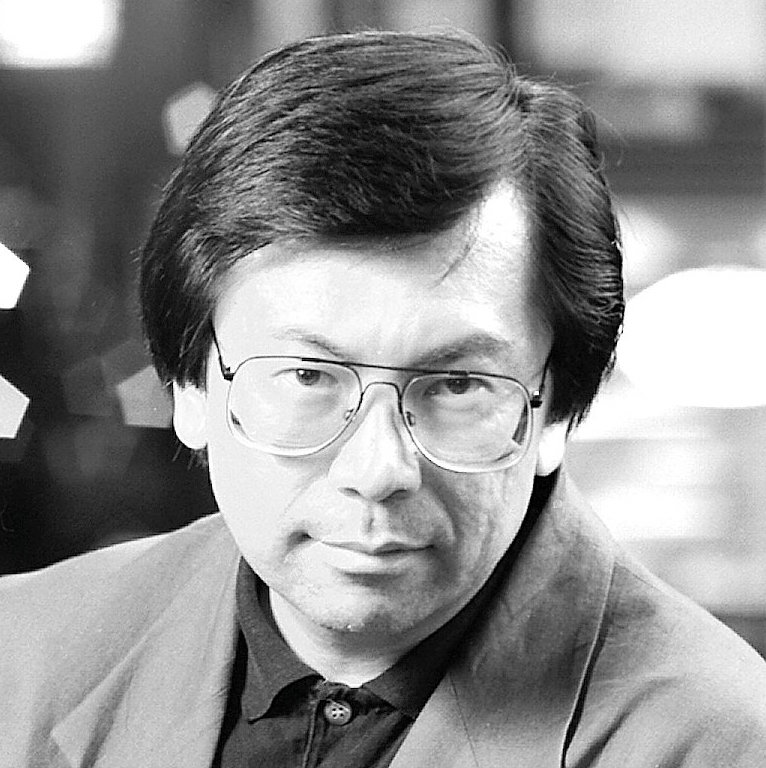

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Corky Lee’s memorial on Zoom last Friday night was massive. The numbers fluctuated up and down during the two-hour-long event. But at one point at the beginning there were 420 people — 20 people per screen spread over a total of 21 screens.

During the memorial, speakers proposed that, in Lee’s honor, a statue of him be erected in Chinatown’s Kimlau Square and that Mosco St. be renamed “Corky Lee Way.”

People from around the country and around the globe, as far away as Indonesia, were logged on. They came to share and hear memories and thoughts about the trailblazing activist photographer, 73, who died Jan. 27 of COVID.

The memorial was hosted by La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, where Lee had exhibited his photos.

For more than 50 years, Corky Lee tirelessly documented not only Manhattan’s Chinatown but also the larger Asian/Pacific American community around the city, as well as nationally.

“His work was about bringing Asian Americans into the mainstream consciousness,” said Karen Zhou, his longtime partner. “So we lost our community hero and friend.

“This is very hard,” she said, before choking up with emotion and being unable to continue.

Also giving remarks was state Senator John Liu. As former comptroller, he is the highest-ranking Asian elected to citywide office in New York City.

“I don’t remember a time when there hasn’t been Corky Lee around,” Liu said. “Quite honestly, he chronicled the APA community when no one else did.

“Certainly, the mainstream media and the media community didn’t care what was happening in the APA community. If not for Corky Lee, much of our history would not have been chronicled.

“He never took himself too seriously, as serious as the work he was doing,” Liu added. “Corky, you’re badly missed, man. You went too soon. But take comfort that you and the work you’ve done will be part of our community forever.”

Nydia Velazquez was on a plane leaving from Washington, D.C. But Lingxia Ye, her Lower East Side community liaison, shared the congressmember’s thoughts about Lee in the Zoom memorial’s chat section.

“She has been very shaken by his passing,” she wrote. “His passing is a great loss, but his memory lives on.”

Congressmember Grace Meng said, “Corky was an institution, a wonderful photographer who for decades captured the achievements and struggles of Asian Americans.

“Corky was like a walking museum. He took important and memorable photos with his camera to document the Asian American community across the country. The impact that Corky Lee has had, his legacy will truly live on.”

In a particularly moving moment, Perry Yung played the shakuhachi flute for a several minutes, after having first asked everyone to write one word each in the chat, describing their feelings about Lee.

