BY DASHIELL ALLEN | The smell of beef and blood is long gone from a corner of the former Meat Market district, but something doesn’t smell right.

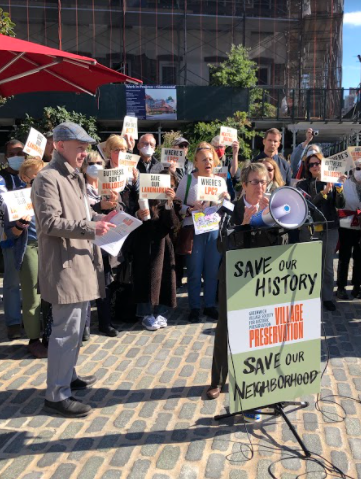

“Something is very, very wrong here,” said Andrew Berman, the executive director of Village Preservation, about the ongoing demolition of nine 1840s landmarked buildings in the Meatpacking District.

On Thursday afternoon Village Preservation joined neighborhood activists and local politicians to condemn the city’s actions and call for an immediate halt of demolition — demanding the city take action either to brace or repair the historic structures.

“Save these buildings!” “Save these landmarks!” the crowd chanted.

Ironically, their voices were occasionally drowned out by the familiar buzz of nearby construction sites on the sunny October day.

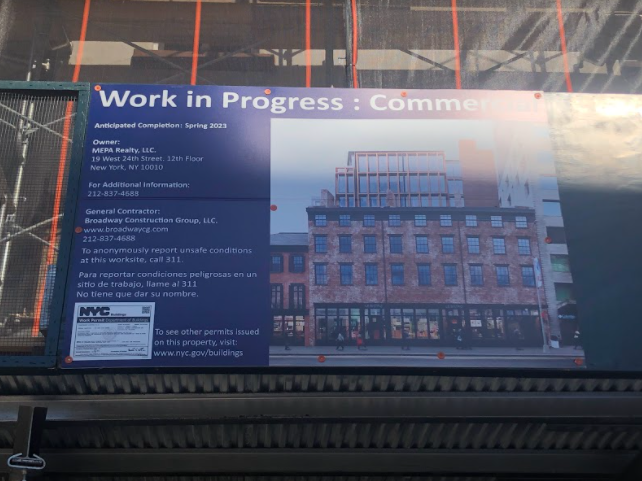

The buildings in question, at the northeast corner of 14th Street and Ninth Avenue, were acquired by the development firm Tavros Capital in 2020. The plan was originally to demolish only the buildings’ interiors, while leaving the facades intact, using the nine buildings as a hollowed-out entryway for an 80,000-square-foot office tower.

It was only after Tavros started construction last month that the Department of Buildings discovered “dangerous preexisting conditions,” that merited the structures’ immediate destruction.

But the preservationists don’t believe that the Department of Buildings and Landmarks Preservation Commission’s determination was reached in good faith.

“This is a developer who clearly was most interested in building the office tower that was supposed to go up behind these nine historic landmarks,” Berman said.

“And these nine buildings were an inconvenience for that project… . But now, when they started that process, by some funny coincidence, they discovered that the buildings are in such bad shape that they can’t safely remain up and the city has said it’s O.K. to tear them down.”

Part of his disbelief comes from seeing that, “for the 175 years of their life, we’ve never heard about structural problems with these buildings.”

In fact, until recently they were occupied by rent-regulated tenants who, Berman told The Village Sun, have been relocated to a nearby building.

“While the L.P.C. and D.O.B. cited unsafe conditions, we know that workers have been seen eating lunch on this site,” said Lorna Nowvé, interim executive director of the Historic Districts Council. “Doesn’t that make you wonder: How great is the threat to public safety to warrant demolition?”

Zack Winestine, an activist with the grassroots organization Save Gansevoort, attributed the demolition to the “incompetence” of the developer and city agencies, arguing that “ full engineering reports” should have been conducted in advance of the planned interior demolition.

“I would propose that this spot be turned into a memorial park, memorializing the gap in New York City’s history, the gap in our neighborhood, the gap in the historic district,” he said.

Under immense pressure from the preservation groups, the two agencies in question agreed to meet next week with the preservationists and elected officials, including Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, Assemblymember Deborah Glick and state Senator Brad Hoylman.

“That doesn’t necessarily mean that they’ve changed what they’re doing,” Berman said in an interview with The Village Sun. “Meanwhile, they haven’t stopped the demolition of the buildings. So we don’t even know yet if this meeting will take place before the buildings are demolished or not.”

In its defense, the Department of Buildings and Landmarks Preservation Commission said in a joint statement: “The City must act quickly to keep the public safe when emergencies occur. Many of the structural failures, which predated the recent work at the site, were hidden by interior, nonstructural walls and surface finishes.”

But Berman said he’s seen buildings in much worse condition be repaired that “did not have to be brought down.”

Many at the protest expressed concern that the landmarked buildings’ demolition sets a bad precedent across the city.

“The city is colluding with developers to destroy historic structures,” Assemblymember Glick said. “It is not only a shame, it is disgusting… . In every neighborhood where there are historic structures, this city has sided with developers.”

“This is a cautionary tale for landmarked sites throughout the city,” said Nowvé of H.D.C. “What you see here is going to happen throughout the city.”

Developer Tavros Capital has committed to reconstructing the nine buildings, but the preservationists don’t want a “phony replacement,” as Diana Ducrose of Save Chelsea put it.

“A refabrication is very different then preserving a historic building,” Berman stressed. “We ideally do not want a sort of Disneyfied version of an 1840s row house.”

For example, he pointed out, the original nine buildings’ brick facades sport faded “ghost signs — painted signs from businesses that were probably located in the building 100 years ago or more.”

Village Preservation has documented the interior demolition of historic buildings in Lower Manhattan time and time again. Among them was 837 Washington St., in the landmarked Gansevoort Historic District, where a Meat Market building then owned by James Ortenzio, home to a row of refrigerated “meat lockers,” was gutted to create the Samsung 837 brand flagship building.

The tactic, sometimes called “facadism,” is one of the last-remaining loopholes after the sweeping 2019 tenant protection laws that can still be used to deregulate rent-regulated buildings. It can have destructive outcomes for both the buildings and the people living in them.

“Certainly,” Berman said, “the broader theme here is that this administration doesn’t care about historic buildings, doesn’t care about rent-regulated tenants and affordable housing, doesn’t care about neighborhoods.”

Hopefully the city won’t hold up the process to listen to these quacks