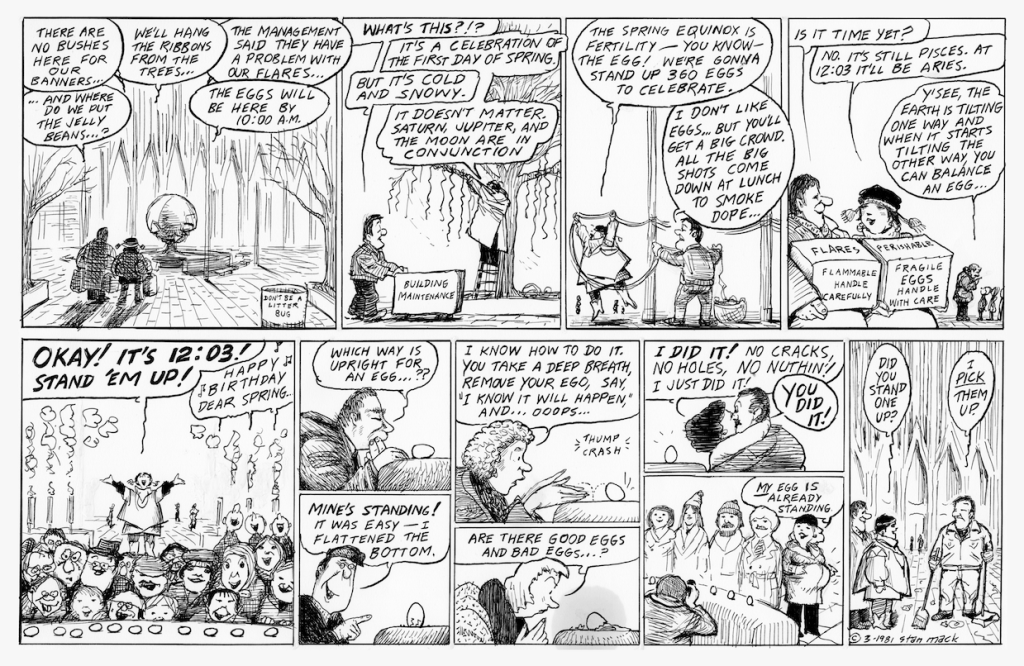

BY THE VILLAGE SUN | Real Life Funnies, a strip by cartoonist Stan Mack, was a standing feature every week in The Village Voice from 1974 to 1995. Toting a sketchbook and pencils in a pouch on his belt, Mack — a pioneer of documentary cartooning — scoured New York City’s streets looking — and listening — for stories. Other times, he would set things up in advance to cover events like a gathering of UFO devotees or other offbeat happenings. His cartoons always used verbatim dialogue, hence, the moniker Real Life Funnies.

On June 11, Fanagraphics Underground published a new, 336-page, hardcover book, “a foreword by CNN anchor Jake Tapper and an afterword by Jeannette Walls, author of the memoir “The Glass Castle.”

In a review, Jeremiah Moss of the “Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York” blog, wrote, “Thank goodness we have Stan Mack’s Real Life Funnies to remind us that New York was once a wild, weird, creative place filled with people who always had something interesting to say. And thank goodness Stan Mack was around to hear them say it.”

Following below is an interview with Stan Mack.

* * *

VILLAGE SUN: What were some of your favorite Real Life Funnies that you penned about things in Greenwich Village/East Village/Downtown area? And what did you like about doing them?

