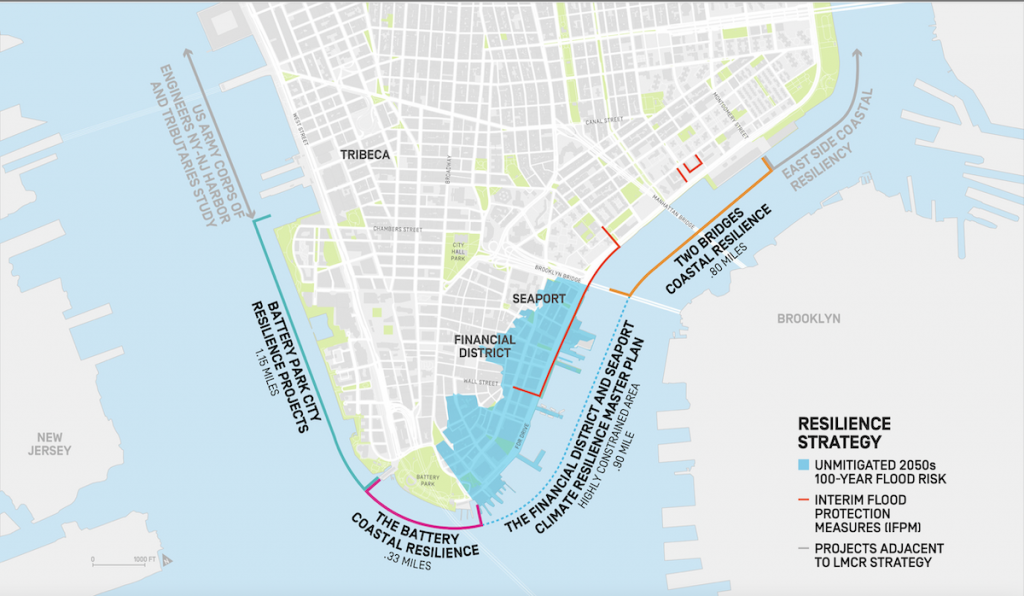

BY DASHIELL ALLEN | All across Lower Manhattan, from Tribeca to Two Bridges, a slew of coastal resiliency measures are being implemented — some more contentious than others — in order to protect the island’s southern tip from storm surges and rising sea levels.

Sea levels are expected to rise by about 6 feet by 2100, Jordan Salinger from the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice, told Community Board 1 on July 18. Coastal storms like Sandy will have an increased impact on the city; modeling is largely based off of preliminary 2015 insurance maps.

It’s no secret that some of these resiliency measures have been contentious. Just ask anyone that’s heard of E.S.C.R., short for East Side Coastal Resiliency, the city’s plan to bury the already-half-demolished East River Park and build it back at a higher elevation.

More recently, concerned residents of Battery Park City have questioned the need to raise (and raze) Wagner Park, calling for an “indefinite pause” to a plan that’s expected to begin in September.

These resiliency measures make up the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency plan, spearheaded by various state, city and federal agencies.

