BY CHRISTOPHER HIRSCHMANN BRANDT |

Handcuff. Etymology: you might think it derives from the same root as the teacher’s feared cuff, administered to the wayward schoolboy’s ear, that tuned his skull to the notes of a bell for an hour when he was twelve, or did it come from the cuff of a shirt, the finished end of a sleeve, that seems right. But no, it comes from the old English word cop, meaning fetter, a restraint. Synonyms: manacles, shackles, swivels, gyres — they turn but do not widen. We have Aristaeus, Apollo’s son, who was also the cause of Eurydice’s death, to thank for their first use, when he sneaked up on sleeping Proteus and slapped them on the shape-shifter, from whom he wanted apiary intelligence, by whatever means, and got it. The Industrial Revolution brought improvements in eighteen sixty-two and nineteen twelve, first the ratchet, then the swivel, then the swing cuff. Many stores in New York City sell them, including Party City, as they are often used in commercially negotiated domination sessions.

I knew none of that as Officer Vincent DiAdamo wrenched my arm behind me, threw me to the ground and tried furiously to smash my face into the pavement as he was calling for backup — “Officer in distress” — and two cruisers sirened from opposite directions and braked hard as cops leapt out, guns drawn, and I thought the next sound I heard might be a shot. One cuff snapped shut, then the second. Even at that adrenal moment, cuffed in all three meanings of the word, all I could think was, if I were black or brown I’d likely be dead.

Later, as I sat in the precinct holding cell, watching the cop fill out paperwork, as the angry purple blood drained from his face, Officer Vincent DiAdamo relaxed and explained to me, “Out in those streets ya gotta go a little berserk.” Then last week another Vincent DiAdamo threw another handcuffed man down and put a knee on his neck. Only that man was black, and after eight minutes and forty seconds of Officer Derek Chauvin’s full weight constricting his airway, suffocating, calling for his mother, choking out “I can’t breathe” just like Eric Garner, he was dead.

Still in handcuffs.

