BY ALISHA MEGHANI | If Atticus Finch had a doppelgänger in the 21st century, it would be Stephen Duncombe.

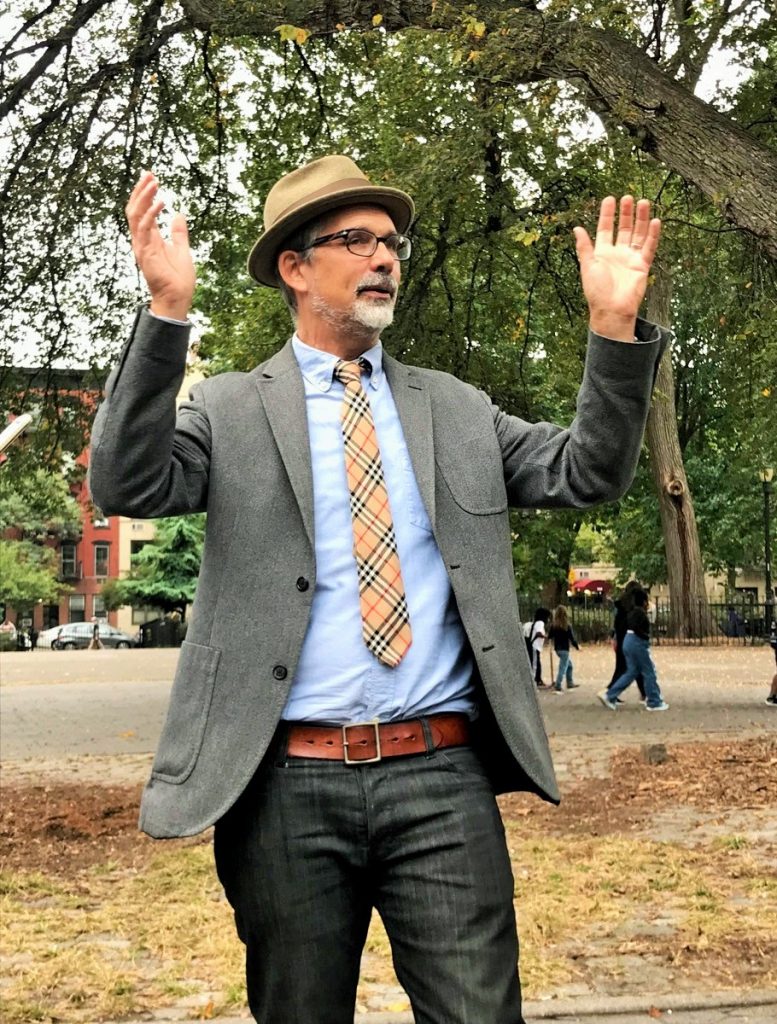

Clad in a gray blazer, thrifted Burberry tie and a fedora, with rectangular eyeglasses, Duncombe not only physically resembles the famed fictional lawyer, but he also parallels novelist Harper Lee’s vision for the morally righteous character: an individual with a strong urge for justice, equality and freedom for all.

A social activist and professor of media and culture at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, Duncombe’s about-to-be-released book, “The Art of Activism: Your All-Purpose Guide to Making the Impossible Possible,” delves into the creative and emotional power of the arts to invoke social change. Duncombe, who founded the Center for Artistic Activism in 2009, explores the importance of utopian thinking in this book and proffers a step-by-step method to the creative process of activism. He incorporates a hands-on approach to artistic advocacy, pulling examples from pop culture and modern media, and even includes a workbook with more than 50 exercises to practice.

“Instead of perpetuating an idea of artists as separate, magical beings, artistic activism allows us to cultivate the creativity we all already have,” he writes. “If we are going to build a better world, hell, if we are going to survive as a species, we need to change the world, creatively.”

Duncombe was raised in a family of activists. His father was a civil-rights demonstrator and a minister, whose fervor for advocacy came from his deeply religious Christian background. As Duncombe describes it, his father’s approach to activism was all about “peace and love.” However, Duncombe felt no connection to his father’s religious and political beliefs. In fact, his start in advocacy came from a very antithetical emotion.