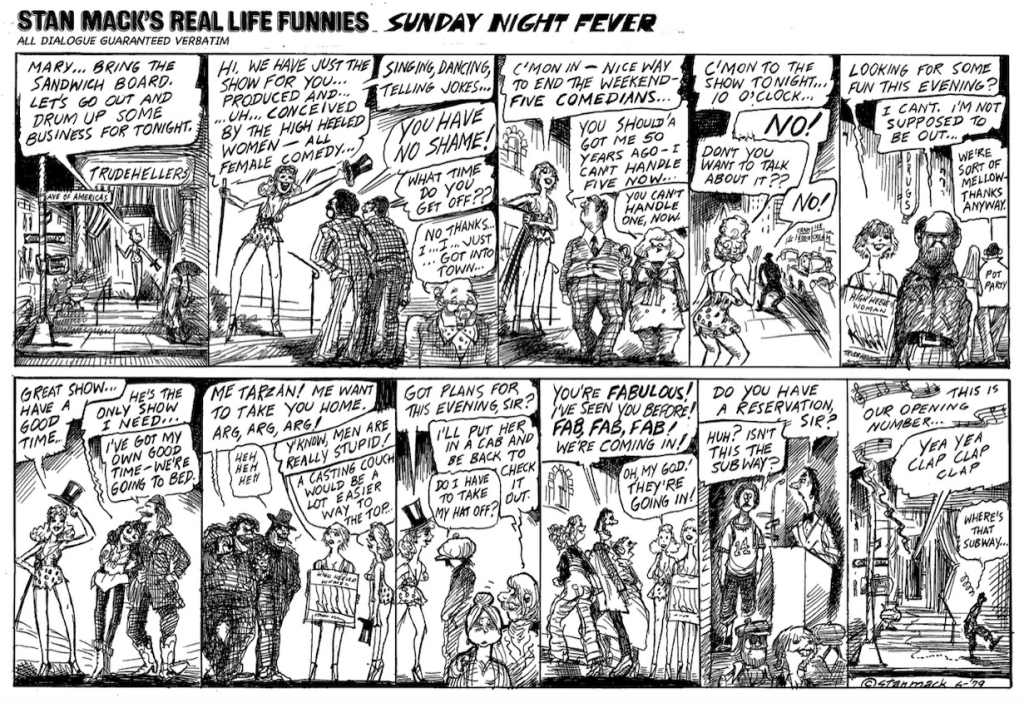

STAN MACK: Whether simply wandering or going to specific events, I was often in the Village. For example, one Sunday night in the late ’70s, I walked over to Trude Heller’s, which was gone by the ’80s but had been an “in” nightclub on Sixth Avenue at Ninth Street. The High Heeled Women, a funny, sexy, song-and-dance act, hot in the Downtown cafe scene, were performing at the club. To drum up business they were out front, dressed in skimpy outfits, encouraging passersby to come to the show. I hung out, sketched people, listened to the comic banter. Classic Village attitude and great fun for me.

The feminist and sexual revolutions were everywhere in the ’70s — like at the Erotic Baker on Christopher Street. As the name suggests, all their baked goods were sex-related, in a comic way. With the permission of the owners I hung out at the popular bakery, where business was brisk.

Were you living Downtown when you were doing these articles for the Voice? What are some of your best — or at least most memorable — memories about the neighborhood?

For much of the strip’s 20-year run, I first lived on 12th Street between Fifth and Sixth, next to The New School, and then Greenwich Street between West 10th and Charles. During those years, the Voice was in three different locations, all in the Village.

On the Voice’s deadline night, I’d race my strip, hot off the drawing board, across town to wherever the Voice offices were at the time — University Place at 11th Street, Broadway at 13th or Cooper Square — like I was delivering a sizzling pizza.

What are your memories of working at the Voice? Were you in the office there much?

My drawing board was in my apartment. But I wandered the Voice offices a lot. Before the Voice, I was an art director at the New York Herald Tribune and then The New York Times. The tumult of the Voice’s offices felt like home. And sometimes the Voice editors and writers themselves became subjects in my strip. For the most part they were good-natured about it. In one story, in which I covered the closing night of a Voice redesign, the editor asked if I would include her dog.

What do you think about how the Voice ultimately wound up?

The Voice jettisoned Real Life Funnies in 1995. After that I was an outsider, and I didn’t have any real information about what was going on inside the city room or the offices of power. But at this point the Voice looks to be a stump of what was once a very healthy tree.

Your work has some similarities, it seems, to that of R. Crumb. What do you think of his work and how do you compare yours to his? Your drawing style seems somehow a bit reminiscent — and yet R. Crumb’s cartoons are obviously often about wild “flights of fancy,” as in, “loosely based in or on reality.” Whereas your comics are “Real Life.”

R. Crumb is a brilliant artist. He was at the forefront of the huge underground comics movement of the ’60s. I think it’s fair to say his reference points were traditional comics, which he took to a very different place. Rather than “loosely based in reality,” Crumb was for many of that generation the reality. I did devour comics as a kid, but I think my Real Life Funnies had as much to do with newspaper columnists and reporters as with the comics.

What have you been doing since you stopped publishing your strip in the Voice? Do you still publish the Real Life Funnies — or other cartoons/illustrations?

Real Life Funnies may be one of the most important projects of my career, but I’ve done significant work as the art director of The New York Times Sunday Magazine, written and drawn a number of books for children, young adults and adults, including “Revolting Rebels,” a cartoon history of the American Revolution; “The Story of the Jews,” a cartoon history; and “Janet & Me,” an illustrated memoir about my time as caregiver for my partner, Janet Bode, who eventually died of breast cancer. That book is my most personal effort.

Were Real Life Funnies political — in terms of your own views or those of the individuals you portrayed? Or did you see your work as really more apolitical reportage?