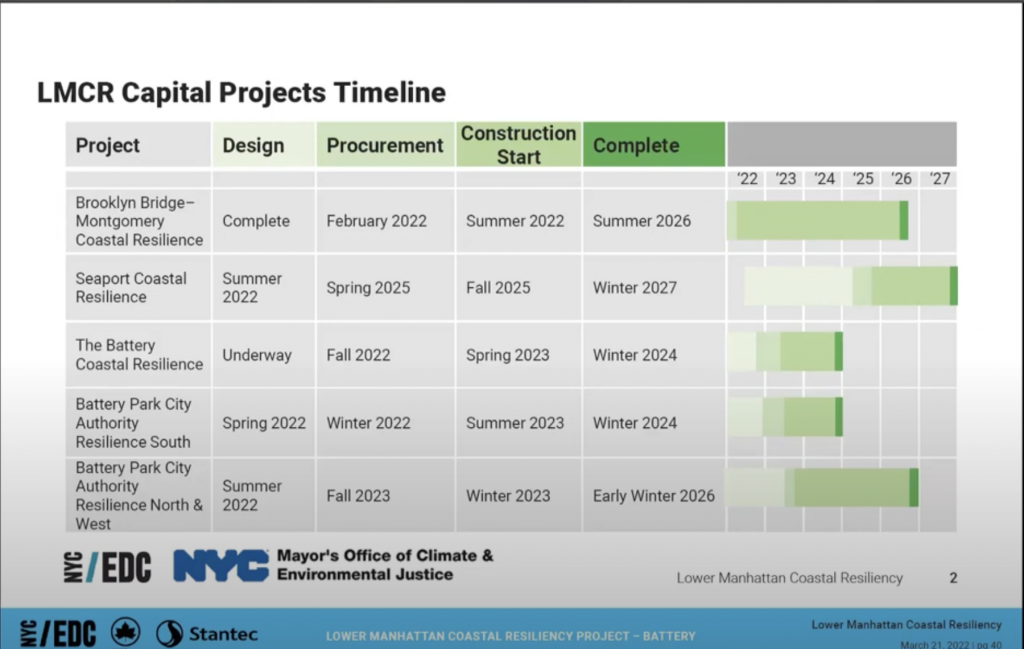

While some plans are progressing rapidly — think Two Bridges and Battery Park City — other key, low-lying areas, including Hudson River Park, north of Chambers Street, and FiDi, on the east, are likely to remain unprotected for at least the next decade due to a lack of funding.

Battery Park City

The Battery Park City Authority plans to begin demolishing Wagner Park starting after Labor Day weekend, as part of its $221 million South Coastal Resiliency project. Similar to as in the East River Park project, Wagner Park will be reconstructed at an increased elevation of 10 to 12 feet to protect against future storm surges and rising sea levels.

While the park itself did not flood during Sandy, a low-lying area directly to its east, referred to as a “pinch point,” did.

Since the planning process began in 2016 some changes have indeed been made to the initial park redesign, as demonstrated at a recent town hall presentation. But to Alice Blank, vice chairperson of Community Board 1, for the most part these have been minimal.

“It’s unfortunate with every one of these projects, where we are coming in well after the fact when the plans have already been instituted, and that’s continually a problem with participatory planning — there’s no public participation in the plan except to react to it,” she said in an interview.

A statement from C.B. 1 Chairperson Tammy Meltzer notes that, “CB1 repeatedly questioned the need to raze Wagner Park and the pavilion and is on record opposing this approach,” adding that, “It is crucial that all current and future work be phased to prioritize the areas with most acute need, located at the pinch points and lowest-lying levels, such as Pier A, Chambers Street and West Street.”

“If there was a design that the community liked and they understood, we wouldn’t be having this conversation,” said Britni Erez, a member of the Battery Park City Neighborhood Association, which would like to see an independent review of the plans before they start.

“The entire community wants a resiliency project that it would love and be proud of, and wants to work with the Authority to get there,” said Kelly McGowan, a 30-year resident of Battery Park City who was at the project’s initial planning meetings back in 2016.

Similar to East River Park, Erez doesn’t believe resiliency measures justify cutting down 112 trees.

In a statement to The Village Sun, B.P.C.A. Spokesperson Nick Spordone said, “Battery Park City’s resiliency infrastructure projects are not simply about this neighborhood — they’re an integral component of protecting Lower Manhattan. There is an urgent need for action due to more frequent and more severe storms, and through our years-long work with a wide range of City, State and local stakeholders, we’ve always prioritized community engagement early on and throughout the development of our resiliency efforts. We look forward to continuing this vital work to help protect our community from severe climate events for decades to come.”

In the midst of the contention surrounding Wagner Park, the Battery Park City Authority is in the initial planning stages for its north and west resiliency plans (estimated to cost $630 million), including Rockefeller Park, the once-future site of former Governor Cuomo’s beleaguered Essential Workers Monument. Those projects could kick off construction as early as summer 2023.

At an Open House on June 29, the Authority presented three potential alignments for each of the area’s seven sections, which connect to N Moore Street at the north and Wagner Park at the south.

An interactive presentation is available online, and the Authority is accepting comments through the end of the month.

Some proposals don’t include cutting down trees or raising the park’s overall height — at least not at the moment. Instead they contemplate building a network of flood barriers that would protect against storm surge but not necessarily against sea level rise.

“The disadvantage is that, in terms of especially the longer-term horizon, as flooding becomes more frequent and as storms become more severe, there is more risk associated with ultimate usability and accessibility of the park,” Gwen Dawson, vice president of Real Property at the Authority, told The Village Sun.

