BY PHYLLIS ECKHAUS | Today, what’s most striking about Astor Place is what’s not there. The plaza — a hangout for tourists and locals to sit, nosh and maybe take a selfie with “The Cube” — gives no hint of the culture war that seethed and erupted in that spot 175 years ago.

On May 7, 1849, a contingent of “Bowery b’hoys” in the cheap seats at the Astor Opera House pelted famous British tragedian William Charles Macready with produce and copper coins as he attempted to play Macbeth. The rowdies were fans of Edwin Forrest, Macready’s American-born thespian rival, who was himself performing Macbeth a few blocks away, and they were furiously resentful of Britain’s cultural hegemony and the New York elites that favored Macready.

“Down with the codfish aristocracy!” they yelled as Macready and cast fled the stage.

Theater riots were nothing new to 19th-century America. But this particular one spurred New York’s upper crust to action. Forty-seven of New York’s most notable — novelists Washington Irving and Herman Melville among them — petitioned Macready to return to the stage, promising that law and order would be maintained. Publishing their missive in the newspapers, they also enlisted the newly elected mayor to provide Macready with police protection against the projectile-throwing mob.

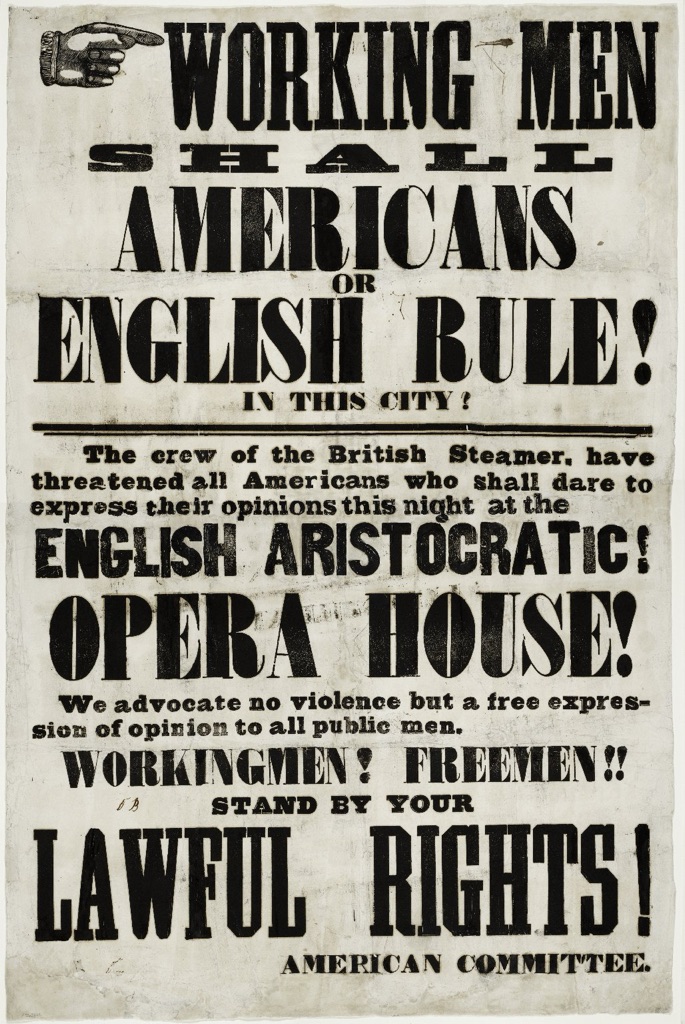

Tensions mounted. Some say Edwin Forrest himself surreptitiously provoked further hostilities. More conspicuous was the Tammany Hall operative Captain Isaiah Rynders, glad to make trouble for the new Whig mayor. Rynders printed and posted handbills stating, “SHALL AMERICANS OR ENGLISH RULE IN THIS CITY?” handed out free tickets to Macready’s May 10 performance, and plotted maximum disruption.

Rynders was assisted in this enterprise by the notorious “Ned Buntline,” the pseudonym of E.Z.C. Judson — Judson was the future founder of the nativist Know Nothing Party. He was also the sensationalist author who survived an attempted lynching to write at least 400 dime store novels, and to become the impresario who conceived of “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.”