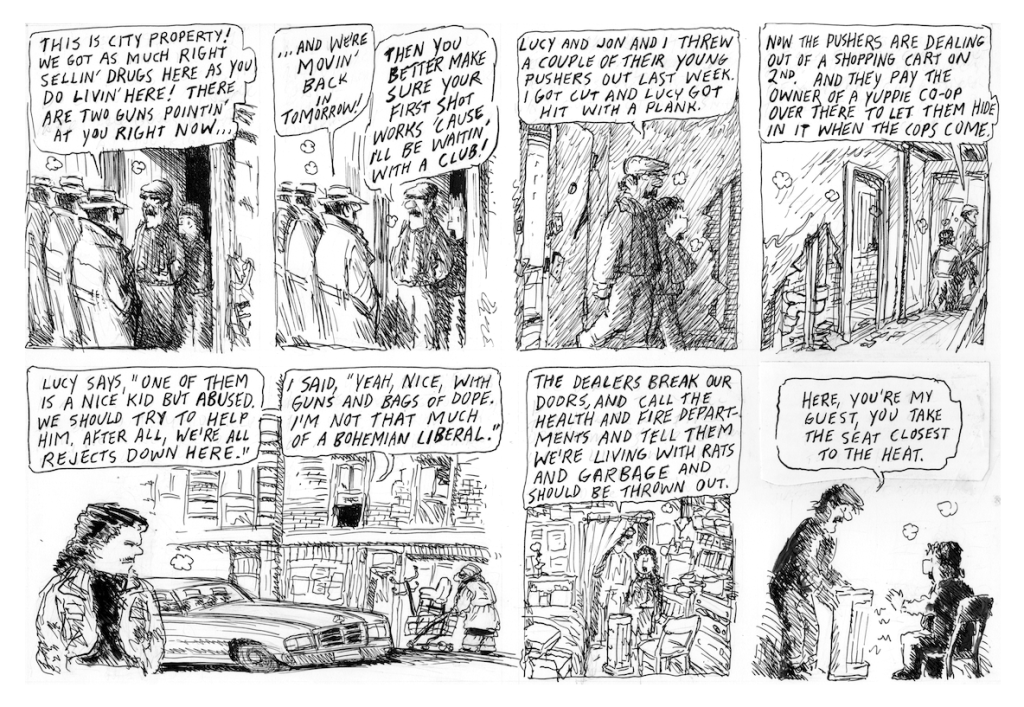

While my comics were rarely overtly political, they always seemed to favor the underdog over the “fat cat.” In the late ’80s, drawn to the squatter movement in the East Village, at a time when homelessness was rampant in the city, I did stories from the political and personal perspectives of: squatters, the homeless, the drug addled, the longtime political activists, and the self-proclaimed anarchists and revolutionaries as they battled the police in the cause of affordable housing. However, I never did miss an opportunity to make fun of the foibles of “the good guys.”

Did you ever have any negative experiences doing a strip? Did you tend to “clear” things with your subjects first before you covered them? Or would you just sort of stumble upon something, sidle in and sort of “eavesdrop” on things?

People usually liked making appearances in my comic strips. I might get a note saying, “That guy with a beard in the lower left-hand corner of the third panel in your strip this week was me! Would you please sign my copy of the Voice?”

If I quoted and sketched people in a way they couldn’t be identified, whether on a movie line, in a bar or at a gathering of believers in UFOs, I didn’t ask permission. If I thought the person was identifiable, I’d clear it with them first. There were occasional glitches in my approach. One year, Macy’s held public tryouts to be Christmas elves. I joined and went through a day of simple instruction — and did a comic strip about it. When the strip ran, Macy’s angrily complained to the Voice business department, which passed along the complaint to the editor, who called me into his office. But the Voice was always in some serious legal wrangle because of the political revelations of their investigative reporters. David, the then-editor, offered a smile and a gentle, “Be careful.”

Do you have any cartoonists that you follow today? Are there classic cartoonists that you admire?

If I had to quickly pull three names out of my hat — and there are many more: the English artist George Cruikshank; the American sports cartoonist Willard Mullin; and the WWII battlefield artist Bill Mauldin. Totally different in style, each captured the essence of “real people.”

I don’t know most of the younger graphic novelists. I like to browse the bookstore shelves of current graphic novels, just to admire the skill and variety of those who have come of age combining words and pictures in both fiction and nonfiction. Very different from my days.

Have you ever thought of doing a graphic novel — and, if so, what would it be about?

In addition to the work I’ve already mentioned, I collaborated with my late partner, Janet Bode, on her books for young adults, which were hybrid combinations of text and comics. And my wife, Susan Champlin, and I have done two historical graphic novels for middle school kids. “The Pickpocket, the Spy, and the Lobsterbacks” takes place in the early days of the American Revolution, and “Our Fight, Our Time” is set in the South during the Civil War.

If you were a cartoonist starting out today, do you think you would be doing things the same way you did then? Would you somehow be using the Internet more or using CAD (computer-aided design), does that hold interest for you?

With the array of technologies available today, I’d still have to choose whichever tools — the most portable, unobtrusive and fast — would get me to the story. The problem is, those same technologies — the headsets, earbuds, smartphones and computers — which may increase communication within the Internet, would block my access to the real people in the real world. Very old-fashioned of me.

What do you think about how Downtown Manhattan has changed since when you were doing Real Life Funnies? What has changed? What has stayed the same?

Physically, New York is about change. Ditto the artists who have arrived here in recent times. I walk the streets of Downtown and spot a storefront that looks familiar — it was a magazine store run by my friend, a Chinese immigrant. He’s moved on and it’s now a Verizon store. And the people who go in and out of that store look different from the Villagers I remember. And what was once CBGB sells musical instruments.

NY’s local treasure…

Stan Mack is part of what makes New York City great!

Hi Mac, thanks and I think that you, too, in different way, embody the city in your powerful art.