BY MARY REINHOLZ | A day after acclaimed California-born author Joan Didion died at 87 in her Upper East Side apartment on Dec. 23 from Parkinson’s Disease, I visited the Strand Downtown, looking to replace my tattered copy of her 1968 collection of essays, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” elegantly written pieces for Life magazine, the National Review and the Saturday Evening Post. The title story is a much-admired account of young hippies in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, among them a 5-year-old girl reading a comic book high on acid.

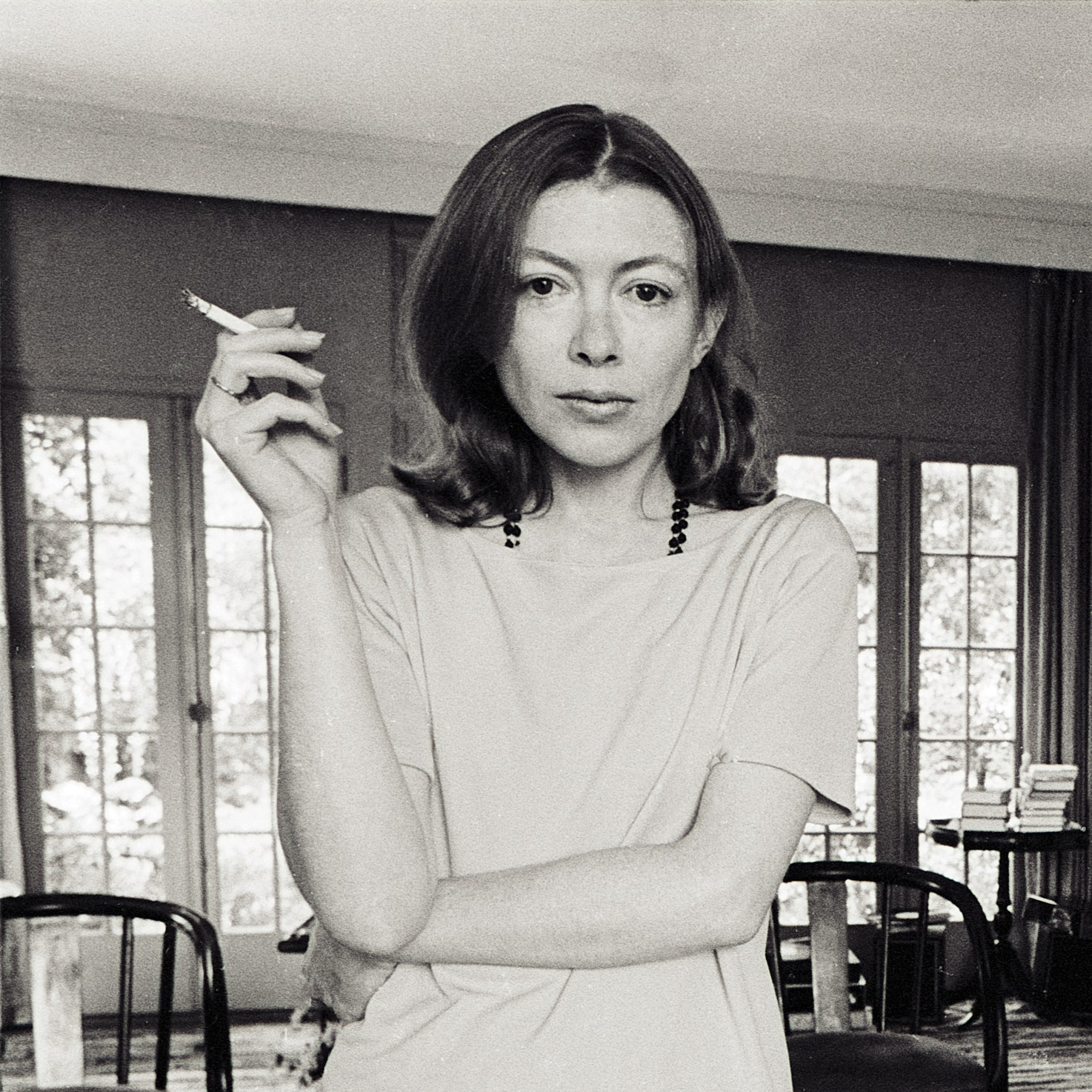

Delivered with Didion’s signature cool and dispassionate prose, the collection became a literary sensation, thrusting the shy, 5-foot-tall, wraithlike wordsmith into a pantheon of male-dominated “New Journalists” of the era, up there with flamboyant big boys like Hunter Thompson, Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese, who also used fictional techniques to capture changing lifestyles during a tumultuous time in America.

