BY THOMAS F. COMISKEY |

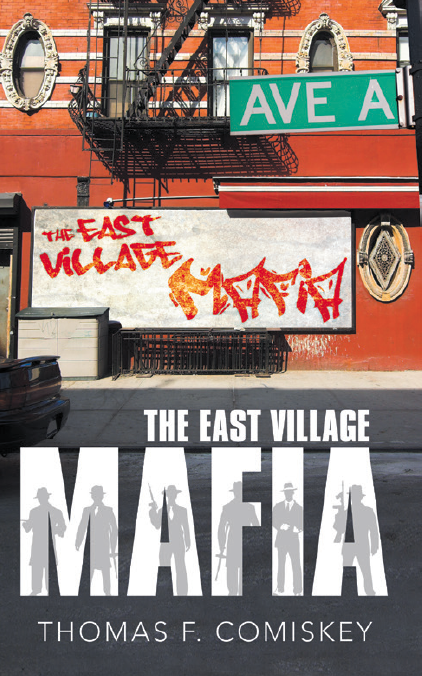

The following is Chapter One from former longtime Stuyvesant Town resident Thomas F. Comiskey’s new book “The East Village Mafia.”…

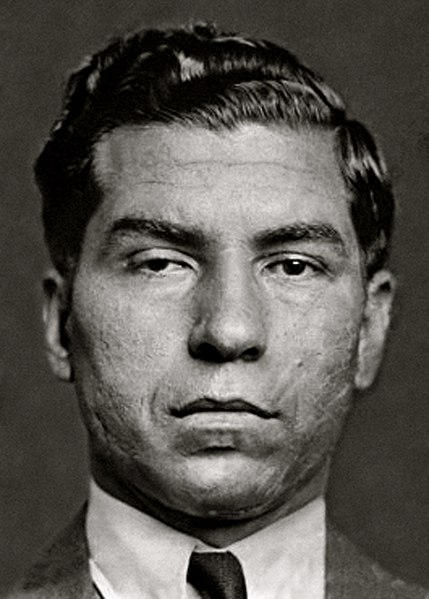

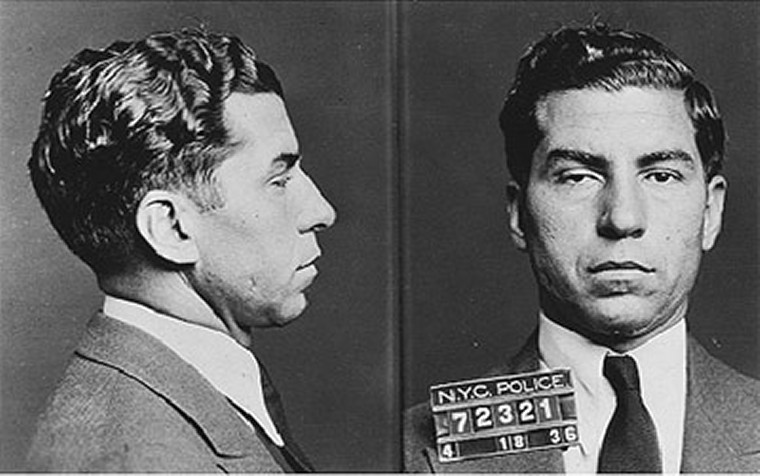

Charles “Lucky” Luciano, one of the most powerful and mythologized gangsters in American history, resided at 183 and 265 E. 10th St., between Avenue A and First Ave., for about 20 years, from 1907 to 1927.

Luciano is universally recognized for creating the modern-day New York City Cosa Nostra in 1931, after he arranged the murders of two consecutive reigning Mafia chieftains, Joe “The Boss” Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano.

Luciano instituted the Mafia Commission, a group of nationwide crime family dons who met every five years, or as necessary, to settle disputes between crime families.

Born Salvatore Lucania in Sicily, Luciano lived briefly on First Ave. between 13th and 14th Sts. before his family settled on E. 10th St. Luciano attended P.S. 19, on E. 14th St., currently the site of the 14th Street Y. Neighborhood legend has Luciano and Meyer Lansky hatching schemes together in De Robertis Pasticceria at 176 First Ave., around the corner from Luciano’s tenement.

As a teenager hanging out in Mulberry St. pool halls, Luciano was known as “Salvatore from 14th Street,” not for his school’s address, but because that was where he perpetrated his crimes, including selling heroin, burglary and auto theft.

His friends were a Who’s Who of future notorious gangsters, including Lansky, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel and Frank Costello. Luciano and Al Capone were reportedly groomed in the legendary Five Points gang, and “The Brain,” Arnold Rothstein, schooled Luciano in the finer points of bootlegging and narcotics peddling.

