BY ALEX EBRAHIMI | Ever gone down Ninth Street feeling bad? Veselka’s line pouring out onto your feet. Conversation pouring out into your ears: “A bowl of borscht for Ukraine? But pancakes sound divine!”

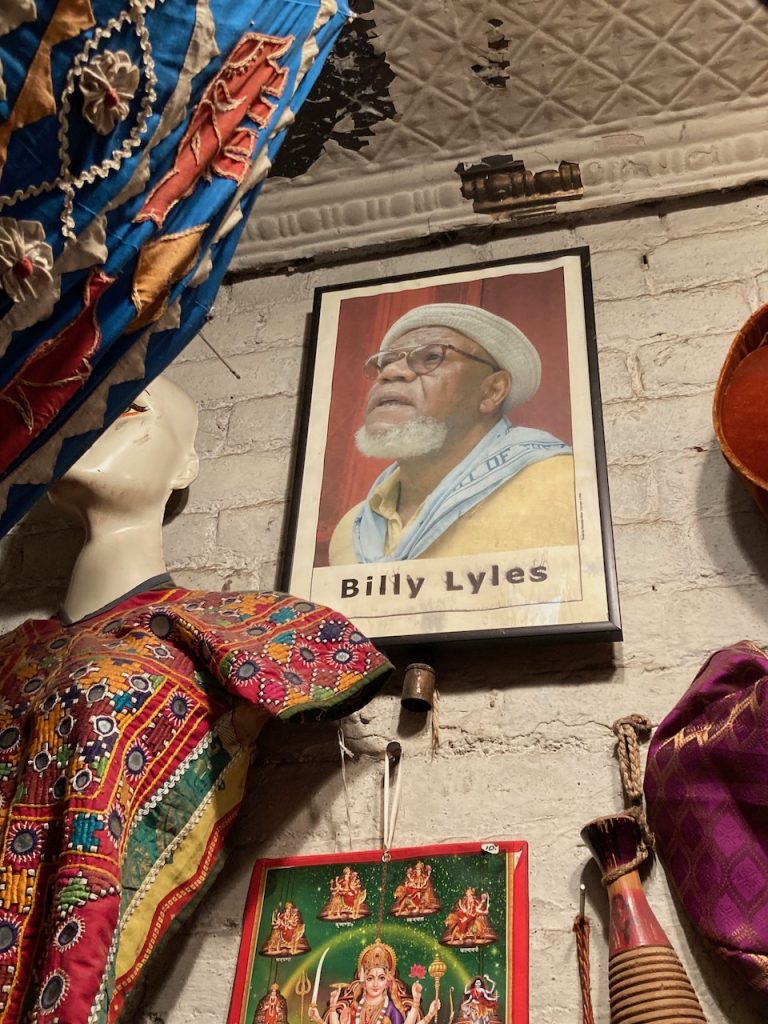

Ever crossed the street? To hear Billy Lyles sing the blues. To see what Jane Williams brought back from India. Ever wondered what “Katinka” means?

“An Airedale,” Billy told me as he swept up the storefront before opening.

“A what?” I asked.

“You know, the kind of dog Teddy Roosevelt had?” he said, switching brooms for the one he uses to sweep up the curb.

“Well, I know he liked dogs.”

“An Airedale’s a terrier, man. Beautiful dog. Jane always had that dog. Named Kate. Short for Katinka.”

Then setting down the broom with the other brooms by the trashcans outside. He let me know one last time before letting me inside the place: “It was a dog with papers, man! Now, follow me.”

Opening the door. Wind chimes sort of crooning. Bobby Sanabria on drums on the radio. There wasn’t much room to maneuver. But there was much to see on my part. And much to do on Billy’s.

“Man, it goes like this…,” he said as he picked up a box full of merchandise labeled $5.

“This is all Jane. I’m just the gatekeeper, see? That’s what I do.”

He shuffled back out the door with the $5 box. I followed him.

“Jane used to make things and sell them to Bloomingdales, Macy’s. Back then you could do that.”

“Her original designs?” I asked as he propped the $5 box against a neighboring stoop.

“Yeah, but what happened is…that was one thing. Then when she went to India, you get to work with the women and the fabrics and the colors and everything.”

He shuffled back inside, this time bringing out a chair faster than I could follow him.

“That way, rather than to be called just a designer…”

“She’s a teacher,” I said as he seemed ready to shuffle back inside again.

“A teacher and a…”

He meditated for a beat. Standing at the threshold.

“…ethno…,” reaching inside for another box labeled $10, “costume…,” bringing it out, “…ologist.”

Setting it on the chair he already brought out.

“You know what I mean?”

“Well…when’s she getting back?” I asked.

