BY ANDREW BERMAN | There’s a school of thought that the key to solving New York’s affordability crisis is to simply allow developers to build more housing. According to this theory, laws of supply and demand dictate that the problem is too little supply for too much demand, and so if we just increase supply, prices will come down across the board.

The de Blasio administration has been a major proponent of this approach, issuing a report earlier this year showing the city neighborhoods where housing supply increased most and least over the last 10 years, blaming the latter for the city’s affordability problems, and using it as a rationale for proposed upzonings.

Problem is, the reality in New York doesn’t line up very well with this very simple theory. And recently released data and studies directly contradict it.

Recently, StreetEasy released “The 10 Best NYC Neighborhoods for First-Time Buyers in 2021,” in which they looked for neighborhoods with “homes that would be affordable to New Yorkers ages 25 to 44 who earn the city’s median annual income.” They found 10 neighborhoods throughout the city that best fit the bill.

According to the supply/demand theory, these 10 neighborhoods should line up neatly with those with the most new housing produced, with the increased supply bringing prices down. But in fact, eight of the 10 best neighborhoods for affordable buys are in the bottom half of the city’s community districts for housing production; two of the 10 are actually at the very bottom of the city’s list for neighborhoods that have added new housing. By contrast, the five neighborhoods that topped the city’s list for most new additional housing units have all been noted for their sky-high and rising housing costs; none made the “Top 10” best buys list.

So does the basic law of supply and demand not apply in New York City? Of course it does. But the reality is, it’s only one of many factors that affect housing prices in our city and neighborhoods, and not all types of housing satisfy the same kind of demand. And so the trickle-down theory that says simply increasing production of new market-rate housing — typically at the highest end of the housing-price spectrum — not only may not help, but may hurt the cause of affordability.

The Soho/ Noho rezoning would nearly double the residential population of these tiny neighborhoods — and, over all, make their housing more expensive.

Soho and Noho, where the city is currently proposing a massive upzoning that it projects would nearly double the residential population of these tiny neighborhoods, is a perfect example. The city claims vastly increasing the supply of housing here would bring prices down and make these expensive neighborhoods, and New York, more affordable. Experience shows otherwise.

Average sale prices in these neighborhoods currently are indeed steep — $1.54 million according to city figures. This includes all housing sales in the neighborhood, most of which are lofts more than 100 years old, many sparklingly renovated but nevertheless in smaller buildings without doormen, amenities, views or standard layouts, and thus a lot of windowless interior space that requires a willingness to live unconventionally.

By contrast, units in new construction in these neighborhoods — the kind the city wants to allow thousands more of, in buildings with doormen and gyms and concierges and high floors with open views and conventional layouts and other amenities — go for an average of $6.437 million, or more than four times the average price for all new sales in the neighborhood. That’s no surprise given that the conventional amenities and goodies in these new units mean they appeal to a much broader range of buyers, with much more money, who likely would not consider living in a walk-up, or with windowless bedrooms, or having to open their own building’s front door or pick up their own packages, as much of the existing housing in the neighborhood requires.

This illustrates why simply allowing new market-rate construction in the neighborhood won’t bring prices down, but in fact will likely raise them. And that’s not just true for the tricked-out new buildings; older buildings on and near 57th Street have used their newfound proximity to the glossy high-rises of “Billionaires’ Row” as a major selling point. And the proliferation of amenity-packed high-rises along the Williamsburg, Greenpoint and Long Island City waterfronts has coincided with meteoric rises in housing prices in older housing stock in those neighborhoods, too.

If we really want to deal with our city’s affordability crisis, we need to quite simply create more affordable housing, and try to preserve as much of our existing affordable housing as possible, as more of it disappears each year. The de Blasio administration has, by contrast, relied upon a “trickle down” approach, where most new affordable housing is dependent upon private developers building high-priced market-rate developments, within which a much smaller number of “affordable” units are required as part of the deal. But the “affordable” units in these projects can actually require above-average incomes for New York City — and therefore are often not that “affordable.”

This has resulted in a glacial pace of progress, and a great deal of new expensive housing that actually may do as much or more to push up prices and push out lower-income residents as it does to help them. Worse, because the mayor combines these “affordable” housing requirements with upzonings that allow developers to build much larger buildings than current rules allow, it encourages the demolition and elimination of these neighborhoods’ existing rent-regulated affordable housing, which is overwhelmingly occupied by lower-income tenants who are then displaced.

Which isn’t to say that we shouldn’t allow or encourage new market-rate housing. But combining it with upzoning incentives to demolish existing affordable housing should never be part of the plan, and the many loopholes the mayor currently offers to developers allowing them to bypass affordable housing requirements should be eliminated. The affordable housing required as part of the deal should also be more broadly and deeply affordable — that is, include higher percentages for New Yorkers at lower incomes.

And there’s more we can do. A tremendous amount of office space lies empty in New York City, much of it in prime locations. We should incentivize converting it to housing, with requirements for real affordable housing as part of the deal.

