BY MARY REINHOLZ | New York journalist Stanley Mieses, the son of Holocaust survivors and a former longtime writer for The New Yorker who witnessed the Twin Towers collapse from his Tribeca apartment and described the devastation in the surrounding neighborhood for National Public Radio, died last month at a Downtown Manhattan Hospital. The cause of death was from the effects of COVID, pneumonia and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder (COPD), according to close friends.

Mieses was 70 and had lived his entire life in varied city neighborhoods. His last stop was in Jackson Heights, Queens. A crony said Mieses bought a condo there in 2006 after a steep rent hike was imposed on his West Broadway studio next to the Odeon restaurant.

Mieses apparently contracted COPD by exposure to toxic chemicals and dust while living six and a half blocks from Ground Zero. He died Feb. 3 at Beth Israel Hospital, on E. 16th Street, where he had been sent by his doctor, said David Wallis, who once wrote for Mieses at New York Newsday and then became his editor at the New York Observer.

Wallis organized a GoFundMe campaign to raise $12,000 for Mieses’s burial, a Jewish service and a headstone at the Jewish/Austrian section of Mount Moriah Cemetery in Fairview, N.J., where his parents were buried.

“We had to act quickly because he died unexpectedly with few relatives left and he did not leave a will or any instructions” on where he wanted to be laid to rest, Wallis said. “It was a helluva situation.”

At last count, $8,000 had been raised by donations from more than 100 people, “all from Stanley’s family of friends,” Wallis said in a phone conversation with The ViIlage Sun, noting their contributions got Mieses “out of the morgue” on Feb. 14 and into his spot at Mt. Moriah. Five other friends helped Wallis organize the burial.

Around 40 friends of Stanley Mieses gathered for a March 14 evening memorial for the veteran writer and editor at the Greenwich Village apartment of author Susan Shapiro, a New School writing professor, and her husband, television writer Charlie Rubin, a New York University professor.

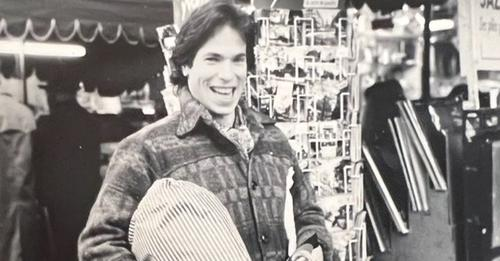

Shapiro said most of the guests were friends and colleagues from the publications that employed Mieses in full-time jobs, notably The New Yorker, where he had penned pieces for its Talk of The Town section for 13 years. He was also a Part II features editor at New York Newsday and a book editor at the New York Post. Early in his career, he moved from copy boy to music columnist for the New York Daily News, later working for Atlantic Records and touring with the rock band Kiss, Shapiro noted in a tribute for Salon.

In her remembrance, she called Mieses a “mentor” and one-time romantic interest who had rescued her career after a job loss, and said he helped many struggling writers in the city. Shapiro also described him as “catnip to women,” who had an “illustrious reputation of leaving broken hearts strewn across all five boroughs.”

Virginia “Ginny” Reath recalled humorous anecdotes about Mieses in the neighborhood and how they met.

She related how Mieses at one point lived on Sullivan Street right across from St. Anthony’s Church. During the Feast of St. Anthony Day, the devout were marching in the street, carrying a blue-robed statue of the saint, to which they had pinned money. Mieses, freshly out of the shower, dripping wet and unclothed, appeared at his window and made eye contact with a female. They both had their mouths agape. Everyone became entranced looking at both of them looking at each other. Suddenly, the girl, who was about 14, shouted at Mieses, “Whatcha lookin at? You f—in’ fairy!” and he immediately ducked down.

Reath said she first met Mieses when they bumped into each other at the M&O Deli on Prince Street. He was wearing a funky hat and outfit and platform boots and she made a quip about him really needing to dress a bit more expressively. Later that day she found a note in her mailbox from Mieses that simply said, “Meet me at Butterfingers” and gave a time later that night. When she arrived at the Upper East Side restaurant, she found him — in what she called a classic Stanley — stuffing his pockets with shrimp, and learned they were going by white limousine to the premiere of the movie “The Man Who Fell to Earth” at the Coronet Theater.

Another friend, Carol Klenfer, who did P.R. for top rock bands, recalled a zany story of the time Mieses was going to do an interview for the National Star of the lead singer of a hot new Boston group.

The singer, Steven Tyler of Aerosmith, finally emerged only to admit, “Man, I’m wasted off my ass on acid.” They wisely called the whole thing off.

At another point during the memorial, Shapiro shared, “The funniest RSVP I got was [asking] where to send a pound [of pot].” Writer Arthur Levy chimed in that the weed should be used to help pay for the burial.

Learning that friends were continuing to raise money for Mieses’s headstone made this jaded newsie snivel as I remembered the man’s kindness and empathy for other people. I had written for one of his predecessors at New York Newsday and met with him at its Manhattan office in 1993 about six months after I had been summarily fired right before Thanksgiving during a tryout on an Eastern Long Island weekly. Mieses made it plain he was interested in my ideas.

“I would be predisposed to look at an article on Ron Kuby,” he said to me in a majestic baritone when I pitched profiling the rising ponytailed criminal defense lawyer. He headlined Kuby in my published piece as the “Hair Apparent” of civil liberties icon William Kunstler, his Greenwich Village partner.