*********

RACISM AND MY WHITE PRIVILEGE

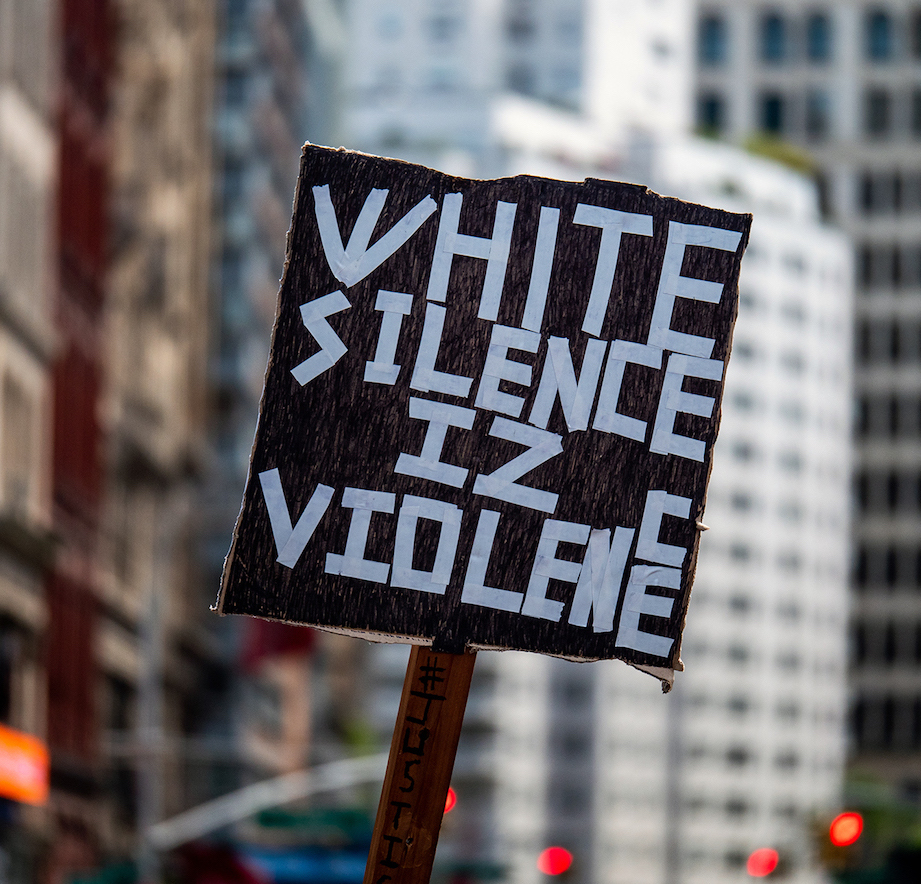

“The only reason for racism’s persistence is that white people continue to benefit from it.” And “Until white people call out white people, there will always be safe places for racial ugliness to brew and fester.”

Those two statements are by Bryan N. Massingale, a Catholic priest and a Fordham University professor. He is absolutely right. This is personal; the first white person I need to call out is — me. Until I do that, I have no right to speak of racism at all. So it’s time for me to list the benefits, general and specific, that I have received simply by being born with less melanin than my friend Anthony.

- I was never afraid of being arrested and charged with a crime I did not commit.

- I was never shot at by a cop or anyone else, just on suspicion because of my appearance.

- I have always been supported by family and social institutions which gave me access to an education where I was taught overtly that my country was one where “all men are created equal” — and simultaneously, in many subtle unspoken ways, that I was superior to people of darker skin tone (and generally to people who were poor).

- I have been hired for jobs, not turned down, because of how I look and where I went to college (since had I been black, I would have never even been considered for a place at Princeton.)

- I have been, and expect to be, listened to respectfully in public forums.

- I have always assumed it is my right to speak truth to power without fear of being beaten or shot at.

- Doubtless there are more, some of which I may still be blind to, but these will do for a start.

Those are the general ways I have benefited from the lightness of my skin. Now for some specific instances — or at least the ones I remember, since I am sure there have been plenty more I was never even aware of.

- A Racist Imitation: In high school, I lobbied for being allowed to do the daily announcements in a voice I copied from a popular comedian — José Jimenez. It makes me cringe now as I think back on a very bad imitation of a Mexican-American accent, my assumption that it was funny (it wasn’t), and the fact that many of the Mexican-Americans of Colorado Springs had lived for generations in the town we had moved to only a dozen years earlier. (The fact that the school administration not only allowed this but thought it was a funny idea in no way mitigates it.)

- A Joke in Commons: At Princeton, my student job was as a busboy in the Commons where underclassmen ate. One day when we were done setting up, I told a joke; mercifully, I cannot now remember it, but just as I had built up to the punchline, which was both racist and sexist (in this country’s classic combination), my listeners went silent and looked away. My back was to the entrance door, and thinking I was losing my audience, I put extra energy into the finish. No laughs. I turned and saw a classmate, Bob Engs, the only black student in our class of 620 or so. (The school was integrating.) For decades I tried to think of a way to apologize to my victim. Several years ago I googled him and found that he had become an esteemed professor of U.S. history (what else?) at UPenn. I wrote and rewrote a letter, then one day discovered he had died. So, no apology, and for whatever time is left me, I will have to live with that.

- Blackness and Sex: The first time I had a girlfriend who was African American, I was so proud of myself I could barely hold it in. But of course I did, since I knew it would not have been cool not to be cool about having a black lover. Proves I’m not a racist, right? (Just check that with any number of plantation owners who increased their own stock of slaves that way.) And there was the whole tangle of notions that black people are sexually freer and more passionate than us snow people. Took some time to realize that of course lots of people are attracted to others of different ethnicities, skin colors, languages; we are somewhere genetically programmed for that, it’s a way of constantly expanding the gene pool, so we are attracted to what — or whoever — is exotic in our eyes.

