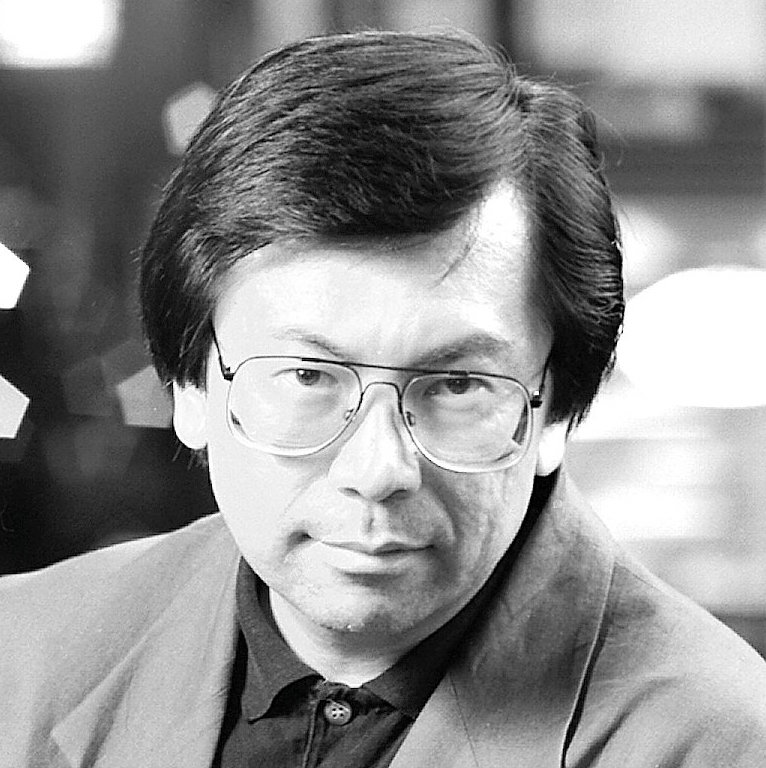

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Updated Jan. 28, 2:30 a.m.: Corky Lee, the preeminent Chinatown documentary photographer and activist, has lost his battle with COVID.

Lee, 73, died at 1 a.m. on Wednesday morning at L.I. Jewish Forest Hills/Northwell Health Hospital, according to his friend and fellow activist Karlin Chan.

As The Village Sun previously reported, Lee was admitted to the hospital on Jan. 7. He was in the intensive-care unit, then out of it, then moved back into it again. This past Saturday, he took a turn for the worse and had to be intubated, according to Chan.

His friends set up a Facebook page for him, the Corky Lee Recovery Fundraiser, that raised nearly $46,000 to help pay for his medical bills associated with his hospitalization.

On Jan. 16, Shirley Ng posted on the fundraiser page that Lee was “stable and drinking apple juice to keep his throat from getting dry. He is in good spirits. He is still in hospital and needs to get his oxygen level up.”

Just a week before he died, there was still hope that Lee would pull through. Ng posted that the photographer had given his brother, John, “a thumbs up” on Jan. 19, leading them to guess he was “still stable.”

Two days before Lee’s death, Wilma Consul posted on the fundraiser page: “We just had a prayer circle for him. 272 to 274 people attended. Corky needs our prayers right now. I hope he heard us, and that we were so loud, he’ll wanna wake up and take all our pictures.”

Karen Zhou, Lee’s longtime partner, said, “there had been roller coaster days with ups and downs” as the photographer’s health status fluctuated wildly as he battled the virus.

“Corky had suffered a lot while hospitalized,” she wrote, “and I pray that where he is in heaven, he is free of pain and suffering and full of happiness, love and peace.

“My heart breaks that Corky is gone,” Zhou said. “He had a lot of life in him, always running around photographing the Asian American community that he loved. His life’s passion and work over the last four decades is about getting Asian Americans in the picture and of righting wrongs and combating indifference, injustice and stereotypes through his photos.”

It was not immediately clear how Lee may have contracted COVID. He had held a photo exhibit in a newsstand in Chinatown, but that was in October, well before he would have become infected. The newsstand’s owner let Lee and the community use it temporarily for the exhibit.

“He was very careful with masking and social distancing. He was hyper-aware about safety,” a longtime friend said, requesting anonymity. “The newsstand exhibit was organized to be open-air and COVID-safe and he maintained social distance, mask protocols, etc.”

The friend said that, a few months ago, Lee expressed concern that he had walked past a public school near his home when school let out and students were not social distancing. He was afraid he might have been exposed that day — but, again, it was back in September or October.

Yet, Lee continued to ride the subway and dine out within mandated guidelines, exercising reasonable caution, all the while continuing his documentary photography work.

A gentle soul with a wry sense of humor, Lee went by the whimsical moniker the “undisputed unofficial Asian American photographer laureate.” For nearly 50 years, starting in the 1970s, he documented Manhattan’s Chinatown and the city’s Asian-American and Pacific Islander communities.

The slogan on his Facebook page is “An ABC from NYC…wielding a camera to slay injustices against APA’s.” (ABC stands for “American-born Chinese” and APA for “Asian Pacific Americans.”)

Lee covered everything from the Chinatown protests over the beating of Peter Yew by Fifth Precinct police in 1975 to the survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bombing and the fight for Chinatown World War II veterans to be honored for their valor.