Our single largest resource for affordable housing is the roughly 1 million remaining units of affordable rent-regulated housing in New York City. The rent reform laws of 2019 closed 25-year-old loopholes that allowed rent-regulated units to be deregulated, especially in higher-income neighborhoods where they were needed most. Now, virtually the only way to deregulate these units is to demolish them, which the city’s “affordable housing” upzonings encourage.

But in addition to avoiding upzonings that encourage demolition of affordable housing, the city and state could do more to ensure that rent-regulated affordable housing is available to those who really need it. Current state rules don’t attach income requirements to rent-regulated affordable housing. However, the city or state could offer incentives to landlords to rent these units to those whose incomes are no more than 30 percent of the annual rent — the target income-to-rent ratio for affordable housing. This would help ensure that when these units become vacant, instead of being destabilized as they often were before the 2019 rent law reforms, they would not only remain regulated and affordable, but house the lower- and moderate-income tenants who really need them.

At the very least, the city and state could set up a system for tracking these units when they become available, and connect them with tenants for whom the rent would be no more than 30 percent of their income — as opposed to higher-income tenants who don’t need these units as much.

A “let the market solve our problems” trickle-down approach not only won’t fix our affordability problems, it may well make them worse. A more thoughtful strategy that doesn’t simply seek to open the floodgates to market-rate development, but prioritizes preserving and creating truly affordable housing for those who need it, is the approach we need.

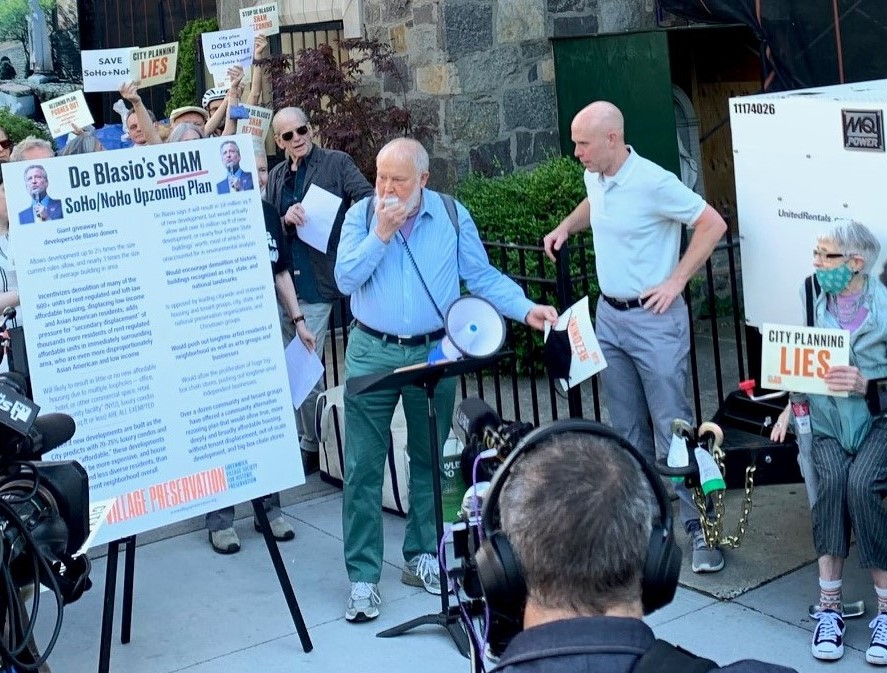

Berman is executive director, Village Preservation.

A very clear and well-put case on the trickle down supply-and-demand fallacy and the need for preservation of existing units and a more robust publicly owned housing approach. Applicable in cities across the country.

As a longtime renter in Manhattan and a freelance worker in the arts, I have watched the city I love be subjected to the whims of the mayor in office during various administrations (and his wealthy donors) in deciding the city’s future. Will we be an economically diverse melting pot of artists, immigrants, working-class residents and their families along with the wealthy or will we be a city of tall buildings that block out the sun and whose residents can actually afford what has become the definition of affordable? Will these buildings drive artists, lower-middle class and most service workers from our neighborhoods? How will the tourist trade change when the very unique heart of our city that draws millions to experience what they cannot find at home is demolished? What will our neighborhood communities look like when their communities are predominately homes or condos of the wealthy who see us as an investment without regard for our history? Change does not have to be defined by destruction.

please don’t pretend your interests here are about affordable housing

Don’t feed the troll.

This is the absolute stupidest drivel I have read in a long time (although not surprising given the source, I suppose). And disingenuous to boot! Really rich to say, “We need to quite simply create more affordable housing,” when you’re campaigning against the 100% affordable Haven Green project.

If anyone wants to read an actual expert on this, rather than this bozo citing random Trulia listings, check this out: https://research.upjohn.org/up_workingpapers/307/. To summarize: “new construction reduces demand and loosens the housing market in low- and middle-income areas, even in the short run.”

This is patently false — the Haven Green project lies outside of the bounds of our neighborhood, and thus we have never taken a position on it. Everything else in this comment is equally false.

