Gold about the Skyscraper Museum’s exhibit “Housing Density: From Tenements to Towers.” She had just seen the exhibit several days before.

“There was a model of London Terrace in the exhibit,” he said. “We were talking about that and about how density now is a factor in [coronavirus] transmission.”

After that talk, he was able to reach her once more, when he called her the next day.

“She sounded weaker and more fatigued,” he said.

Gold said Richheimer had gone out for dinner with a friend to a local Chinese restaurant on the last night that New York City restaurants were allowed to be open, two weeks ago, and was starting to show signs of sickness.

“She didn’t look well, she began to look gray,” he said.

Judy Richheimer was born on July 30, 1949. She grew up in Flushing, Queens, a doctor’s daughter.

She attended New York University and was involved in theater in her younger years.

Earlier in her career she was a journalist, writing for the likes of Vogue, Details, Hollywood Reporter, Publishers Weekly and New York magazine. In more recent years, she contributed articles to Chelsea Now, writing on transit issues like handicapped access and the 23rd St. Select Bus Service.

Adding a second career, she was also a tour guide, becoming a leading member of the Guides Association of New York City.

In C.R.D.C., she was known as a staunch advocate for reform Democratic politics — and a stickler for reform procedures — with a particular interest in judicial races. She had been a club member for about 15 years, according to Mangan.

Mangan said Richheimer really went the extra mile in all she did when she was president and as a club member, in general.

“A lot of people just get elected to a position but they don’t know what the job entails,” he said. “She would pick up the slack when other people wouldn’t do the work.”

That even entailed arriving an hour early to the monthly meeting to bring refreshments — cheese and soda — if needed.

Her real passion was organizing the events for the club’s general meetings.

“She would pick a theme, like commercial rents or NYCHA, immigration, the importance of the census or particular bills,” he recalled. “Getting the panels of speakers together, it’s a lot of work.”

As for her politics, Mangan said, “She was a reformer at heart and a really tenacious fighter for small ‘d’ democracy — and that certainly did not endear her to some.

“She had a huge heart and was willing to take on forces that were less democratic than we would like.

“One of the things that she cared about very deeply was [Assemblymember] Dick Gottfried’s single-payer healthcare bill. … She had an apartment. She cared about people that didn’t have enough.”

She was deeply concerned about electing progressive judges to the bench. For the last 15 years, she was an elected judicial delegate.

She had her own rigorous screening process for jurists running for re-election.

“She used to go to judges’ courtrooms and watch them, see them at trial,” Mangan said. “It’s something I’ve never heard of anyone else doing.”

Richheimer also simply enjoyed the thrill of being the club’s president.

“She had such a good time doing it,” Mangan said, “getting up on a chair to call out the name of a congressmember or politician to come up and speak.”

District Leader Skyles-Mulligan, who was C.R.D.C. president for two five-year stints, said Richheimer was endlessly curious.

“I think what made her stand out was she was inquisitive,” he said. “She was just utterly fascinated about how things worked, possibilities — about what would happen if.”

It was his call to put her in charge of the club’s programming, a job she went on to hold for 10 years.

Richheimer’s adherence to principles could sometimes rub more pragmatic club members the wrong way.

“She was always a stickler for her way — of the reform way — of doing it,” Skyles-Mulligan recalled. “And sometimes, frankly, it was a little aggravating. But these were arguments that she cheerfully and enthusiastically would have with whoever she had to have them with.

“She saw herself as the guardian angel of the reform tradition. She was always on guard and aware of getting into a lively debate.

“She was a real extrovert,” he added. “She was famous for her smile. She liked music, art and literature quite a lot. She went to anything…cultural, political. She went all over the city, to other [political] clubs, to events that elected officials were having.”

Skyles-Mulligan recalled an anecdote — about a news article she was writing — that captured Richheimer’s focus on integrity.

“She was asked to cover something related to the court system,” he said. “She said, ‘How can I write this thing if I’m going to be a judicial delegate?’ This is the kind of thing that kept her up at night.”

Added Gold, “I always told her, ‘You should have been a judge — you and Fran Lebowitz.’”

Richheimer’s friends recalled how she liked to send out e-mails about grammar and language — she was a devotee of what one called “old-school” correct usage.

“She was a flea-market fashionista who was always very well dressed,” Gold recalled. “She was always the person who would ask the first question at political events. She was very social, she liked to party, she liked guys.”

Gold, who did “door knocking” — voter outreach — with Richheimer in swing districts in the Hudson Valley, said she was perfect for it because she instantly put people at ease.

“She was friendly, well-spoken, not intimidating — and short,” he recalled. “I said, ‘You have all the qualifications we need.’

“She was on a budget,” he said. “She had a rent-regulated tiny studio apartment. She really needed the tenant protection.”

Gold dubbed her a “professional urbanist.” He recalled how she had favorite spots in the various boroughs, like the Jackson Diner, in Jackson Heights, Queens — which she loved for its Indian food.

“She was one of those people who make me want to be here,” he said. “She pushed back against people in power that are trying to make many of our lives — by omission or commission — worse. She’s a net positive for the city. She’s a New York character.”

Although Richheimer broke an ankle in February 2019 in a fall on the ice, limiting her mobility, she continued to attend important political events, even if they required significant travel.