“I was a really angry teenager,” Duncombe recalled. After stumbling upon the punk rock group the Sex Pistols, he felt a connection to the band’s anger.

“I couldn’t even understand what they were saying,” he said. “But I knew they were angry, and that it was O.K. for me to be angry. And from there, I discovered more political punk rock bands. So it was really punk rock music that got me into politics.”

Duncombe’s adolescent experiences allowed him to learn a larger lesson of how emotion can be invoked by the blending of art and activism.

“Activism has always been geared toward effect, making concrete changes to power structures and such,” explained Duncombe, as a college-age skateboarder whizzed past him. “Art has always been geared toward affect, touching people emotionally. And what we’ve tried to do [in this book] is combine the two.”

Standing in Tompkins Square Park, a treasure of the East Village known for being the epicenter of political demonstrations and historic protests, the 56-year-old reflected on his past approach to artistic activism, which stemmed from movements he took part in during his youth.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, members of the Lower East Side Collective and veterans of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) would regularly protest against what they saw as injustices in New York City, often implemented by then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Among them was Duncombe, whose inspiration for the book came from the peculiar and artistic demonstrations he took part in during this decade.

Following Giuliani’s quality of life campaign — a police crackdown aimed to restore the “quality of life” by imposing tough consequences for petty offenses and nuisances, such as public urination, public consumption of alcohol or possessing small amounts of marijuana — Duncombe and his group planned a mass protest in response. While the New York Police Department was expecting a typical protest — a march, chanting and then dispersal, as Duncombe describes it — this demonstration, in October 1998, left the police scratching their heads.

During the protest, Broadway — right in front of the N.Y.U. Tisch and Gallatin schools — was filled with more than 200 people dancing, with DJs booming music through a sound system on bicycle trailers. A man in a bright blue bunny suit, jugglers and fire breathers all brought this dance party to life, confusing N.Y.P.D.’s preconceived idea that this would just be a traditional protest. Except this dance party, called Reclaim the Streets, was a protest. It was an artistic act of demonstrating what the Lower East Side Collective was truly fighting for.

“Since so much of this campaign was about Giuliani’s quality of life, it demonstrated the world we wanted to bring into being,” Duncombe said. “In other words, we were demonstrating for the open use of public space. So why not use public space openly?”

Using his past experiences as a template, Duncombe, along with co-author and artist Steve Lambert, offers an inspirational structure for the concept of artistic activism, and displays how individuals can use this mechanism to create real-life change. In essence, Duncombe takes the theory of a marriage between art and activism and puts it into practice.

“When we think about artistic activism, it’s not just the object itself, it’s the approach,” Duncombe explained. “So what we do is we come up with [a] sort of methodology, which then you apply and develop your own tactics.”

This idea came from the work Duncombe has done all around the world with the Center for Artistic Activism. Russia, Kenya and China are few of the many countries Duncombe has visited, training more than a thousand activists on how to build an effective artistic campaign. His biggest takeaway: Context is key to building a sustainable movement and unique transformation.

“What works in New York does not work in Nairobi,” he pointedly noted. “You have to go do it with an eye for impact.”

Duncombe’s current focus has been on a much larger, pricier project. The Open Society Foundations, founded by controversial billionaire George Soros, has bestowed a $1.96 million grant on the Center for Artistic Activism. The money will fund the center’s national campaign aimed at combating the ongoing voting-rights violations taking place nationally today.

As he prepares for his new venture, Duncombe hopes that this book will inspire change among a broader audience. Moreover, he hopes that the book’s intended purpose — to serve a learning guide on how to use the fusion of art and activism — sparks change all around the world, regardless of one’s background.

“People can do it,” he said. “They’re creative, they’re active, and they can combine the two and they can transform the world. This is not a book of study and speculation. It’s a book of action, creative action.”

Funny, I always thought the word “doppelgänger” referred to a ghostly evil twin of a living person. Yet this piece, an exceptionally lavish plug for author/NYU professor/activist Stephen Duncombe, claims that its nattily attired subject could be a 21st century doppelgänger of Atticus Finch, a fictional lawyer so virtuous he practically puts Jesus to shame. How is this possible?