Plans that don’t involve elevating the park wouldn’t preclude it from being done in the future, she added.

“So, in some ways, it may be a question of: Do we do it now or do we do it in 15 to 20 years, will it be harder to do then?”

Battery Park

Directly to the southeast of Wagner Park, the city’s Economic Development Corporation is undertaking a $165 million resiliency plan for Battery Park, which is expected to break ground in 2023. Unlike the other projects, it doesn’t involve cutting down trees. Instead the plan involves raising the park’s esplanade by 5 feet, enough to protect against sea level rise but not coastal storms. Storm surge protection would be added separately through the completion of the unfunded FiDi-Seaport Master Plan to the project’s east, and to the west through a tie-in with the South Battery Park City Resiliency project. Construction should start in spring 2023.

The Battery plan is largely not facing major opposition. However, Blank and other community board members question why its goals — to protect against sea level rise yet not storm surges — are different from surrounding projects.

“Is the idea that the Battery would be sacrificed in a future storm moving forward?” she asked at a July 18 board meeting. Agencies representatives, attempting to skirt the question, ultimately answered yes.

Brooklyn Bridge-Montgomery Coastal Resiliency

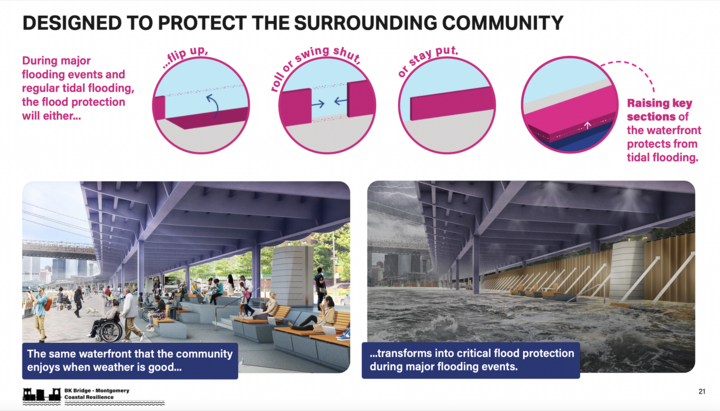

In the Two Bridges section of the Lower East Side, the $522 million Brooklyn Bridge-Montgomery Coastal Resiliency (B.M.C.R.) plan, funded by the city and federal governments, will elevate a portion of the East River promenade, installing flip-up and roller flood gates that would flip up in the event of a storm. The plan also adds new community amenities, plus improves sewer and drainage infrastructure. Construction should begin in the fall.

The section of the East River esplanade under the F.D.R. Drive isn’t exactly green, luscious parkland, but it’s heavily used in the evenings by the working-class and immigrant communities in the surrounding area.

Portions of the esplanade are already roped off due to disrepair, and tidal flooding is a daily reality. Tiger dams, a form of interim flood protection, surround the Al Smith Houses, a New York City Housting Authority development at heightened risk of flooding.

All of the above serves as “a direct reminder of your vulnerability every single day that you look out of your window and go out of your home,” said Frank Avila-Goldman, a resident leader from nearby Gouverneur Gardens, a Mitchell-Lama co-op.

The HATS Study

Resiliency to the north of Battery Park City remains a looming question mark. No plans are in place to address storm surge or rising sea levels at Canal Street, a low point that really once was a canal in colonial times, or in Chelsea, which suffered heavy damage during Hurricane Sandy.

The area is included in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ New York/New Jersey Harbor & Tributaries Focus Area Feasibility Study (often shortened to HATS), a multiyear analysis of how best to achieve resilience throughout the entirety of the two states’ shorelines.

The study was paused for two years starting in 2019 after then-President Trump cut its funding. It restarted this January.

Bryce Wisemiller, a project manager, confirmed that the Army Corps is scheduled to present a “tentatively selected plan” in late July and release a “draft feasibility report” in late September. Next the Army Corps will begin a 60-day public review process. A final report could be issued as early as June 2024, though any plans the Corps proposes would require the approval of Congress or state and city agencies to fund.