While Masseria and Maranzano discouraged doing business with non-Italians, Luciano set up lucrative criminal partnerships with non-Italian gang leaders like Meyer Lansky and Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, who were masters of gambling and labor racketeering, respectively.

Throughout the 1920s, Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, Albert Anastasia, Louis Buchalter, Frank Costello, Tommy Lucchese and Dutch Schultz, among others, hit the jackpot by bootlegging illegal alcohol during Prohibition. The upper echelon of organized crime gathered at Luciano’s Palm Casino, at 85 E. Fourth St., at Second Ave., to drink, gamble and solicit female companionship.

Luciano eventually outgrew the East Village. In 1927, he relocated to a suite at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel, which he rented under the guise of “Charles Lane.” Luciano later settled as “Charles Ross” in Suite 39C in the Waldorf Towers of the Waldorf Astoria.

Lucky Luciano’s rise to ultimate crime boss began on April 15, 1931, when he invited his boss, Joe Masseria, the reigning capo di tutti capi (“boss of all bosses”), to lunch at Nuova Villa Tammaro restaurant in Coney Island. Masseria, who was driven around town in a steel-armored sedan with inch-thick plate-glass windows, apparently felt safe in the company of his former chauffeur and bodyguard. After the meal, while Masseria, Luciano and two others played cards, gunmen burst into the restaurant and disposed of Masseria, who was found dead on the floor with four bullets in his back and one in his head. In a Mafia truth-is-stranger-than-fiction moment, an ace of spades was found clutched in Masseria’s hand. The New York Times described Masseria as a “mysterious power” and a “racket chief” who was “bigger than Al Capone.”

What Masseria did not know is that in a meeting witnessed by Joseph Bonanno, Luciano had switched sides to work with Salvatore Maranzano, Masseria’s enemy in the Mafia’s Castellammarese War of 1930–31. There has been endless speculation about the identity of the gunmen who eliminated Masseria. Luciano cronies Vito Genovese, Albert Anastasia, Joe Adonis and Bugsy Siegel are often mentioned.

One of the lucrative rackets that Lucky Luciano inherited from Masseria was the Italian lottery, or the numbers game. On March 30, 1935, detectives raided De Robertis Pasticceria and arrested Mike Sabatelli, described by The New York Times as a leading banker of the Italian lottery. The Mafia’s annual take from the policy racket was estimated between $2 million and $10 million. During a simultaneous raid at the Eagle Printing Company, at 202 E. 12th St., between Second and Third Aves., police found five million slips printed for the Italian numbers game. Each slip cost a nickel, and the average play was reported to be a quarter, with bets reaching as high as five dollars.

During and after Prohibition, Luciano and the other bootlegging chieftains knew that government and law enforcement officials had both hands out, palms open and up. Luciano and Lansky reportedly kept a million-dollar fund to pay off police, judges and everyone in between. Tammany Hall, the executive committee of the New York County Democratic Party, was the primary dispenser of jobs, contracts and judgeships in Manhattan. But Luciano didn’t have to pay off any Tammany Hall officials. He owned one.

In 1931, Albert Marinelli came to represent Manhattan’s Second Assembly District in Tammany Hall. The area included the Italian and Jewish neighborhoods south of E. 14th St. and surrounding Mulberry St. Gangsters had taken complete control of those precincts with their monopoly on the trade in Prohibition liquor, drugs, gambling and prostitution. Indeed, Marinelli was the titular owner of a trucking company run by Lucky Luciano during Prohibition.

Luciano’s gunmen reportedly in influenced Harry C. Perry to step down as co-leader of the Second Assembly District, resulting in Marinelli’s selection as the first Italian American district leader in Tammany Hall.

Next, Luciano installed Marinelli in the position of city clerk. With Marinelli under his thumb in that job, Luciano gained control over the selection of grand jurors, as well as the vote-count process during elections.

The 1932 Democratic presidential convention illustrates the degree to which Luciano engaged in political muscle flexing. Tammany Hall’s man was Al Smith, a former New York governor. His opponent was the current New York governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Lucky Luciano; his consigliere, Frank Costello; and Meyer Lansky accompanied the Tammany Hall delegation to the convention in Chicago.

Luciano roomed with Tammany delegate Albert Marinelli in a Chicago hotel suite, while Frank Costello roomed in another suite with Jimmy Hines, the Tammany Hall grand sachem from Manhattan’s Uptown 11th Assembly District. Hines was later convicted of providing legal and political protection for Dutch Schultz’s Harlem numbers racket, of which Hines got a share.