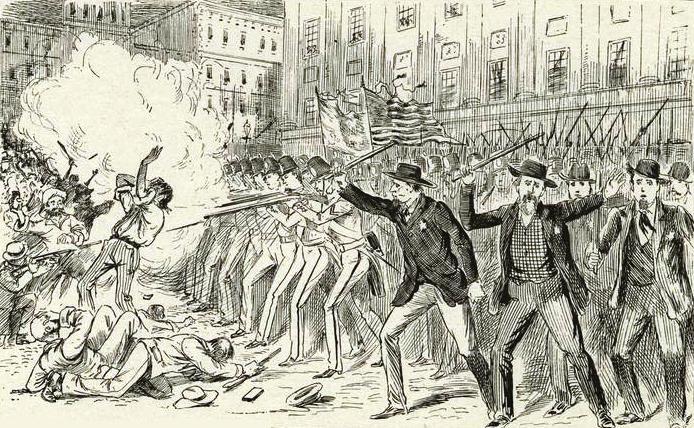

On May 10, the police chief informed the mayor — on just Day 2 of his administration — that the police force was not equipped to quell a major riot. The mayor called out the National Guard, the ultra-elite, “Silk Stocking” Seventh Regiment, which years later would privately fund the Park Avenue Armory.

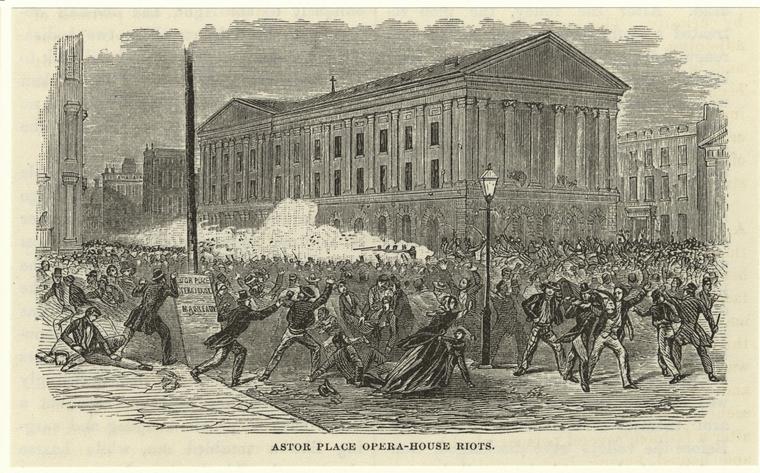

At that evening’s performance, as produce and invective flew, the police swarmed the audience, arresting protesters. A crowd of 10,000 massed outside the theater and broke in, hurling paving stones and crying, “Burn the damned den of aristocracy!”

Outmanned, the police called in the Seventh Regiment, which fired repeatedly into the crowd. Eighteen died that night; four others died within days. More than 150 were wounded or injured. The victims were mostly bystanders, none of them associated with Rynders. Of the dead, nearly a third were Irish laborers.

The next day, the city mustered a show of strength, putting more than 3,000 soldiers and deputized civilians on the streets. Rynders’s rally at City Hall Park demanded vengeance. But this time the thousands who again converged on Astor Place dispersed when the militia charged.

Rynders, defended by former President Martin Van Buren’s son, was acquitted of criminal charges. Judson was convicted, and celebrated as a hero upon his release.

So what do we make of these long-ago events? Do we marvel at the past popular fervor for the Bard of Avon? Can we compare the malcontents of May 10, 1849, with those who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2020? Or condemn the fatal deployment of the National Guard against innocent civilians?

Perhaps “all of the above.”

The Bowery b’hoys may have been uncouth rowdies but they took seriously the revolutionary promise of America — that “all men are created equal.” The Astor Place Riots exposed and bolstered the class system we’re not supposed to have — and showed just how profoundly pissed people get when they think they’ve been stiffed by the social contract. It’s a lesson that still has resonance.

The writer has gratefully drawn upon “Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898,” by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, for most of the facts in this piece.

I lived around the corner from Astor Place for 15 years and never knew this. How great to have unearthed and let us in on this piece of history! Thank you!

Amazing !

As a longtime East Village resident I never had a clue about this chapter of our history.

Thanks for the history lesson!

Thanks for crediting “Gotham.” For those unfamiliar with the book: 1,236 pages of text followed by 147 pages of References, a Bibliography, and 2 (!) indices — one for subjects and the second for names. This is a heavyweight book, but the writing is easily readable. And yes, many current events do — for better or worse — resemble history.

Anticipating a possible query, in addition to “b’hoys,” there were also “g’hals.”