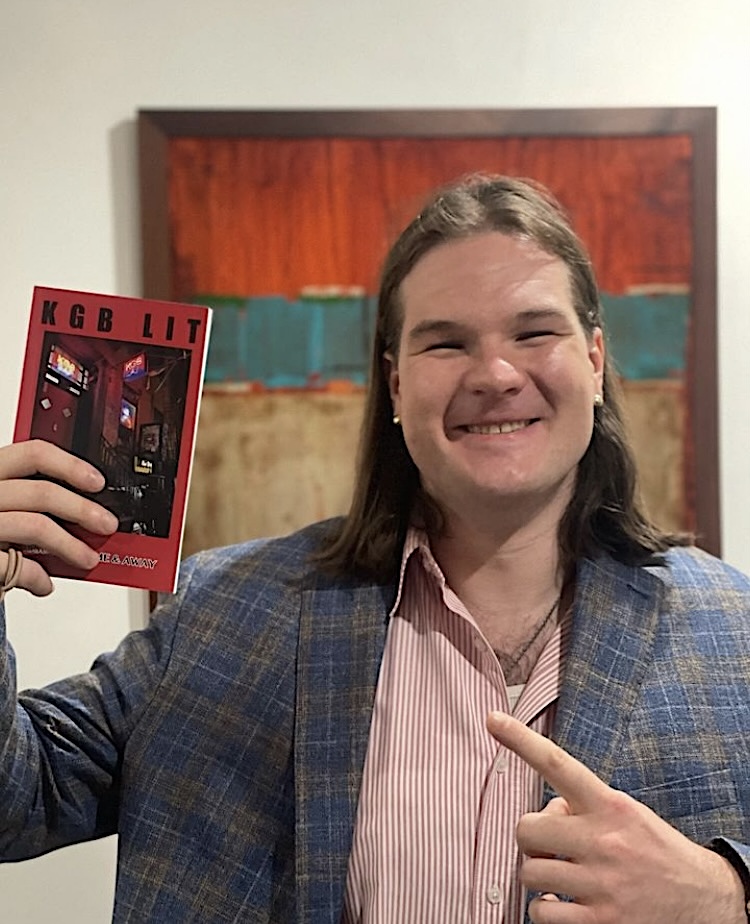

BY GARRETT OWEN | It’s 1:30 on a gray Saturday afternoon. Carrigan Miller is short on sleep. He bartended until 4 a.m. at the famous KGB Bar in the East Village. It’s just one facet of his relationship with the poetry-and-spoken-word venue on E. Fourth Street. He runs a quarterly show, along with being editor in chief of the quarterly KGB Lit, an on-again-off-again publication that’s existed in many forms since 2006. The name of the show is KGB Literary Magazine, though. Keep that straight.

The show is held on the second floor — the “Red Room.”

“That’s the golden ticket,” he says.

Big names have gone through that historic, red, Soviet-era, nostalgia-filled room over the years: Joyce Carol Oates, David Foster Wallace and Anthony Bourdain, to name a few. Always, the room is packed full of people. Each seat filled, stool bar stool sat upon, and every bit of standing room with someone squeezed into it. But Miller is new to this poets’ institution.

“I’m a ‘Johnny-come-lately’ to the scene, you know?” he admits.

The Minneapolis native is not a model for the average poet: broad shoulders and chest and thick arms. His large head looks molded by years of football helmets, which he wore plenty of when playing offensive line — left guard — at Macalester College. However, his face is unshaven stubble. He got that part right. His long, straight brown hair swishes around his head where his hat cuts off. His face pinches and his eyes become black dots when he laughs.

We’re ordering lunch at a restaurant in Murray Hill called Thai Food Near Me. It’s a great SEO shortcut for a restaurant. Carrigan orders a mixed vegetable Penang curry with chicken, medium spice. He throws in a double-shot iced Thai coffee. I order green curry with chicken and mixed vegetables. Appetizers? Hell, we forgot about those. Chicken curry pops, whatever those are. We add the cocktail deal. In my head, it is buy-one-get-one-free, and I order away.

I didn’t do the math.

“Eh,” he shrugs. “We’ll make it work.”

KGB Bar Lit released its second Miller-led issue in late October. Officially, it is titled, “Issue 18: In Movement.” It features prolifically published, award-winning poets, up-and-coming writers and eccentrics alike. His previous contributors have included writers and poets for the New York Times Magazine, Paris Review and a dozen other publications, domestic and foreign. With the newest issue out and finished, it’s time for him to start on the third issue. A typical timeline is about four months, with good reason.

First, he needs writers. For the two past issues, he contacted dozens of writers for their pieces. Now, writers he’s wanted to include have been reaching out to him. He’s proud of that, making him do a pinch-faced smile. The Thai iced coffee arrives. Miller scowls when drinking it but says, “Oh, man. That’s f—ing good,” raising it again.

Whomever he gets, he has to get to editing. The first round is “gentle.” He works with the writers on cutting and fixing things, changing what has to be changed. The next round is different.

“I’m blunt. Forceful!” he notes.

Anything to get things finalized. Then comes getting it on the Web site after the writer bios are written. Photos need to go up there, too. Then, outreach to customers and subscribers. Marketing. Advertising. This whole thing assumes that the writers are on time with their edits, info and bios. This has never happened. Miller then prints 100 copies. He sells them at the quarterly show.