Luciano’s strategy was to split the Tammany delegates so that he would be kingmaker. Hines supported Roosevelt, but Marinelli and a small group of delegates abandoned F.D.R. and supported Al Smith. With Marinelli’s defection to Smith, Luciano hoped to gain leverage over Roosevelt, who needed the support of the entire New York State delegation to win the nomination. Yet Roosevelt did not want to openly embrace Tammany Hall, whose plunderings of the public and dealings with the Mafia were common knowledge.

Roosevelt issued a statement denouncing civic corruption while hedging that he had not seen enough evidence to support the prosecution of Tammany leaders. However, after winning the Democratic nomination, Roosevelt threw his support behind Judge Samuel Seabury’s ongoing investigation of Tammany Hall hacks. Seabury went on to reveal case after case of Tammany-controlled public officials with hundreds of thousands of dollars in savings, incompatible with their meager Depression-era salaries. Once elected, F.D.R. ended the century-old connection between Tammany Hall and the White House.

In October 1937, rackets Special Prosecutor Thomas Dewey alleged that County Clerk Albert Marinelli was “a political ally of thieves, thugs, dope peddlers and big-shot racketeers.” After Governor Herbert Lehman asked Dewey for evidence, Dewey’s staff interviewed hundreds of Marinelli’s underlings. Dewey was able to show the governor that Marinelli had consorted for years with Mafia powers Lucky Luciano, Vito Genovese, Joe Adonis and Socks Lanza, who controlled the Fulton Fish Market. On December 3, 1937, Marinelli resigned the county clerk office, and two days later, he was out as district leader.

Eventually, Luciano was convicted of being the leader of the city’s $12 million prostitution racket. He was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison on June 18, 1936. When the prison van took Luciano to Grand Central Terminal, 1,500 gawkers gathered on Vanderbilt Ave. to see Charlie Lucky go up the river to Sing Sing. Ten detectives and nine deputy sheriffs guarded Luciano and his codefendants.

On February 9, 1942, Lucky’s ship came in. The Normandie, a French luxury liner being converted into a troopship at Pier 88 on W. 48th St., caught fire, keeled over and was rendered useless. U.S. Naval authorities initially suspected sabotage, although that was later disproved. Four months later the F.B.I. arrested German saboteurs who had been deposited by submarine at Amagansett, Long Island and Florida. The U.S. Navy worried that it had a security problem on the waterfront, and it wanted to recruit eyes and ears there.

Naval Intelligence officers met with Joseph “Socks” Lanza, Mafia boss of the Fulton Fish Market, who had contacts with commercial fishermen, boat captains and seamen up and down the Atlantic Coast. Lanza said he wanted to help, but the Navy needed to speak to his boss, Lucky Luciano.

In May 1942, the New York State Department of Correction transferred Luciano from Dannemora, near the Canadian border, to the relative comfort of Great Meadow, near Lake George. Luciano met in prison with Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello and Albert Anastasia, among others, and ordered them to assist the Navy with security and intelligence gathering, both on the waterfront, and later, for the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943.

In January 1946, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, who had successfully prosecuted Luciano in 1936, commuted his sentence, citing his wartime aid. Luciano was released from prison and deported to Italy. But even from overseas, Lucky Luciano continued to cast a large shadow over the affairs of the Mafia, especially when it concerned narcotics.

There are persistent myths about the Mafia and drugs, C. Alexander Hortis explains in his book “The Mob and the City: The Hidden History of How the Mafia Captured New York.” One fiction is that the Mafia had a traditional ban against selling drugs. Another falsehood is that only younger, low-level members pursued the narcotics trade. Luciano was involved in the narcotics business for four decades, from his teens well into his 50s.

In 1914, New York State first outlawed cocaine and heroin trafficking. In 1916, at age 18, Lucky Luciano was arrested and served six months in prison for heroin possession. While making deliveries for a local drug dealer, Luciano dropped off a vial of heroin to a prostitute in a bar who turned out to be a police informant.

In June 1923, Luciano was arrested in a poolroom next door to Tammany Hall on E. 14th St., between Third and Fourth Aves. (the site of today’s Con Ed building), for selling morphine and heroin to a federal informant over a period of months. To avoid a 10-year sentence, Luciano told federal narcotics agents that his supplier had a stash at 163 Mulberry St. In fact, it was Luciano’s own narcotics supply, worth $150,000 on the street. For Luciano’s cooperation, the charges against him were dropped.