An early cost estimate presented by the Army Corps at a February C.B. 1 meeting put the price of resiliency for the region at anywhere from $62 billion to $10 billion. At that same meeting, Wisemiller acknowledged that any plan involving closing down all waterfront parklands at once would be “a nonstarter.”

Kate Boicourt, director of NY-NJ Climate Resilient Coasts and Watersheds at the Environmental Defense Fund, is following the HATS study closely. She’s advocating for a phased approach that would take into account the “multiple hazards,” from heavy rain events like Hurricane Ida, storm surges and rising sea levels.

One of the HATS study’s potential plans, presented in a detailed interim report from February 2019, is to build a gargantuan storm barrier across outer New York Harbor, extending from Sandy Hook to Breezy Point.

Boicourt described this as “putting all of your eggs in one basket for only one of the problems that we have,” since it would only protect against storms like Sandy.

“This is not a solution we need right now,” she added. “We’re trying to get that study to be a phased approach, so that we have the near-term thing, that whatever plan comes out of it, the Corps does it in a way so there’s an option for near- and long-term.”

The short-term concerns are very real, Boicourt assured.

“Canal street used to be a stream, and if you look at the future high-tide line, and especially when you look at the future flood plain and even the current flood plain, you can kind of see that history there,” she said. “That’s true with a lot of New York actually.”

A representative for the Hudson River Park Trust told The Village Sun in a statement, “A floodwall system, like that proposed for Battery Park City, would not be feasible for the entire 4-mile length of the park and the park’s many long, narrow piers.

“There are no plans to raise any [Hudson River Park] piers that have already been built; piers have to meet the elevation of the historic bulkhead at their eastern ends, and the adjacent highway drainage system also relies on certain elevations,” the statement continued. “In some cases, we have been able to elevate new sections of park that have not already been built, like the ball field under construction now at Gansevoort [Peninsula].”

William Benesh, a member of Community Board 2, personally wants to take a more proactive approach to protecting the Lower West Side.

“It’s up to us as a community to envision what resiliency looks like in our district,” he said. “But as far as the sequencing, we’re behind what’s been happening in the other community boards. During Sandy, during some of the more recent storms that we had, there’s obviously flooding in our district, as well. I think perhaps if I had to guess…probably the complex set of agencies make it a little difficult to start.”

(The waterfront park is under the jurisdiction of the Hudson River Park Trust, a state-city authority. The West Side Highway belongs to the state Department of Transportation. The Hudson River bikeway is also under the purview of D.O.T. — having been built as part of the highway project — though is maintained and overseen by the Hudson River Park Trust.)

“You don’t want a situation where the city is just saying this is what it’s going to be and that’s it,” Benesch said. “I think if the community is out there and we are expressing our voice, that’s our idea.”

He’s already built relationships with members of Community Boards 1 and 3, hoping to leverage their greater level of experience on resiliency matters.

FiDi-Seaport master plan

On the eastern side of Battery Park, the Financial District and South Street Seaport, two acutely low-lying communities, remain largely unprotected, save for a $5 billion to $7 billion, currently unfunded “master plan” that could be completed within 15 to 20 years, at the earliest.

The hypothetical plan, released at the end of last year by E.D.C., would extend and elevate Manhattan’s shoreline, making use of natural features, such as marshes and wetlands, for protection.

The master plan notes that “existing government agency structures may not be ideally suited to manage a project of this scale and cross-disciplinary nature. Instead, a special-purpose entity could bring these disparate functions together under one roof with specialized staff and a clear mandate.”

This plan is almost like a late-stage adaptation of former Mayor Bloomberg’s much-criticized scheme to build a Seaport City, complete with luxury high-rises.

The master plan states: “Building residential and commercial developments on the East River extension is unlikely to contribute significantly towards the capital costs but could provide a significant share of annual O&M [operation and maintenance] costs.”

And when the money runs out?

“The money is where a project will go, and the community’s opinion on it is somewhat secondary and after the fact,” noted C.B. 1 Vice Chairperson Blank.

That point is echoed by Wendy Chapman, co-chairperson alongside Blank of the C.B. 1 Environmental Committee.

“Everyone is protecting their own block and their own property because they have the money,” she said. “Well, who doesn’t have the money? It’s the residents and the city themselves. We don’t have a sense of the collective.”

