BY BONNIE ROSENSTOCK | Local historian and ethnomusicologist Jose Pepe Flores inaugurated La Sala de Pepe (Pepe’s Living Room) and Foto Espacio (Photo Space) in December 2021. In doing so, he realized a longtime dream of presenting salon-style workshops and conversations with community leaders, scholars and musicians from the Hispanic diaspora and contemporary Latinx community.

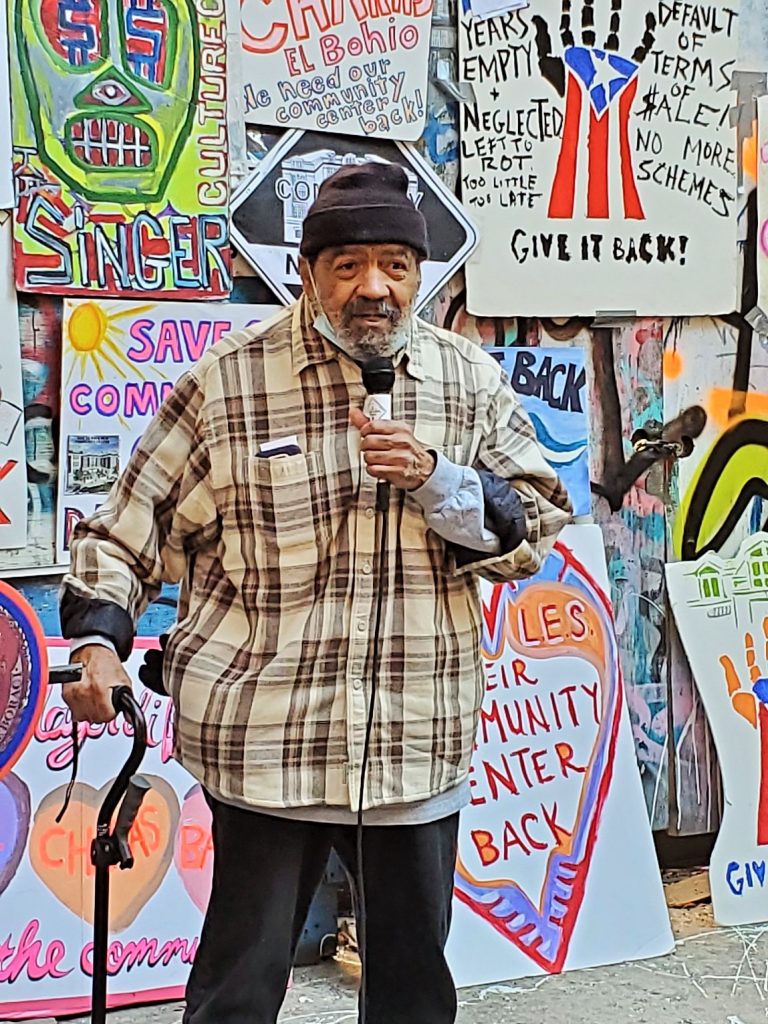

On May 25, as part of Lower East Side History Month, the storefront at 73 Avenue C (a.k.a. Loisaida Avenue), between Fifth and Sixth Streets, was host to “Loisaida Legends,” in which Flores; iconic community activist Carlos “Chino” García, founder of CHARAS/El Bohio Community Cultural Center; and Lyn Pentecost, founder and director emeritus of the Lower Eastside Girls Club, recounted their experiences of activism on the Lower East Side in the 1960s onwards.

Flores welcomed the overflowing crowd to his “simple but elegant space we have created in the heart of Loisaida,” and acknowledged that it was influenced by García and CHARAS.

“There were all kinds of free cultural events there,” Flores said.

Also addressing the enthusiastic audience was Alejandro Epifanio, “a newbie,” he confessed. Since 2014, he has been the executive director of the Loisaida Center, at 710 E. Ninth St., at Avenue C. He was one of the co-producers of this year’s 35th Annual Loisaida Festival on Sun., May 29.

“I am honored to be sitting with the true legends of this neighborhood,” Epifanio said. “In my time at the Loisaida Center, I have had the benefit to talk at length with Chino and Pepe about their experiences in the history of the neighborhood and the impact that Latinos, Puerto Ricans, artists, activists and cultural producers have had to preserve the cultural fabric and vibrancy of the neighborhood, which is still strong and getting stronger. An example is La Sala de Pepe and Piragua, and I hope many more will come.”