In December 1946, 10 months after the U.S. government deported him to Italy, Luciano convened a meeting of the Italian and Jewish heads of American organized crime in Havana, Cuba. The crime lords gave Luciano $200,000 in cash, and the Fischetti brothers from the Chicago Outfit reportedly delivered a suitcase to Lucky carrying $2 million. The Fischettis also brought along Frank Sinatra to entertain the conferees.

One of the most controversial issues discussed at the Havana gathering was the future of the narcotics trade. While the gangsters most involved in gambling argued against selling drugs, Luciano proposed a far-flung drug-smuggling network encompassing North Africa, Sicily, Cuba, Florida and Montreal. The ultimate destinations for the drugs would be New York City, New Orleans and Tampa because the Mafia controlled those ports. The Luciano and Mangano crime families (later, Genovese and Gambino, respectively) would control the narcotics shipped to the New York City docks. Joseph Biondo, who grew up on E. 14th St. and was a member of Luciano’s teenage gang, was selected to manage the narcotics business for the Mangano crime family. The East Village became the epicenter for the Mangano narcotics operation because that was where Joseph Biondo ran his crew of drug dealers.

The mobsters at the Havana Conference ultimately approved Luciano’s drug-smuggling and distribution plan.

The other action taken by Luciano at the Havana Conference that had dramatic repercussions for the Mafia was Lucky’s humiliation of his underboss, Vito Genovese. Luciano had promoted his consigliere, Frank Costello, to acting boss of the Luciano family after Luciano was deported to Italy. However, Vito Genovese felt that, as underboss, his time had come and he should be running the family. Luciano recognized the dangerous Genovese as a clear and present threat to his authority.

At the conference, Luciano reportedly made a motion to retain his position as the top boss in the Cosa Nostra. Albert Anastasia quickly seconded the motion because he felt threatened by Genovese’s attempts to muscle in on his waterfront rackets. The combined power of Luciano, Anastasia and Costello prevailed. Luciano arranged for Anastasia and Genovese to settle their differences by shaking hands in front of the other bosses. Luciano had boxed Genovese into a corner — for now.

According to “The Last Testimony of Lucky Luciano,” by Martin Gosch and Richard Hammer, at the end of the Havana Conference, Genovese met with Luciano in his room at the mob-run Hotel Nacional. Genovese told Lucky that the U.S. government was pressuring the Cuban government to expel Luciano, so he should turn over the leadership of the Luciano family to Genovese and retire in Italy. An incensed Luciano beat Genovese so severely that he broke three of his ribs. After Genovese recovered, Luciano and Anastasia put Genovese on a plane back to the United States.

In October 1957, Luciano, Sicilian Mafioso Santo Sorge, Mafia Commission Chairman Joe Bonanno, and Bonanno’s underboss, Carmine Galante, met with leaders of the Sicilian Mafia in the Grand Hotel des Palmes in Palermo, Sicily. The U.S. Narcotics Control Act of 1956 had legislated prison terms of up to 40 years for Americans convicted of drug dealing. According to Salvatore “Bill” Bonanno’s book, “The Last Testament of Bonanno: The Final Secrets of a Life in the Mafia,” it was agreed that henceforth the Sicilians would organize the smuggling of heroin into the United States, disguised as food exports.

Luciano’s friend Santo Sorge was related to Sicilian Mafia don Giuseppe Genco Russo. The confidential files of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (F.B.N.), predecessor to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, described Santo Sorge as one of the most important Mafia leaders. He traveled frequently between Italy and the United States to liaison between top Mafia bosses. The Santo Sorge Trading Company, at 196 First Ave., between E. 11th and 12th Sts., was cited by the F.B.N. in 1948 as complicit in the smuggling of Sicilians carrying heroin to Philadelphia by ship.

While Lucky Luciano was tending to his heroin trade in Italy, Vito Genovese was exacting revenge for his belittlement at the 1946 Havana Conference. On May 2, 1957, Genovese dispatched his chauffeur/bodyguard, Vincent “The Chin” Gigante, to eliminate Luciano’s surrogate, Frank Costello, the mob’s “prime minister.” In the lobby of Costello’s apartment building, The Majestic, at 115 Central Park West, between W. 71st and 72nd Sts., Gigante shot Costello in the head, but the bullet only grazed his skull. Costello fully recovered.

At trial, Costello refused to identify his assailant, and Gigante walked free. “The Chin” — who would go on to live at 505 LaGuardia Place, between W. Houston and Bleecker Sts. — would later attain tabloid infamy as “The Daffy Don” and “The Oddfather.”