That might explain — at least, in part — why Battery Park City, which is home to the world headquarters of American Express and the investment banking firm Goldman Sachs, has the financial ability to take on large-scale resiliency projects. The Battery Park City Authority also has the ability to issue bonds.

Next door, the World Trade Center campus secured $112 million for street-level flood-protection measures from the Port Authority back in 2015. The Javits Center, up in Hell’s Kitchen, has taken similar measures.

The Seaport is currently protected by interim measures, and the city is spending $170 million to raise its esplanade from between 3 feet to 5 feet. The city is also betting on a $50 million Federal Emergency Management Agency grant that it applied for here — yet the crux of its plan remains unfunded. Work won’t begin until at least 2025.

Across the city, entire neighborhoods await resiliency funding. East Harlem, for instance, is at high risk for flooding and coastal storm surge based on flood maps.

The low-income largely Black and Hispanic neighborhood was spared from Hurricane Sandy thanks to a timely low tide, but it might not be lucky next time. Following Sandy, the city created a Vision Plan for a Resilient East Harlem.

After the local community board filed a Freedom of Information Law request for the plan, it was given a heavily redacted copy, with an understanding that the critical part of the scheme wasn’t economically feasible.

“Pretty much everything we were being presented, in terms of solutions, was somehow impossible, whether it was the funding required, the coordination of different city agencies, the impact to traffic, the drainage systems,” said Jessica Elliott, the vice chairperson of Community Board 11.

The city’s Parks Department is planning to raise the Harlem River esplanade, part of completing a continuous Manhattan greenway. But without proper drainage, doing so could leave the neighborhood even worse off, creating a bathtub effect that would cause rainwater to flood the neighborhood. The community doesn’t have the resources to fund a million-dollar plan independently.

Comprehensive planning needed

Practically every person The Village Sun spoke with, regardless of their opinions on particular projects, agreed there needs to be comprehensive, centralized and community-led participatory planning in order to achieve coastal resiliency citywide.

“We’ve got this tremendous challenge and we need to address it. But that is no excuse for not having a good process,” said Boicourt of the Environmental Defense Fund. “The government needs to make sure that they’re being transparent…and that every decision that’s made to include or not include something is backed up with a reason and told. And I think that’s one of the challenges that communities have found in New York — that they’re not getting the full story.”

She’s hopeful, though, that government will ultimately get it right.

“We’ve been advocating for the establishment of a chief resiliency officer and statewide resilience plan,” she said. “I think there is a lot of planning that needs to happen. We’re not quite there yet.”

To its credit, the city has taken some steps, such as passing a bill last year requiring the release of a “citywide climate adaptation plan” (due this September), and releasing a massive Comprehensive Waterfront Plan, which, however, doesn’t discuss Lower Manhattan in detail.

“No two projects across [the city’s] 520 miles of coastline will look the same,” Jordan Salinger from the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice told C.B. 1. “Just because on the surface the projects don’t look the same doesn’t mean the thinking isn’t consistent across all of these projects.”

True community engagement

“Authority staff and other members of the project team have participated in each of the 34 public meetings [and] engaged in productive, two-way dialogue on these important issues,” the Battery Park City Authority wrote in response to a list of questions submitted by the neighborhood association.

“To suggest otherwise — that public engagement on this project has been ‘predominantly one-way dialogues presenting a summary of top-down decisions to a small segment of the community’ — is both inaccurate and, based on the ample evidence to the contrary, misleading,” the Authority said.

Nevertheless, Kelly McGowan, who participated in many of those meetings, said the outreach simply was not sufficient.

“It doesn’t matter if you had three meetings or 30 meetings or 300 meetings,” she charged. “That’s not community outreach if the people who use [the park] every day two months before you’re supposed to break ground aren’t aware of the impact.”

Mia Marais, a Battery Park City resident who spoke with The Village Sun in Wagner Park, recalled she heard about the resiliency plan six months ago, through “rumors and other people mentioning it.” However, she only recalls receiving official notice about it from the Authority a few weeks ago.

Ana Maria, who lives on E. 12th Street and frequently rides her bike in the park, hadn’t heard about the plans, despite standing directly in front of a sign describing them. She ultimately was in support.

“If it’s such a positive project, I agree,” she said. “New Yorkers, we love to have what we have and we don’t like to go through change but this is necessary.”