- The Joint in the Park: Once when I was quietly smoking a doobie on a park bench, a white cop accosted me and confiscated my joint but did not arrest me. I don’t even remember him giving me a ticket; I don’t believe he did. Had I been black, however, I could have been arrested, booked, charged, remanded to Rikers, and depending on my reactions and connections, I might have spent years in prison.

- Vinnie DiAdamo: In the late Eighties I was on the way home from a late rehearsal, and as usual there were many sidewalk vendors with their salvaged goods spread on blankets or sheets near the sidewalk curb. I was moseying along, looking to see if there was anything I needed, when a stocky police officer began kicking one vendor’s wares into the avenue; the vendor desperately tried to recover his goods before they got smashed by the traffic. I walked up to the cop, noted his name, Vincent DiAdamo, and said in a calm voice, “Excuse me officer, but you have no right to do that. You can tell him it’s illegal to sell here, but you have no call to destroy his stuff.” That enraged DiAdamo, and he countered that I’d better get lost, because he was in the habit of eating wimps like me for breakfast. I told him, good-humoredly, I thought, to go ahead and eat me, and from there things escalated until he was twisting me around and smashing me up against a bank window, then forcing me to the ground and trying to smash my face against the pavement as he called for backup. Two cruisers screeched to a stop seconds later, and four cops sprang out with guns drawn. Even then, I thought, “Man, I’m glad I’m not black, ’cause I’d be dead by now.” Later, as the officer was filling out the paperwork, I pointed out to him that his face had gone deep purple while he was screaming at me and trying to twist me in an anatomically impossible way. His response: “Oh yeah, yah gotta be berserk out there in the streets.” The fear that lay close beneath the hatred and the rage was obvious and deadly.

- CD Arrests: I have been arrested several times for civil disobedience actions, and though some of the actions have been spirited, and cops have sometimes clearly disagreed with the demonstrations, I have never been racially or ethnically assaulted or insulted. Black and brown comrades, however, have been.

- Doubtless, there have been other instances of white privilege in my life, but these will do for now, because they are pretty representative

So: I benefit every single day from the fact that I am “white” and male. Even in my radical political activities, I am taking far less risk than black, brown and Native comrades.

What this all adds up to is institutionalized white privilege. When we — “white” people — become aware of these advantages, the next step is crucial. If we accept our privilege without thinking about it, the racism gets baked in, whether we’re aware of it or not. Even if we do no racist actions, and speak no racist words. If, on the other hand, we not only accept it unconsciously but benefit from it, still unconsciously, for example, by buying a house in a redlined neighborhood where blacks are being forced out, that is white supremacy, whether we like it or not. (There’s a reason the process of becoming ethically aware is called “conscience-building,” concientización, among Latin American progressives.) If I support the racial inequities and think that is the right way for things to be, that goes beyond mere passive or unconscious racism; it is no different from Hitler’s “final” solution.

In the mid-Sixties, when I was first, stumblingly, becoming aware of such things, I was worried — “I don’t want to be a racist but maybe I am one, I have these thoughts… .” An African American friend back then very kindly told me, “Chris, since you have grown up in the U.S., what would be surprising is if you were not a racist.” That was perhaps the single most liberating thing anyone ever said to me. Yes, I am a racist because I have benefited so much and so consistently from our racist social structures. Whatever I can do to redress this inequality is a drop in a very large bucket — only if we privileged white folks put all our drops in, can we begin to change, to deal with our racism. Only if we begin to listen to our sisters and brothers, really listen to them, can we — together and following their lead — open our society to true democracy.

Brandt is a writer and political activist, also a translator, carpenter, furniture designer and theater worker. He teaches poetry and Peace and Justice at Fordham University. His poems and essays have been published in Spain, France and Mexico, as well as the U.S. He lives in the East Village.

Be First to Comment