Speaking via video feed was Herman Hewitt, the owner/broker of H.F. Hewitt Realty, located at 291 E. Fourth St., one of the first Black-owned businesses in the neighborhood. He’s also the board of directors president of the Lower East Side People’s Mutual Housing Association. Hewitt is also on the Economic Development Committee of Community Board 3, of which he was a longtime vice chairperson.

Musician David “Daso” Soto presented his music video “Jengibre” (“Ginger”), featuring his mother, the legendary María Angie Hernández, a community activist since the 1970s with the Grupo Cemi, child actor Emperor Kaioyusa and himself. The upbeat music was written by Daso and William Millán of Conjunto Saoco.

Daso, organizer of the annual New Village Music Festival in Tompkins Square Park, opened Piragua Art Space, at 367 E. 10th St., between Avenues B and C, on May 1. In Puerto Rico, piragua refers to shaved ices covered with fruit-flavored syrup. He told me that he named his cultural center in honor of “los piragueros,” Puerto Ricans, who found a way to earn a living when they came to New York when no one would hire them.

The gathering was co-sponsored by the Cooper Square Committee, EVIMA (East Village Independent Merchants Association) and LES.sba (Lower East Side Small Business Alliance), which was co-founded by Frank González, who is also co-founder of the nonprofit LES CommUnity Concerns and owner of Loisaida Realty. The event was moderated by Jimmy Carbone, a restaurateur and former owner of the popular Jimmy’s No. 43 on E. Seventh St. in the East Village. The food was supplied by Casa Adela, the legendary Puerto Rican restaurant across the street from La Sala de Pepe.

Flores recounted that he moved to the Lower East Side from Puerto Rico 60 years ago when he was 20. He currently lives above La Sala, but got his first apartment through García for $75 a month.

“We were interacting in lots of ways,” he said of the two other luminaries. “Chino was in housing and culture, Lyn was in education, and I was in daycare.”

As such, Flores worked at Children’s Liberation Daycare Center for 35 years as a preschool classroom teacher. (The building on E. Ninth Street and First Avenue now houses Performance Space New York.)

In addition, Flores was engaged in affordable-housing issues, community gardens and public spaces. He is also recognized as one of the premier authorities on Latin music, as his 10,000-plus record collection will attest to, archived on shelves in the back room of La Sala.

García spoke about the youth gangs, saying, “We organized ourselves around social issues and political action as groups.” His gang, The Cheyennes, changed their name to the Real Great Society “because President Johnson had the Great Society. We were concerned with crime and housing that affected the people in the community.

“The ’hood wasn’t developed like it is now, and it was a really rough neighborhood to live in,” García recalled. “You had to look out for yourself and other people. The youth gangs we formed were for protection, not for crime. We were pretty strong and well-organized, with a few hundred people.”

In Chelsea, where he had lived before, his gang was The Assassins, with their main headquarters on W. 22nd Street, a Puerto Rican neighborhood at that time and a very tough area. His parents applied for housing, and they moved into the Baruch Houses at Avenue D and Houston Street.

“In my new neighborhood, we had to deal with The Dragons,” he recounted. “We also dealt with the police and social agencies; you had to deal with everybody because everybody had something to say.”

Some of their projects were groundbreaking because they were the first ones to do it, especially the idea of “sweat equity.”

“Nobody ever talked about it” García said. “We found an empty building and renovated it ourselves. Years later, Habitat for Humanity came to us and asked us, ‘How did you do that? We would like to start building.’ They did two buildings on Sixth Street. It was the beginning of a national movement.”

They were also the first to initiate solar energy and wind power design for tenement buildings anywhere in the world.

“It helped changed laws in the U.S,” García declared. “The ideas came from a neighborhood that people didn’t think much of. A lot of youth gangs in other cities also wanted to learn from us. It was a youth movement we created. If you can do it, we can do it. Ideas got spread out and carried out by thousands across the country and in Puerto Rico.”

When the McClellan Committee (1957-1960) — a Senate committee set up to probe labor-management relations — questioned people who donated money to the Real Great Society, however, it interfered with their fundraising and organizing. They still garnered some funds, but they were operating on a shoestring. They changed their name to CHARAS, using the first letter of each of the organizers’ first names: Chino, Humberto (Crespo), Angelo (González), Roy (Battiste), (Moses) Anthony (Figueroa) and Salvador (Becker).