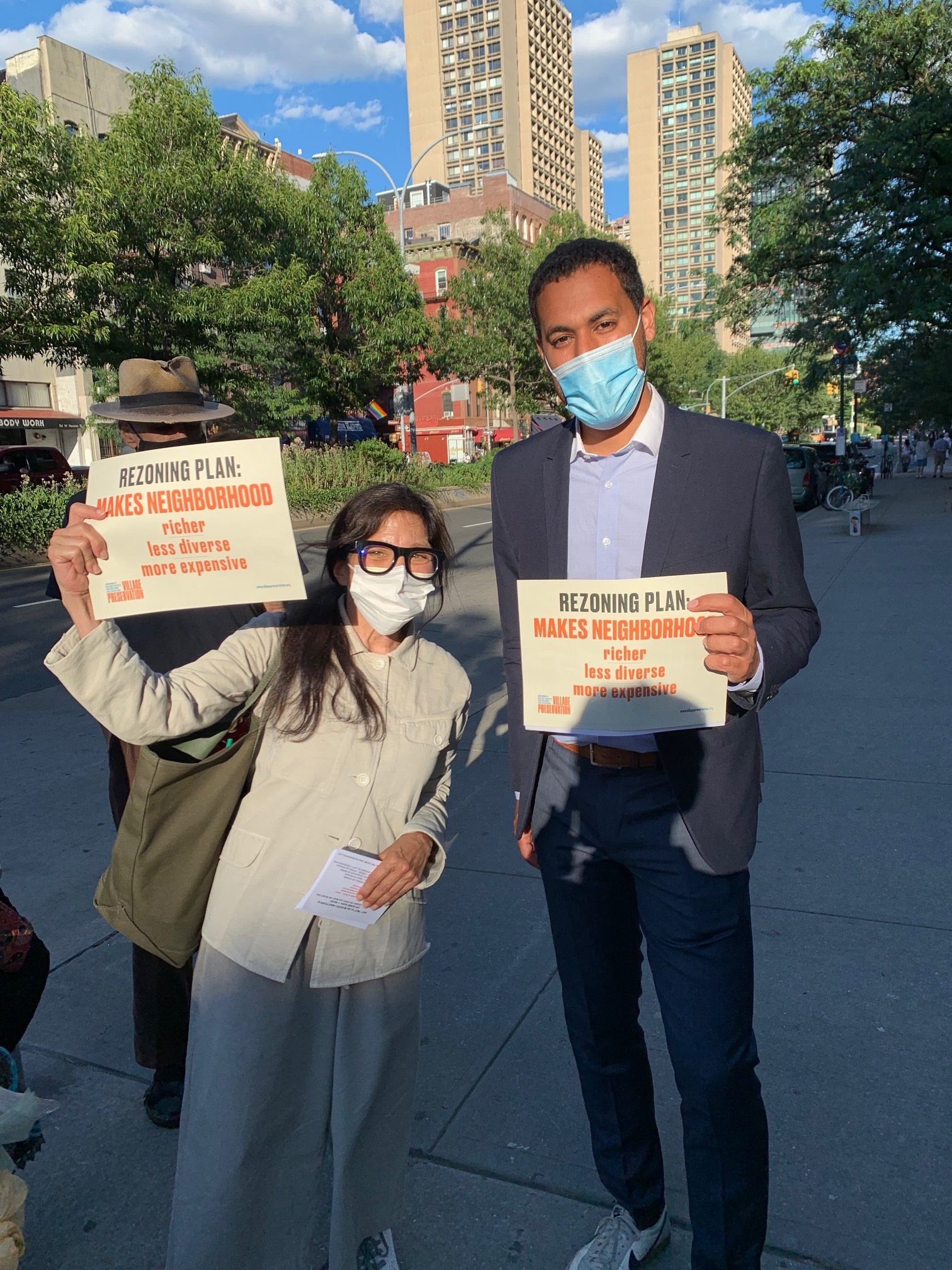

Hey, Andrew, thanks for engaging! So does that mean that you personally support Haven Green? Not asking you to speak for your org, but it’s an important question that goes to the intellectual honestly of your article here. Would really appreciate the clarification, because the cover photo on this post is Chris Marte, who admits he got into politics to sink that 100% affordable development. You and Chris are very publicly aligned on SoHo/NoHo. And your group is ideologically aligned with the various neighborhood groups and block associations that oppose Haven Green. But look, if you come out and say you support Haven Green, I will gladly admit that I am wrong.

Seriously, though, this whole post is either stupid or dishonest. You cited broker-babble on a random Trulia listing to try to show that Billionaires’ Row caused an increase in pricing of nearby housing. You use the fact that cheaper neighborhoods have cheaper housing to claim that supply and demand don’t apply. And you talk about the development and gentrification of Williamsburg without acknowledging that that happened in significant part because the East Village was downzoned at the same time (and because wealthy neighborhoods like yours don’t build enough housing to fit the wealthy people who want to live there, forcing them into the high-rises across the river). You either don’t understand the dynamics at play or you’re intentionally obfuscating them.

Anyway, here’s another study showing that market-rate housing helps low- and middle-income: https://ideas.repec.org/p/fer/wpaper/146.html. To summarize: “Market-rate supply is likely to improve affordability outside the sub-markets where new construction occurs and to benefit low-income people.”