Why print at all?

“It’s a perfect technology!” he says. “Pages bound!”

He excitedly praises the simple genius of Johannes Guttenberg coming up with movable type. (“No one’s improved on it!”) He badmouths the Kindle for trying. And Miller has a following of readers who are all about movable type.

“They want to hold the magazine,” he says. “They want the actual, physical thing.”

Those hundred copies aren’t cheap, either. It costs Miller $1,800 for the print job.

“I’m sure I’m doing it wrong,” he chuckles. “I’m very new to this.”

He looks away and gets a worried look on his face. He crosses his arms. He’s about to speak when food and drinks arrive. We divvy up our plates and take up our neon pink fruity cocktails.

“What are we cheers-ing to?” Here’s to it. “Alright, man, to it.”

The former lineman raises the pink drink up with a large, thick hand.

In any case, the magazine makes back most of the printing costs in sales: $1,300 for the last issue. That’s still a tough $500 hole in a devastatingly expensive city. He waves his hand, the other one holding a chicken curry pop.

“I can take the hit,” he shrugs. “If it’s like that two years from now, we’ll reassess. It’s a labor of love, you know?”

He fell into this whole endeavor by chance. It started with being in the Twin Cities. He worked in Minneapolis, doing “hard journalism”: writing economic news stories for the Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal, two 500-word pieces a day. Reporting on the stock ticker, S.E.C. filings and some healthcare pieces. He was near burnout after two years. Then George Floyd was murdered.

Minneapolis roared in the wake of that day in May. Miller was down in the streets, covering the protests and riots and chaos.

“Things were on fire,” he recalls. “I was running past the fires. I actually got shot at.”

He says he could hear the bullets coming in close. He says it seriously, and is proud of his reporting, doing his job when it all went down. He certainly sounds that way about the Business Journal: “We were the only paper in town saying he was killed.”

He’s wide-eyed and proud of that — the Journal getting as close to calling it a murder as it legally could. He sips his pink cocktail.

After this, he wanted something new. He wanted to do longer pieces with more depth. Reporting that belonged in a magazine. Miller found that hard to come by in Minneapolis. So, he looked east to New York. It made sense for him to look that way.

He grew up reading The New Yorker and Harper’s, passing around The New York Times Sunday edition at his nouveau-riche, family-of-lawyers’ breakfast table, he tells me wistfully. Reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’s New Yorker profile on rapper MF DOOM at 12 and Joyce’s “Ulysses” at 19. The literary scene back East always fascinated him. He laughs in a choppy, embarrassed sort of way. He shakes his head, which shakes his long hair.

“Sorry. I totally made you think I have bold artistic aspirations.”

Well, how many Midwestern former offensive linemen run a New York literary magazine?

He stammers and chuckles.

Back in Minneapolis, with eyes set on New York City, he had a stroke of luck: having the right neighbor.

“Yeah, well,” he shares, “I actually used to live in the same building as the [KGB] owner’s daughter.”

They became friends. He dog-sat for her. She helped introduce him to her dad. They exchanged numbers.

Things were coming along. Miller moved to New York City as a graduate student to study literary reportage at New York University, interning for Harper’s and graduating in 2023. He is philosophical, if cynical, about joining the program.

“You come into Lit Rep, not because your path is smooth,” he says. “You probably either don’t know what you want, or you do know what, but you don’t know how to get it. Or you’re a dilettante. Which is fine.” He admits to being somewhat of one himself. “I’m a snob,” he says. “For the same price as throwing axes for an hour, you can get the cheap seats at the New York City Ballet.”

Then, last winter, he got a text about a couch. KGB’s owner, Denis, texted Miller, asking if he needed one. Miller sure did; bought it off of him. The next week, he received another text from Denis asking if Miller knew anyone who could help get KGB’s semi-defunct literary journal back online.

“My entrepreneurial brain kind of turned on,” he says with a mouthful of Penang curry, “‘I can do that, Denis!’”

Miller grabbed the reins. He found writers. He made the cover, which he calls his “baby.” Still does, too.

He couldn’t pay the writers. Still can’t, either. He gets them published and reading time in the Red Room at KGB.

Miller loves it. It’s his show to run. But Miller doesn’t want to stay with KGB forever. What does he want to do long term?

“I want to run The New Yorker,” he says matter-of-factly.

He looks me right in the eye, with perfect confidence, and does not elaborate. I can see a Miller-led New Yorker being more artsy, more small-timers making it in, and all-around more pretentious but inspired.

We pass on dessert and get a check. I finish my cocktail, and Miller finishes his second. He has to get work on the next issue. Who knows? One day, it could be the next issue of The New Yorker.

For now, running KGB Lit is stressful enough. The timetables, the flakiness of writers and the frantic communications. He just had a major problem with the printing place he’s been using. They’re in Manhattan, and their lead times are just three days. This time, something got messed up.

“They nearly f—ed me,” he says.

A printing miscommunication led to the 100 copies needed on Thursday being scheduled for printing on Friday. A furious, profanity-soaked reaming over the phone from Miller on Thursday (where the kindest thing he told the printer might have been, “Listen, motherf—er!”) prevented a catastrophe, and the second issue launched at KGB Literary Magazine without further issue.

He’s happy to report, “I had my books at 6 for doors at 7.”

Be First to Comment