“We later found out that in India ‘charas’ means ‘marijuana,'” García quipped. “We had nothing to do with weed.”

Working-class people still live in this neighborhood — Latinos, Blacks, poor whites and others — because of the housing-movement groups that were created throughout the years, García explained.

“We started putting pressure on the government to save some of this land, and we succeeded, like the buildings across the street [from La Sala],” he said.

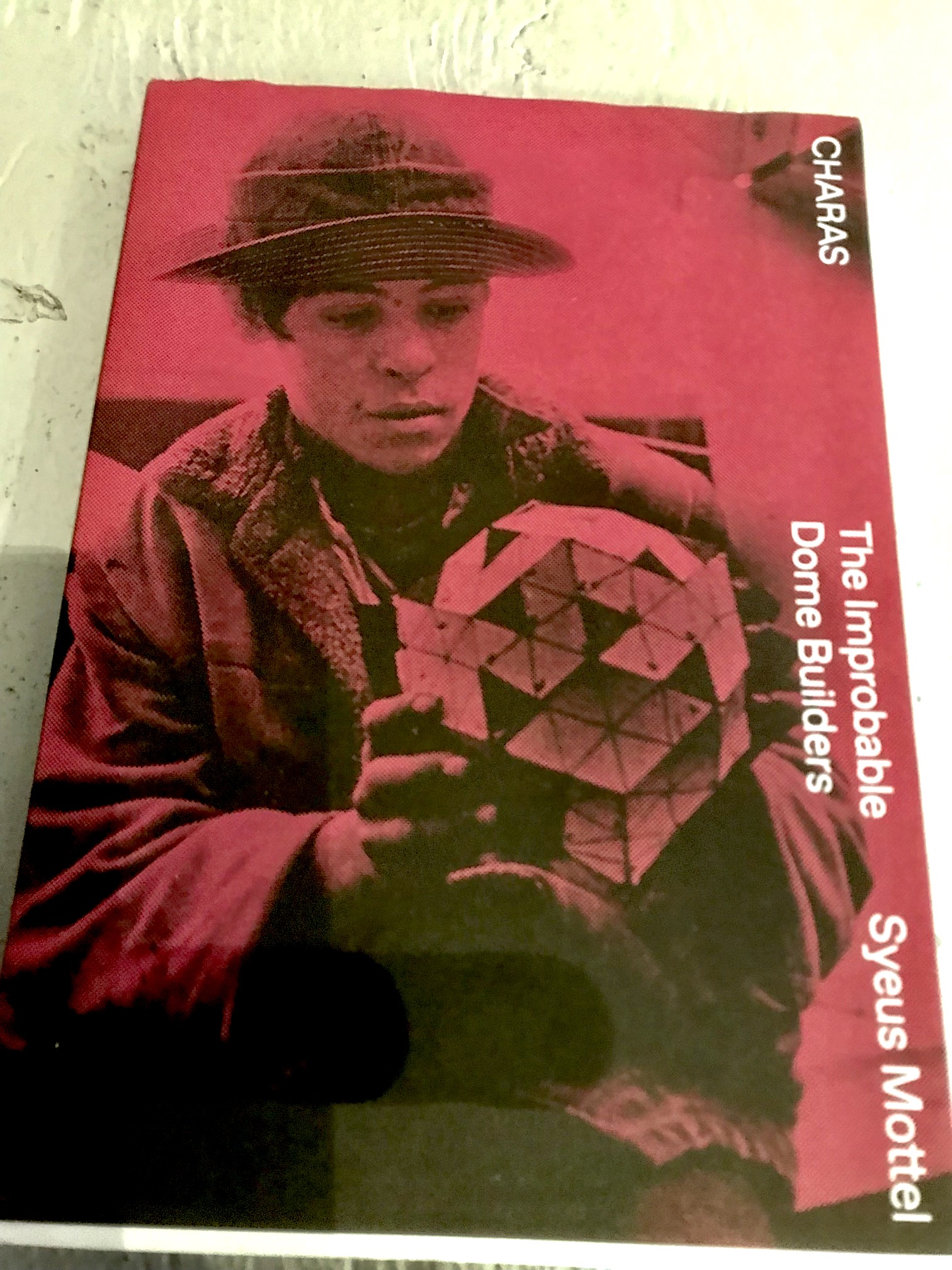

Pentecost interjected that she discovered a book, “CHARAS, The Improbable Dome Builders” (originally published in 1973; republished 2017), by Syeus Mottel, when she was at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., a few years ago, and passed it around. The book tells the story of how García’s crew broke ground to construct a geodesic dome on a vacant lot after meeting with Buckminster Fuller.