Before he could answer, the first customer of the 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. day came by. A self-proclaimed “walking advertisement.” Said she’s been coming by since back when the $5 box was the $3 box. The early days of Billy and Jane’s Katinka.

But the early days of Billy and Jane go back to a shop before Katinka.

“I think it was called Katinka, too,” Billy said.

Also on East Ninth. Also Jane’s designs. But no gatekeeper. Then in 1971: “I always stopped by and said hello and everything.”

Then in 1973, on Bastille Day in an old neighborhood place called “The Frog Pond,” Jane saw Billy again. Walking back and forth a few times till she got his attention.

“And the rest is history.”

But by ’73, Jane’s first Katinka was history, too. She hustled her designs around. And side-hustled by doing alterations around town. Billy hustled over between Lafayette Street and Broadway. Dressed in an Indian outfit and busking with a flute. Hustling enough money for a can of tuna and spaghetti for dinner for the two of them. Katinka, the second, didn’t open till ’79. Katinka, the dog, lived to 14 years.

“We were real tight, me and that dog.”

Then the second customer of the day came by. A dancer with a band playing on 10th Street later in the evening. In the meantime, as the rest of the band eyed the menu at Veselka, she was eyeing the earrings at Katinka. She picked out a couple. Billy handed her a mirror.

She thanked Billy, thanked Jane: “You know, Jane inspired me to go to India.”

“Good, good,” he said. “She’s there now.”

“Beautiful. Where?” she said, taking the mirror.

“Delhi. She’s in Delhi.”

“Beautiful,” she said, seeing how the earrings looked in the mirror.

“She’ll be back on…the 6th or the 7th.”