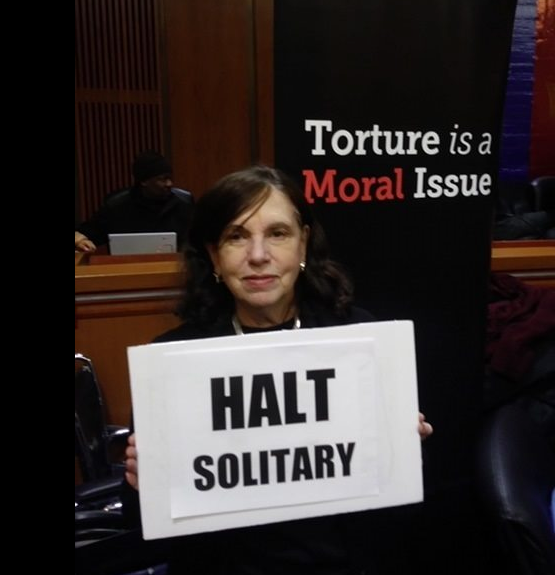

This past January — still on a crutch due to her injury — she rode the bus to Albany to join a protest against prison solitary confinement.

“A lot of people are all talk,” Mangan said. She did it. She couldn’t be stopped. And not doing it for Instagram.

“She was already looking forward to getting on the bus this summer and fall to swing districts to help defeat Donald Trump.”

Richheimer is survived by a brother who lives out of state and a niece and nephew.

She never married, but she had a longtime boyfriend whom she nursed before he died a few years ago.

“Judy was married to making the world a better place,” Mangan said.

According to Gold, 50 years ago Richheimer dated Michael Sorkin, the acclaimed architect and Village Voice writer.

Sorkin, 71 — who lived in the Village and had his studio in Tribeca — also was felled by coronavirus. He died Thurs., March 26, one day before Richheimer.

Skyles-Mulligan said Richheimer’s family planned to have her remains cremated and that there would be a memorial “once it’s O.K.”

“Maybe there will be a memorial on Zoom,” Gold added.

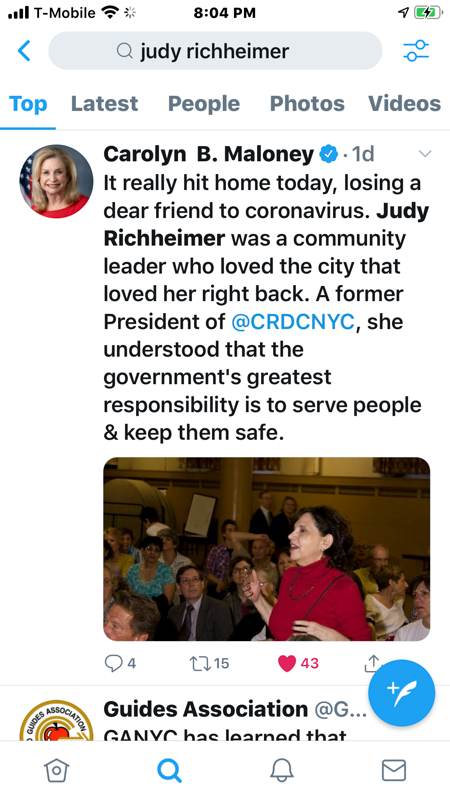

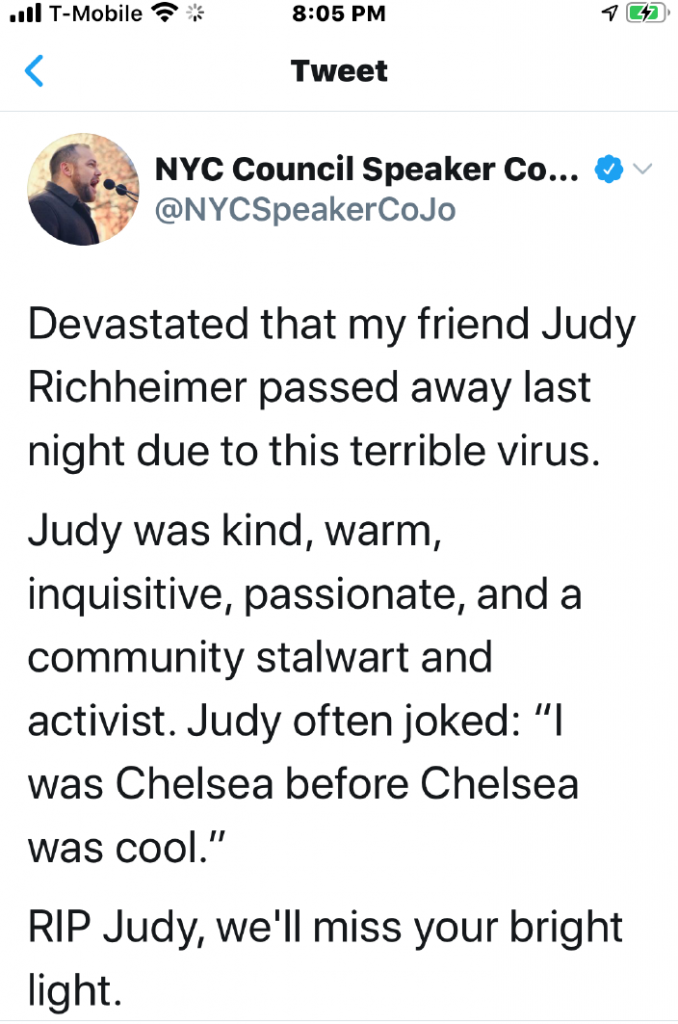

Local politicians tweeted their sadness at the passing of the community leader.

My darling friend, light of the morning. Goodbye, Judy Dear.