BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | The C.O.O. of a financial firm that lost hundreds of workers — and his own brother — on 9/11, family members of victims, volunteers who pitched in at Ground Zero, everyday New Yorkers and tourists. All of them converged at the 9/11 Memorial on Saturday to mark the 20th anniversary of the worst terrorist attack in both American and world history.

Like that fateful day two decades ago, the weather was beautiful. Notably, though, there were a lot more people who visited the memorial this anniversary than usual, given its significance as the 20th.

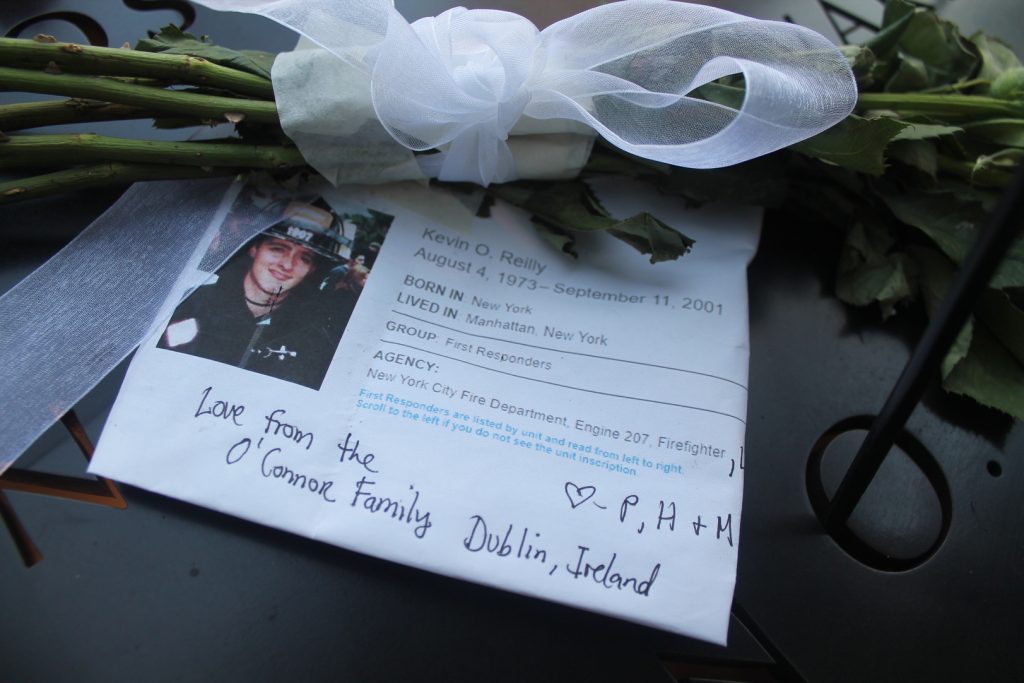

The morning had seen the traditional remembrance ceremony, with moments of silence marking when the two jets hit the Twin Towers, plus the solemn reading aloud of the names of the nearly 3,000 victims. Among the dignitaries in attendance were President Biden and former Presidents Obama and Clinton.

Later in the afternoon, the 9/11 Memorial site was packed with visitors. Some stood reverently around the two black pools with waterfalls where the Trade Center towers once soared. Many, of course, were snapping photos and taking videos on their phones of the scene and of the soaring One World Trade Center.

A lot of people just strolled through the sun-dappled plaza dotted with small trees, pausing here and there to take in the scene. The waterfalls provided a soothing white noise, enveloping the space in a peaceful bubble.

Beyond those coming to grieve or simply visit, there were small pockets of activity. A Marine jauntily posed for photos with all takers. A guy with a large, colorful parrot drew a small crowd.

Over on Fulton Street a man held a sign proclaiming, “Jesus Christ is a 9/11 Survivor.” Nearby, the conspiracy theorists had staked out their usual spot, their placards on the pavement charging that 7 World Trace Center was brought down by “controlled demolition.”

The C.O.O.

A gallant-looking group of men in black suits were handing out white roses to people. Asked who they were, one of them, a young man, said they were with Cantor Fitzgerald, the financial-services firm that was devastated in the 9/11 attack. He said, for more information, to talk to a man with a beard. It was his father, Howard Lutnick, the firm’s chief operating officer.

Lutnick said that it was, in fact, that same young man, his son Kyle, whom he had been dropping off at his first day of kindergarten on the morning of 9/11, which was why Lutnick was not in 1 World Trade Center when the plane hit. All 658 of the firm’s employees in the building that day were killed, including his brother, Gary.

Also among those who perished was Douglas Gardner, Cantor’s executive managing director and Lutnick’s best friend from college. This writer, when he was just starting out as a reporter at the summer weekly Fire Island News, used to play with Gardner in the Fire Island Basketball Tournament; he had been thinking about him on this anniversary. Gary Lutnick’s and Gardner’s names are carved next to each other on the 9/11 Memorial, on the southeastern corner of the northern tower’s footprint.

Asked his thoughts on the tragedy’s 20th anniversary, Lutnick didn’t delve into painful emotions. He reflected on the passage of time. He put a positive spin on things, saying how the company had managed to grow despite the unimaginable loss.

“I worked at the company for 18 years before 9/11,” he said. “Now it’s been 20 years since — it’s a long time. We had 960 employees [on 9/11]. We lost 658. Now we have 5,000.”

Following the Trade Center’s destruction, Lutnick created the Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund, which has given out more than $280 million to aid families of Cantor employees who were lost in the attack, as well as to victims of natural disasters.

With a gracious smile, he continued on his way, greeting people at the memorial, handing out white roses.