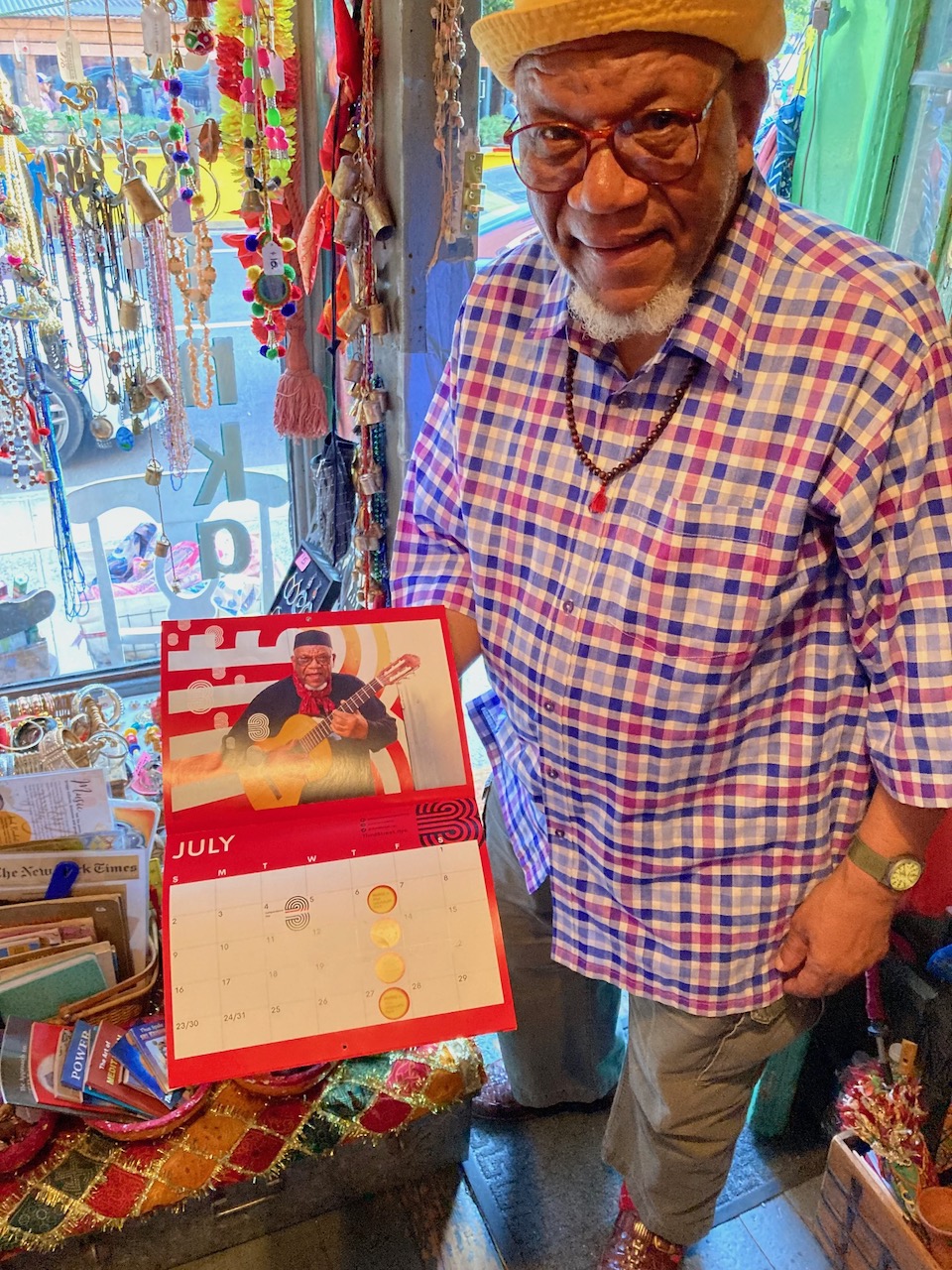

“You know, I’ve never seen you play.”

That’s because, as he told me, he plays when he feels like it. Just like the hours of the shop. It’s the kind of freedom he found when he first landed in New York back in the early ’70s. The freedom he first witnessed when he landed in Paris after serving in the Army, stationed in Germany back in the late ’50s.

Washing dishes at Gabby and Haynes in Montmartre, he witnessed the revolving door of Black expatriates. Many of them musicians. Many of them from New York. But one night hanging out in the Left Bank, it was what Art Taylor witnessed in Billy Lyles that changed everything.

“Art Taylor saw me struggling. He’s a hepcat. I mean, he could see.”

Taylor told him to go home. To study something. That’s what he did. And that’s when the searching started. First back in Washington, D.C., when he met “The Bard,” as Lawrence Wheatley called himself.

But Lawrence Wheatley wasn’t where the music started — just the part Taylor mentioned about “to study something.” The music goes way back home to the canon-booming backyard of Fort Pickett, Virginia. He was a 6-year-old country boy calling up june bugs under an oak tree while his grandmother tended the garden and his grandfather plowed the field.

“I was pretty smart,” Billy recalled. “I knew what I wanted to do. There was a lady, Miss Coleman. She used to play piano in the church. I knew I wanted to study with her.”

But he also knew that his grandmother had to go a long way to get up and down the road to church every Sunday.

“Not like we did when we went to the country store. We had to do that. But we couldn’t walk to Miss Coleman’s house.”

There was Miss Coleman in the country, Art Taylor in Paris, Lawrence Wheatley in D.C., and eventually Pharaoh Sanders in New York, and in ’69, he picked up a certain book called “On the Road.”

“I read it and I thought, man, I had to see that.”

The car he drove was a Nash Rambler. The destination was San Francisco. Freedom was on his mind. Searching was on the road. Singing and playing guitar everywhere he went. All through Indiana. All through Nebraska. Stopping in Boulder.

“That car wasn’t gonna go over them mountains. Just wasn’t gonna do that.”

Driving around and going across the Salt Flats. Coming down through Reno. Down through the Sierras. And by the time he arrived in ’69, he said, “Haight-Ashbury was a ghost town. I mean there was curtains flying out the windows.”

He should’ve known in San Francisco what he knew in Paris: “I belong in New York. Right here. I came here to do what I’m doing. To find my niche.”

And Jane. And the pandemic all these years later didn’t just threaten that toolshed between two buildings they converted into Katinka back in ’79. The world locked down just after one of Jane’s trips to India. She couldn’t return for five months. They talked on the phone every day.

“It goes like this…,” he said as he picked up a handy container of bird seeds. “I’m 81 years old now. It’s costing a whole lot more than it should. But if I had to do something else…,” he said, tossing the seeds from the shop’s wind-chiming threshold to the pigeons chiming in the gutter. “I’d probably find a wholesale district for flowers and sell flowers. Ain’t a bad business, if you know how to do it.”

“The flower business?” I asked as he tossed the last of the seeds.

“Damn right. But who knows?” he said, stepping back inside. “Maybe lightning will strike. You take care of today and tomorrow will take care of itself,” he said, as he sat down. He patted down the creases in the shirt he was wearing, which was made by Jane.

“Something good’s gonna happen. I don’t know what. But it’s gonna happen. It’s coming.”

“Jane’s coming back soon,” I said.

“Well, that’s always good,” he smiled.

Thanks for that. Really. I’ve had my chats with Billy (who tried to get me to take guitar lessons) but didn’t know all that about him!!! An important personality.

Lovely piece about a truly wonderful person, and an East Village institution. Billy is a genuine Love Love Love person. Just being around him can bring one closer to one’s own inner peace place. Thank you for the article!