García mentioned that they were the first group to open public green space — at E. Ninth Street and Avenue C — on the Lower East Side, in 1976.

“We took the biggest lot that was empty at that time, called it La Plaza Cultural…” he said.

After Armando Perez, CHARAS’s artistic director, was murdered in Queens in 1999 at age 51, the garden was renamed La Plaza Cultural de Armando Perez in his honor.

“Armando was a very strong leader,” García recalled of Perez, who was also a Democratic district leader.

In fact, Liz Christy Community Garden, on Houston Street between Bowery and Second Avenue, founded in 1973, was the first community garden in New York City. The late Liz Christy herself gave García a willow tree, which he said is still thriving in La Plaza.

In 1979, Charas moved into the derelict old P.S. 64, at 605 E. Ninth St., between Avenues B and C, just down the block from La Plaza. They renovated and operated the the place until 2001, when the new owner, Gregg Singer, evicted them. Singer had bought the building for $3.15 million at city auction in 1998.

Two decades later, the former school building remains abandoned and is deteriorating. CHARAS is hopeful that the new administration will return it to them.

Pentecost quipped that while García was with the youth gangs, she was with the “art gang.”

“I went to Cooper Union in the late ’60s,” she said. “People were really innovating and re-creating the social-justice movement. I was doing it in the arts. We met the gang around the corner, which was CHARAS and the Real Great Society. We were artists and future architects. We soon became ‘backup singers’ for Chino’s projects.”

She holds degrees from The Cooper Union (bachelor of fine arts) and Temple University (master of arts in visual anthropology and Ph.D. in urban anthropology).

“In 1968 Cooper Union gave us a lot of money, with the help of the Rockefeller Foundation, to open a community arts center in an abandoned building at 523 E. Sixth St. and Avenue B, and we created the Children’s Art Workshop,” she recalled. “We took the first two floors and created a community darkroom for teenagers and silk screen and graphic arts and print shop in the basement. At night, we would print for the Young Lords and Black Panthers.”

Her group also rented a storefront across the street from the Children’s Art Workshop to open a photography gallery, the first of her four.

“During that time, we met a lot of poets, like Miguel Algarín, his partner Richie August, Miguel Piñero, etc.,” she said. “They needed a place to live. It was a railroad apartment with the gallery in front, so we put them in the back half, and that’s where the Nuyorican Poets Cafe was born. They eventually rented a spot down the street.”

Pentecost’s group started the Lower Eastside Girls Club “with nothing but a shopping cart full of supplies, books and art supplies,” she recalled. “We didn’t have a home at the beginning. We set up at Middle Collegiate [Church] for the first year. We went to community centers and schools, then had a First Street storefront for years. We built the building [at 402 E. Eighth St.] on Avenue D in 2010 in a vacant lot and opened in 2013.”

Pentecost retired in 2020 and, in collaboration with Flores, is now curator of Foto Espacio. There will be a rotating series of photography, film and design exhibitions, with an effort to build relationships with national and international photographers. The inaugural photography exhibit, which opened June 1 and runs through Sept. 1, “Visions of Loisaida,” showcases the work of four legendary Loisaida documentary photographers.

On Tues., June 21, for the first in this summer’s “Music is Our Muse” performance, talk and film series, La Sala will present live music by local percussionists from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m., followed by a screening of “Mambo City,” by Bette Wanderman, a rarely seen portrait of the Latin Music/Salsa Dance Party that ran for more than a decade at The Parkside Lounge on E. Houston Street.

At a date still to be determined, the award-winning 1991 film “Rock Soup,” directed by Lech Kowalksi, featuring Kalif Beacon, a homeless man who feeds other homeless people, will be screened at La Sala de Pepe. It was shot at CHARAS/El Bohio.

Be First to Comment