“He was a staple in the Asian community documenting Asian struggles for visibility and equality,” Chan said. “He traveled the country to document rallies, protests and even organized a few these last few years.”

State Senator John Liu, New York City’s former comptroller, said the importance of Lee’s role in highlighting Asian-American history could not be overestimated.

Corky Lee is synonymous with Asian American history in New York and beyond. Indeed, without his efforts, much of our history may have gone unnoticed and unchronicled. 1/3 https://t.co/YLox58mCaJ

— John C. Liu (@LiuNewYork) January 28, 2021

Christopher Marte, a candidate for City Council in Lower Manhattan’s District 1, tweeted that Lee was “a pillar of Chinatown activism.”

Corky was a fighter, an artist, and a pillar of Chinatown activism. His passing is an unimaginable loss to our entire community, and to the Asian-American diaspora across the country. His dedication to justice lives on in all who had the opportunity to learn from him.#restinpower pic.twitter.com/upAYypOydQ

— Christopher Marte (@ChrisMarteNYC) January 27, 2021

Posting on Lee’s personal Facebook page after his death, Jason Ma, a member of one group that the photographer documented, recalled Lee’s kindness:

“Dear Corky, I remember at my first Chinese Railroad Workers Descendants Association conference, when I didn’t know anyone, you took me around and introduced me to people. Thanks so much for that kindness. We’ll all miss you terribly.”

Corky Lee was the eldest son and second child born to Chinese immigrants Lee Yin Chuck and Jung See Lee.

According to p.s. alumni, an online network for city public school graduates, which highlighted Lee as an Alumni Champion, he attended Jamaica High School and Queens College. Lee’s bio states that, starting out, he had to borrow cameras because he spent all his money going on dates. According to the site, Mayor David Dinkins proclaimed May 5, 1988, “Corky Lee Day” in New York City.

“Corky studied American history at Queens College,” the bio notes. “[In junior high school] he saw a photo in an American history textbook that depicted workers on the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah — a group that, in real life, was almost entirely made up of Chinese workers — and included not a single Chinese person in the picture. He saw this as an erasure of history: ‘History — at least photographically — says that the Chinese were not present,’ Corky says.

“In response to that misrepresentative photo, Corky staged a retake of the famous shot by gathering some of the descendants of the Chinese railroad workers in the same spot as the original photo.

“Throughout his life, Corky noticed that Asian history was repeatedly left out of conversations, prompting him to make a change through focusing his photographic work on making his culture more visible in the media both through political and everyday photos.”

In the 1990s and 2000s, Corky Lee frequently contributed his photos to Downtown Express and The Villager, two local Manhattan weekly newspapers. He mainly covered Asian American-related events, though also shot spot news.

In addition to his photography, Lee worked at Expedi Printing, which prints New York City-area community newspapers, among other publications. The company used to be based in the Meatpacking District before relocating to the boroughs as the area upscaled.

On a personal level, Lee suffered a devastating blow when his beloved wife died from cancer about 20 years ago.

He is survived by his partner, Karen Zhou, his brother, John Lee, of Carlsbad, California, his sister-in-law and two nieces, and the children of his his older sister, Ellen, who predeceased him.

A private service will be held at Wah Wing Sang Funeral Home, at 26 Mulberry St., in the coming days. In lieu of flowers, donations in Corky Lee’s memory can be made to the Asian American Journalist Association (AAJA) Photog Affinity Group, www.aaja.org.

Chan said there will probably be other memorials held in different cities across the country, in small groups due to COVID.

“Undoubtedly, the American Legion Kimlau Post [in Chinatown] will hold some kind of memorial because he was past commander of the Sons of American Legion there,” Chan noted.

Although Lee was not a veteran, his father served in World War II.

Corky Lee strongly advocated for the Chinese American WWII Veterans Congressional Gold Medal Act. Made law in 2018, the act collectively awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the roughly 20,000 Chinese-American veterans of WW II, in recognition of their dedicated service. About 300 of the vets survive today. The medals were awarded Dec. 9 in a virtual ceremony.

Corrections: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that, a couple of weeks before he was admitted to the hospital for COVID, Corky Lee had held an outdoor exhibit in a newsstand in Chinatown. However, in fact, Lee held that exhibit from Oct. 16 to Oct. 25, more than two months before he became ill. Also, an earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Lee died at Flushing Hospital, when it was actually L.I. Jewish Forest Hills/Northwell Health Hospital.

I had the great pleasure of working with Corky Lee at The Villager and Downtown Express for many years. He was such a nice man, a great talent in his profession and a leading contributor to the community. Through his lens, we saw it all by his giving us a front-row seat.

[…] Corky Lee, a photographer and activist who documented New York’s Chinatown, has died of COVID-19 at age 73. (The Village […]

[…] RIP: Corky Lee, documentarian of Chinatown. […]

Yes, in terms of an NYC community documentary photographer, Corky Lee was one of The Big Ones. His dedication and passion was documenting the various sides of NYC Chinatown. Capturing NYC Chinatown, Corky was The Man. I hope that his archives end up in a place that will be reachable for anyone with a thirst to learn what NYC Chinatown looked like during his years of documenting it. From all sides. I am sad that The Villager Newspaper disappeared. That was one of the last of the newspapers that published Downtown documentary photographers. Two sad recent deaths: Corky Lee and The Villager Newspaper.

sad day…..a great loss to all

[…] (The Village Sun Obit) […]