“A lot of residents don’t even know what a community board is,” said Wendy Chapman, who is herself a Community Board 1 member and supports the Wagner Park plan. “I didn’t know about it until my kids were in school.”

“You don’t want a room just of people that are going to make it their business to attend regardless,” said Frank Avila-Goldman, referring to resiliency in Two Bridges. “Community board meetings around BMCR [Brooklyn Bridge – Montgomery Coastal Resilience] need to be held directly in the affected neighborhoods.”

Added Avila-Goldman, “It’s a turnoff when you go to meetings, and these meetings are hours long and the logistics aren’t worked out with the translation communication.”

Chapman is convinced the best way to reach the public is by physically standing in the park, handing out fliers and talking to neighbors. Thanks to her advocacy, colorful signs now dot Wagner Park notifying residents of the green space’s impending demolition.

Across the southern tip of Manhattan, people are starting to band together: In the Two Bridges area, leaders from the Smith Houses, by the Brooklyn Bridge, and the Baruch Houses, just north of the Williamsburg Bridge, have formed the Lower East Side East River Residents Committee.

“We want to make it our business to share information with each other as leaders and engage each other and share resources for our residents,” Avila-Goldman said, “because our communities are too often overlooked.”

Meanwhile, Battery Park City resident Britni Erez is forming a “Green Coalition” made up of groups from various neighborhoods, including Soho’s Broadway Residents Alliance. The group is calling for “prioritization of the most at-risk and vulnerable areas first,” and “integration across jurisdictions and neighborhoods, as water knows no boundaries.”

“You can’t think of green spaces in isolation,” Erez said. “People in Lower Manhattan travel far distances to access green spaces.”

Steve, I am a registered tree pruner with the Department of Parks. In addition, I know the size of 50-to-100-year-old trees. My family has had a house Upstate for 70 years and they have planted many trees on the property. I don’t care what the web site says — 50-to-100-year-old trees take 50 to 100 years to grow to the size (height and fullness) of the trees that are being destroyed. Planting 1,000 saplings and considering that sufficient is a joke.

You are surely a “plant” from the real estate industry. Who else would think cutting down these trees was a good idea?

Steve, replacing 50-to-100-year-old trees with saplings is not going to help either this or the next generation.

The original plan APPROVED WITH COMMUNITY INPUT called for an eight-foot wall between the park and the FDR. And in fact the City is now delivering huge WALLS to the more affluent neighborhoods, such as Kips Bay.

Carol, trees grow pretty quickly. Seriously, they do, google it. And a 3-inch-wide tree sapling may sound small but that tree is about 15 feet tall. Those 80-year-old trees in East River Park didn’t just get to be that size recently. The idea that this generation or next won’t benefit from the trees is completely incorrect.

This shows what all the different species will grow into in 20 years, but a lot of this growth happens in the first five:

https://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2016/09/DES-Stormwater-Appendix-E-Tree-Canopy-Requirements.pdf

“Practically every person The Village Sun spoke with, regardless of their opinions on particular projects, agreed there needs to be comprehensive, centralized and community-led participatory planning in order to achieve coastal resiliency citywide.”

Centralized and community-led are inherently at odds with each other. Something that is community led can’t be centralized because there are multiple communities that are dealing with these issues, as the article sets out. Something that is centralized and comprehensive can have community input, but it can’t be community-led because ultimately the central planner has to make decisions and there will be trade-offs. How do you, or the people interviewed reconcile this? It seems like they are demanding something that could never be achieved.

Good article, thank you. However it is important to point out that resiliency measures that include killing established trees are not truly resilient. We cannot continue to view climate change projects in this siloed, either/or way or we risk exacerbating the impacts of climate change, such as the heat island effect.

Climate change is not just about storm surge and sea level rise. We are experiencing increased heat everywhere. Removing all the trees at the waterside, which is essentially what is happening, is deforestation of our urban forest, and we need our urban forest. The older the tree, the more it does to protect us from flooding pollution etc.

600 to 700 mostly mature trees chopped down and mulched in East River Park and Corlears Hook Park and now the same scenario planned for Wagner Park and Fort Greene park is an inadequate and immoral approach to resiliency.

🌳💯💯🌳

You’re missing the forest for the trees. All these plans include replacing lost trees and usually a lot more than were removed. Every one.

Please replace the trees .