Stanley published two other articles I wrote for him despite his telling me much later that he knew I had “fallen out of favor” years before with his Long Island supervisor. So I knew early on that Stanley Mieses had guts before we became personal friends when New York Newsday folded in 1995. I also knew he was a vulnerable and sensitive man in a brutal business, living in a city that was nearly brought to its knees on 9/11 when two hijacked planes slammed into the Twin Towers.

More than a decade later, Mieses began receiving treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder funded by the James Zadroga Health and Compensation Act, controversial legislation signed by President Obama in 2011 and named after a police officer who had worked amid the Lower Manhattan wreckage and later died allegedly from breathing problems.

That same year, Mieses told The New York Times that the police evacuated him from his West Broadway studio but that he would return every few days to feed his cats.

“Dead people were blowing into my apartment off the windowsills,” he said, remembering the ash, “because the landlord was too cheap to clean it.”

In another interview, Mieses told the now-deceased Neal Conan on NPR that 9/11 affected him more than the death at 80 in February of that year of his Berlin-born mother, Charlotte Mieses, a retired Dean Witter executive, who was taken to England via Kindertransport in 1939 and emigrated to New York in 1947. Her late husband, Janusz, born in Austria, escaped the Nazis by joining the French Foreign Legion and became a furrier when he emigrated to New York City. Their only child, Stanley, spoke German, Spanish and Yiddish. He graduated from Boston University.

My way of keeping Stanley Mieses alive is reading his published work, most recently what I could get from a May 1978 Talk of the Town piece in The New Yorker about a counterman named Leo Ratnofsky who was retiring after 40 years at B&H Dairy, at 127 Second Ave., in the East Village. Ratnofsky recalled how that Downtown roadway was once like a “Yiddish Broadway.” Mieses recounted how the counterman spent his last day at B&H squeezing five cartons of oranges starting at 5 a.m. in the morning and working a total of 14 hours.

“I’m just an old-fashioned worker,” he told the writer, who seemed to understand him. “Look, can I get you a glass of juice, or something?”

With reporting by Lincoln Anderson

I met Stanley in Junior High School — we ran against each other for seventh grade vice president (he won, of course). We become fast friends — coming from similar family backgrounds. Over the years, we drifted apart and then back together for brief moments. Our meetings were always connected to our families’ histories, and we would discuss the effects it was having on us at various stages on our lives. Much of what was written here about Stanley, I did not know — we had not been in each other’s lives in other than one way since adolescence. But we could always check in. It was back in October that I started to look for him. I am very sad to hear of his passing — I miss talking to him. May his memory be for a blessing.

Stanley was a memorable man in so many respects. Also a terrific writer and friend. Truly sui generis, one of a kind. I share your sadness at his far too early passing.

Rest in Peace Stan the Man. My sister knew you better than I did. You were always good company.

Both gone too soon. Pat O.

I met Stan in 2014 and knew him until we lost touch in late 2022. I did not know he passed away until I couldn’t reach him during the holidays as he crossed my mind. And now I know why. He was a great person and I know the world lost a great spirit.

I just learned of Stanley’s passing. He was a wonderful man. I didn’t know about his death. I’m devastated. I loved that man. He had a beautiful spirit. He’ll be so missed…

It has been a while since we had last talked and it wasn’t the friendliest exchange, but you did make an impact on my life and will live on in my memories. You are gone too soon, but I am glad you were in my life for the time that you were. Goodbye, Stanley, but not forgotten.

I loved Stanley and today after weeks of being unable to reach him via phone fearfully googled “Stanley Mieses obit,” and thus learned of his death.

My mother Lilli was Lotti’s best friend in Berlin elementary school to the time that both of them were sent to England via the Kindertransport.

When we emigrated to Washington Heights from the UK, my mother and Stanley’s mom reestablished their “bestie” relationship. I became Stanley’s big brother (although both of us were our parents’ only child), a position I proudly held throughout his life.

I shall miss our calls and emails, I shall miss the opportunity to visit when in NY. I shall miss my last connection to Yekke’s of a certain time and Stanley’s wit about our fathers’ escape in Cuba from the French Foreign Legion and my father’s escape from Sachsenhausen.

I’m ten years older than Stanley and one doesn’t meet new friends who shared your past from 1955 to the present. I shall miss our lengthy discussions about pickles, pastrami, borscht, politics and books.

I shall miss him and cry — Stanley faced difficulties in his journey.

I can only hope that some Rabbi is right and that he’s now seated with Lotti and Jonnie in a heavenly deli.

David Wilzig

Stanley was an old friend of mine back in the 1980s. When I first visited his ramshackle Downtown loft, I remember asking him if it had mice. “No, just Mieses,” he calmly replied.

I never met Stanley but I’m acquainted with a few who knew him mentioned in this article. I appreciate this account of his journalistic life and contribution to Downtown NYC.

I remember meeting Stanley in his book-filled apartment in Tribeca just above the Odeon diner. Gone too young.

I met Stanley during his stint on Sullivan Street. He’d grab a coffee — a regular with a few other regulars from the ’hood at Augies… a coffee bean joint with about 3 seats — you could also get a coffee to go…very bare bones.