The family member

Madeline Luna, 34, had just finished huddling with family and friends at a spot along the south side of the northern pool. They had been doing a group prayer, she explained.

Her uncle, who was a baker at the World Trade Center, was supposed to have the day off on 9/11 but was called in to work. Meanwhile, her aunt was interviewing for a job somewhere in the towers that day. Neither made it out alive. Luna was in her early teens then.

She said they had not been to the memorial event for the past seven years, but felt compelled to come on the 20th anniversary. Asked if the date gets any easier as the years slide by, she said, yes, slightly.

“It actually gets a bit easier,” she said, “but there’s always going to be a tragedy in our head.”

The volunteers

Two big guys with bikes were standing on the south side of the pool where the 2 W.T.C. tower used to be. One of them had a white scarf draped around his neck and was dressed all in white, though he wasn’t a cleric. The scarf was from a Sikh temple in Queens they both like to attend from time to time.

On 9/11, the friends were both living in the East Village and were musicians in bands. After the attack, they joined the effort at The Pile, as it was called.

“We were the outlaw volunteers,” Russell Hawkey, the man in white, said.

He had worked on the “massage boat,” helping the hard hats and other workers de-stress. He had biked down from the East Village balancing a massage table on his head with one arm, then got set up on a Circle Line-type boat that had docked near Ground Zero. Eventually, it became a bigger operation, with more than a dozen masseuses and the Red Cross in charge. But he said he was the first.

Hawkey’s other valuable role was to break into places at the blasted-out Trade Center site and grab edible food for the first responders.

“The police didn’t want to do it, there was a chain of command,” he explained. “So they asked us to do it. I broke into Starbucks with a big sledgehammer and took all the cakes and sandwiches.”

His friend Tiger Koehn, for his part, volunteered at the nearby Embassy Suites Hotel cooking food for the Ground Zero workers.

“We also made fake O.E.M. badges,” Koehn recalled, referring to the city’s Office of Emergency Management. “It was one badge, red, with the same number. They were all the same. They weren’t checking them very closely.”

“I made ’em at Kinko’s on Astor Place,” his friend chimed in.

They had started out on the bucket brigade on The Pile, clearing the debris away, one bucket at a time, passing them along a chain of hands from one worker to the next. In the first days, some still held out hope of finding someone alive in the rubble, before it turned from a rescue to a recovery effort.

“The lime in the cement was burning,” Koehn recalled of working on the bucket brigade. “It was so hot, it was melting our boots in a few hours.”

Koehn is well known in the gothic rock scene. He’s the drummer for the New Creatures and used to sometimes hit the skins with 3 Teens Kill 4. He said he hadn’t been back to the 9/11 Memorial for some time because he gets too emotional, becomes teary-eyed. But Hawkey had been watching coverage of the 9/11 anniversary on TV and told him they should go.

“The first time I’ve been back in years,” Koehn said.

His girlfriend was a bartender at Windows on the World, the restaurant atop the north tower. They had eaten there just three weeks earlier. She was supposed to work the morning shift that day.

“All her friends, dead…” he said. “She was late.”

Koehn also was pals with Firefighter Patty Fitzpatrick, a member of the firehouse at Sixth Ave. and Houston St., which suffered staggering losses on 9/11. He didn’t make it back.

“He was one of the first ones in,” the drummer said.

Both men said it was weird experiencing the memorial with so many tourists crawling all over the place but they shrugged it off.

The people

Michelle, a tall woman from East Harlem, expressed a common thought — that she remembered exactly what she was doing during the 9/11 attack.

“This is something that will be embedded in our brains forever,” she said. “I was in Midtown. I remember everything from that day going forward.”

Indeed, like another generation’s touchstone moment, “Where were you when J.F.K. was shot?” it’s now “Where were you on 9/11?”

Hyunbin Shin, 23, was 4 years old in Korea when the terrorists targeted Lower Manhattan. Now studying in New York City, she said it was the first time she had visited the memorial.

“Every anniversary is special,” she said, “but especially the 20th.”

Will, originally from Connecticut, now Brooklyn, remarked on the tranquility of the memorial site on the anniversary despite all the people milling about.

“Peaceful,” he said, when asked for his thoughts. “It’s slower-paced than I expected. Reflects well on the city.”

Yes, ironically — intentionally — in a place once the scene of such unearthly violence birthed by fanatical hatred, there was a feeling of serenity and safety and of remembrance. The 9/11 Memorial has done its job.

Twilight bagpipes

As evening fell, the skirl of “Amazing Grace” on a bagpipe came from the intersection outside the southeast corner of the 9/11 Memorial. Firefighters were holding a gathering there, with music, speeches. Soon, it seemed, everyone who had been around the two square pools had converged at this spot. Many hands held up cell phones, that ubiquitous symbol of our age, to capture the moment.

Clearly, people were looking for some sort of more organized event to join in on. The firefighters’ gathering was better and more communal than taking a photo with a Marine — or a parrot.

As the darkness deepened, the twin white beams of the Tribute in Light could be seen beaming up to the heavens from somewhere just south of the World Trade Center.

Donald Trump passed up the morning’s memorial ceremony but had said he would visit the World Trade Center later in the day. In the end, he never showed up, though. Instead he gave a pep talk to police officers at the 17th Precinct on E. 51st St.

“Trump’s already gone, out of New York,” a cop in a squad car by the memorial said. “He’s commentating on a fight in Florida tonight. I’m not kidding.”

Beautiful and powerful tribute to the thousands lost and the survivors of 9/11 20 years ago.