Next, Genovese enlisted Albert Anastasia’s underboss, Carlo Gambino, to assassinate Anastasia, a Costello ally who controlled several hundred soldiers. On October 25, 1957, two gunmen riddled Anastasia with bullets in broad daylight as he sat in a barber’s chair in Midtown Manhattan. Frank Costello retired from the life soon after.

Less than a month later, Genovese called together the Mafia hierarchy to declare himself capo di tutti capi. On November 14, 1957, about 60 of the nation’s mob bosses convened in a countryside mansion in Apalachin, New York. A local state trooper observed a fleet of luxury cars descending on the sleepy town, so he blockaded the roads leading to the mansion, whose owner the trooper knew to be “connected.” Dozens of Mafia dons, underbosses and consiglieri fled into the surrounding woods and cold mud in an unsuccessful attempt to escape. Some Mafia experts claim that Luciano and Meyer Lansky, who did not attend Apalachin, tipped off local law enforcement to get back at Genovese.

In the end, Genovese’s coup d’état was a spectacular failure. The other mob leaders, many of whom were previously unknown to the public, were now subpoenaed and accused in hearings of being part of a nationwide criminal conspiracy. The top Mafiosi were exposed, and in their minds, Genovese was to blame. Widespread press coverage of the national Mafia conclave at Apalachin also forced J. Edgar Hoover to devote substantial F.B.I. resources to investigate the Mafia. Previously, Hoover was obsessed with uncovering post-World War II Communist conspiracies. He had let the Federal Bureau of Narcotics take the lead on Cosa Nostra.

In 1959, Vito Genovese was convicted on federal narcotics conspiracy charges and sentenced to 15 years in prison, where he would die. The heroin trafficking ring that ensnared Genovese operated locally from a bar and luncheonette on E. Fourth St. in the East Village. According to mobster Doc Stacher, Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano had paid $100,000 to a Sing Sing inmate, Nelson Cantellops, to alert the F.B.N. to the intimate details of the narcotics import ring, including 24 names of Don Vito’s cronies, dates and locations. The F.B.N. arranged Cantellops’s release from prison, and at trial he was the star witness against Vito Genovese.

In a final bit of irony for Genovese, Carlo Gambino’s family surpassed the Genovese borgata in wealth and power in the 1960s. Gambino had reportedly contributed $25,000 to the $100,000 paid to Nelson Cantellops to destroy Vito Genovese.

In 1960, 14 years after Lucky Luciano was deported to Italy, he had settled in Naples — but he still pined for his favorite East Village haunts. Luciano unwittingly befriended an undercover F.B.N. agent, Sal Vizzini, who was posing as a U.S. Air Force pilot. Luciano advised Vizzini that when he visited New York, “Go to the Reno Bar on Second Avenue between 11th and 12th and ask for Butch Salerno. Tell him I send my regards.”

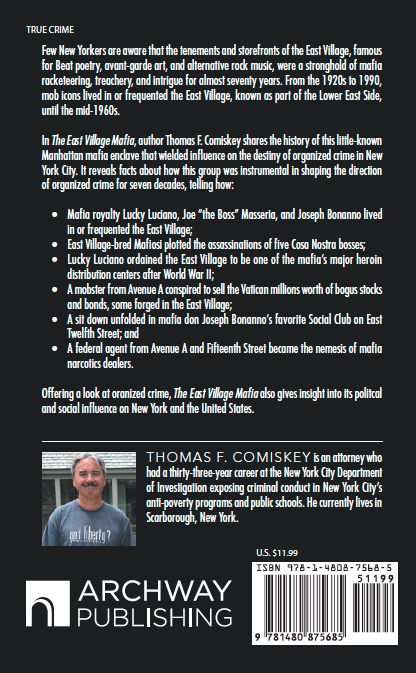

Comiskey is an attorney and had a 33-year career at the New York City Department of Investigation exposing criminal conduct in New York City’s anti-poverty programs and public schools. He lived in Stuyvesant Town from 1953 to 1990 and currently lives in Scarborough, N.Y.

In other chapters in “The East Village Mafia,” Comiskey relates how East Village-bred Mafiosi plotted the assassinations of five Cosa Nostra bosses; a mobster from Avenue A conspired to sell the Vatican millions worth of bogus stocks and bonds, some forged in the East Village; a sit-down in Mafia don Joseph Bonanno’s favorite social club on E. 12th St. determined control over a New Jersey hotel; and a federal agent from Avenue A and 15th St. became the nemesis of Mafia narcotics dealers.

“The East Village Mafia” (126 pages, Archway Publishing, March 2019) is available on Amazon for $11.25 and also by e-book download for $3.

Be First to Comment