Here are some of the words they typed as Yung played peaceful notes on his flute in memory of Lee:

shoot [as in take a photo]… connection… hope… kind… nurturing… humble… determined… legend… courage… enduring… steadiness… Corkyness!!… chi… equality… hope… infinity… perseverance… vision… funny… champion… compassion… wisdom… heart… sympathy… warrior… real… legacy… community… heritage… genius.. soul-brother… honesty… empowering… truth… visionary… focused… stories… imagine… solidarity… justice… generous… witness…

Yung recalled that Lee relished explaining the background behind each of his images.

“He loved telling the stories of those photos in person,” he said. “I will mostly miss his voice, telling his stories of those photos and how they came to be.”

Lee’s most famous photo is one that highlighted a story that had previously been “hidden.” In 2014, he recreated the “golden spike” event that celebrated the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, at Promontory Summit, in the Utah Territory, in 1869. However, Lee’s updated version, taken on the original photo’s 145th anniversary, included descendants of the Chinese laborers who had worked on the railroad.

Marilyn Abalos, a member of the Asian American Journalists Association, recalled how Lee had seen the original photo as a junior high school student — and had then bought a magnifying glass to try to find any Asian faces in the sea of workers. He couldn’t. Yet there had been at least 12,000 Chinese men who had labored on the railroad. Lee then went about personally organizing the photo shoot with the descendants.

“He hoped for 145 people — got 200,” she said.

In a video of the 2014 event, one of the descendants is told by park officials to get off of one of the trains. But the man refuses, saying he has a right to stand there.

After taking the photo, Lee exhorts the crowd from atop his ladder, “We are not visitors! We are Chinese Americans, Asian Pacific Americans. … Keep saying…that we framed American history!”

Friend Steven DeCastro noted how, whenever he and Lee spoke on the phone, Lee would never be the one to hang up.

“Even when he was in the hospital [with COVID],” he said, with smile. “He was still alert and planning for the future. He was someone who was always on the move.”

That drive led Lee to achieve greatness, he said, “so much so that he’s not just a prominent Asian American, he’s a prominent American.”

Lee worked full time at a printing business, somehow working his documentary photography in on the side. Sinaj Huda, a co-worker at Expedi printing from 1989 to 1993, said Lee was always welcoming.

“He never made anyone feel lesser than who they are,” he said. “Always calm. Never seen him lose his temper. I’m a Sikh American. His pictures of the Sikh Day Parade are very amazing.”

Karen Lee, a childhood friend, noted that, like her, Corky Lee had grown up a “laundry kid.” Lee’s father was a laundryman and his mother a seamstress.

She also shared a little-known fact about Corky Lee, that he was a writer, too. Lee penned a comedic play called “Chinese Men Can’t Make Me Laugh.” TV newscaster Connie Chung is a character in it.

“Corky questioned Connie’s tacit alignment with the white race,” she noted. “He also questioned stereotypes about Asian men as only hard workers without senses of humor.”

Tina Mak, Lee’s grandniece, also spoke. She said she sometimes recognized his qualities in her, including his sense of humor.

Victor Huey recalled how, after Lee’s wife died in 2001, Lee “went into a dark place.” However, after meeting Karen Zhou, the photographer became more public than he had ever been before.

“The more time went on,” he said, “the more energy he had, till the last decade he was super-Corky.”

Similarly, Geoff Lee said, “Karen really allowed him to be Corky.”

Luis Francia, a Filipino American and fellow photographer, shared how he would unfailingly bump into Lee wherever he went.

“He was everywhere, at every event,” he said, quipping, “Corky, if you can hear us, send us the shots!”

Lee was also remembered for the way he connected people. Ben Chan related how crossing paths with the activist lensman had changed his life.

“I met Corky at a protest when I was a college student,” he wrote in the chat. “He took my photo because he liked my ‘I Am Not the Chinese Food Delivery Boy’ T-shirt. A couple of weeks after meeting him, he reached out to me and told me to crash a lawyer diner he was photographing at the Waldorf-Astoria. At that event, Corky introduced me to the person I ended up donating one of my kidneys to seven years later.”

A friend now living in Hong Kong proposed an annual day where, in a lighthearted tribute to the photographer, people would wear a Corky Lee wig and eyeglasses, mimicking the unchanging hairstyle and look he sported through the decades.

On a more serious note, Ava Chin proposed in the chat that Mosco St. in Chinatown be named “Corky Lee Way.” There was also support for creating a scholarship in Corky Lee’s name for APA students at the City University of New York.

Others urged that a statue of Lee — holding his ever-present camera — be erected in Kimlau Square.

Indeed, someone said that, among the pantheon of Asian American heroes, Corky Lee ranks right at the top — at least equal to if not greater than another famed Lee, Bruce Lee.

Be First to Comment