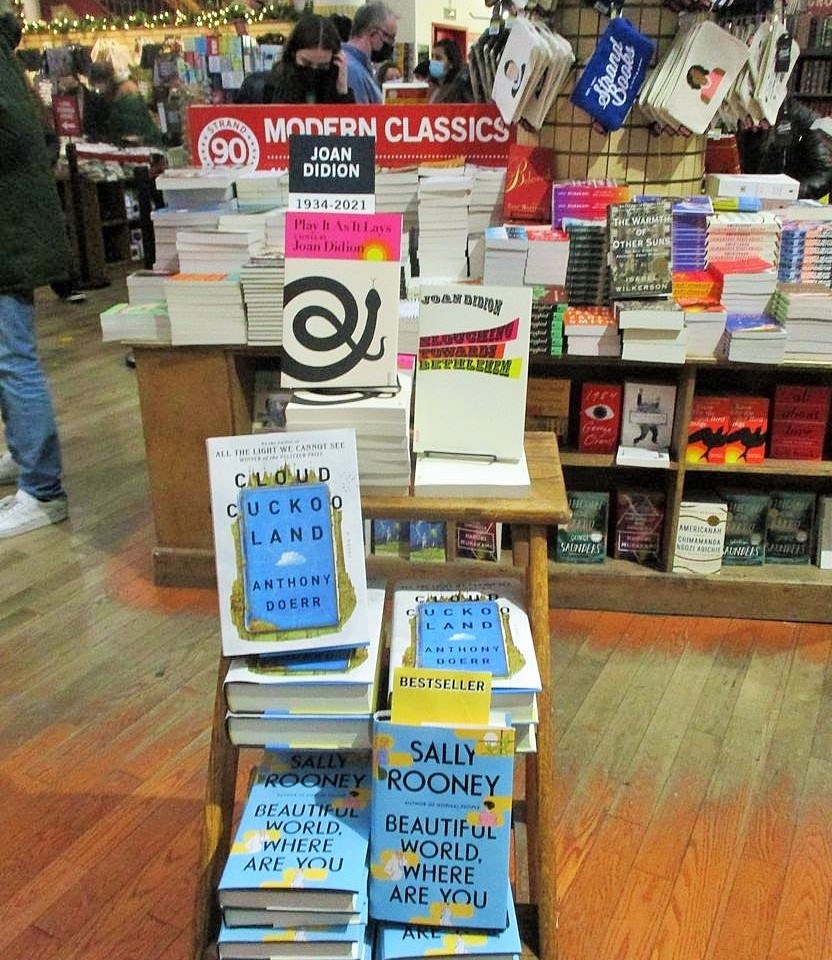

There was nothing available by Didion that day I dropped by the Strand. I wanted to ask Ben McFall, the store’s legendary fiction seller, if Didion had fallen out of favor with bohemian book buyers and had maybe been overpraised for her work over six decades. Her body of work included 16 books, one play and seven screenplays, the latter co-written with her late husband of nearly 40 years, author John Gregory Dunne. But I couldn’t see McFall at his familiar spot on the first floor and quickly left, later learning online that he had died at 74 on Dec. 22, one day before Didion expired.

Didion would certainly understand the intense mourning for McFall and the shrine set up for him in the back of the store and tributes calling him the “heart” of the iconic Strand, where he had proudly worked for 40 years. After all, she had lost John Dunne in 2003 shortly after they had visited their adopted daughter Quintana Roo in a Beth Israel emergency room. They were sitting down for dinner at their apartment when he abruptly collapsed at the table, fatally stricken by a heart attack at 71.

“Life changes fast. Life changes in an instant,” she observes in her most celebrated book of nonfiction, “The Year of Magical Thinking,” a 2005 bestseller which won a National Book Award. “You sit down for dinner and life as you know it ends.” The book was adapted into a one-woman play on Broadway starring Vanessa Redgrave. In a related tragedy, Didion penned “Blue Nights,” about the passing of her daughter Quintana Roo at 39 two years after Dunne died.

When I stopped by the Strand again early in January, there were only two of Didion’s books, both in paperback, on display on the stepladder in front of the store: “Slouching” and “Play It as It Lays,” her 1970 novel about a movie starlet in her 30s who roams the serpentine Southern California freeways in her car to escape psychic pain. It was made into a movie starring Tuesday Weld. By then some reviewers were beginning to view Didion as a fragile creature, beset with migraines and premonitions of doom, a “neurasthenic Cher,” as her fiercest critic, Barbara Grazutti Harrison, put it.

More recently, Gay Talese, a granddaddy of the New Journalism, called Didion a “brilliant communicator” but “understated” in person and also “guarded” and “withdrawn” in her dealings with the outside world. But he remembers her opening up at a late-1970s dinner to which he had been invited with “six to eight” other guests at her tony home in Malibu. Didion was doing the cooking and “conversing freely and enchantingly as we stood around, drinks in hand.”

In an e-mail, Talese noted: “One never uses ‘charming’ to describe the understated and withdrawn Joan Didion; but that is how I remember her from that night so long ago, and continue to remember her today.” (Both Didion and Talese were the subjects of 2017 documentaries released by Netflix.)

The only time I interviewed Didion was in 1987 for the New York Daily News after she had published a second book of political essays, this one on Cuban exiles in Florida called “Miami.”

“The CIA trained [the exiles] in 1961 for the Bay of Pigs,” she asserted, alluding to the aborted invasion by die-hard opponents of Fidel Castro, the bearded Cuban leader whose revolution took power in 1959. “At the University [of Miami] they were running a big operation. I think there’s a lot of stuff we haven’t wanted to look at. There’s a lot of stuff that nobody wants to know or to examine very closely.”

Didion was indeed guarded but answered all of my questions and laughed easily, sometimes flashing a caustic wit.

Her late longtime writer crony Nora Ephron said at the time that Didion was “not at all what people think of her. A lot of people see quite clearly her sensitivity but for reasons completely mysterious to me, they also don’t see that she is very funny. The first night I met her, she was wearing a short white backless dress that turned out to be the dress she had gotten married in.”

Few of the tidal wave of tributes for Didion mention that she was no friend of feminists. Her 1972 attack on the women’s movement, published on the front page of The New York Times,accused second wave feminists of espousing a “simple” Marxist view of women as an oppressed “class.” She also claimed that the radical sisters had “trivial “complaints — such as feeling humiliated by construction workers “observing” them on the street. None of that made sense to me since the often-hooting and hectoring hard hats obviously did more than “observe.”

Born into a conservative fifth-generation Sacramento family (she voted for Barry Goldwater at age 30), Didion graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, with a degree in English in 1956 and went to work for Vogue in Manhattan after winning a writing contest sponsored by the elite fashion magazine. She apparently changed her political leanings over the years and has been credited as the first mainstream writer to suggest that the Central Park Five were wrongly convicted. (They were later exonerated).

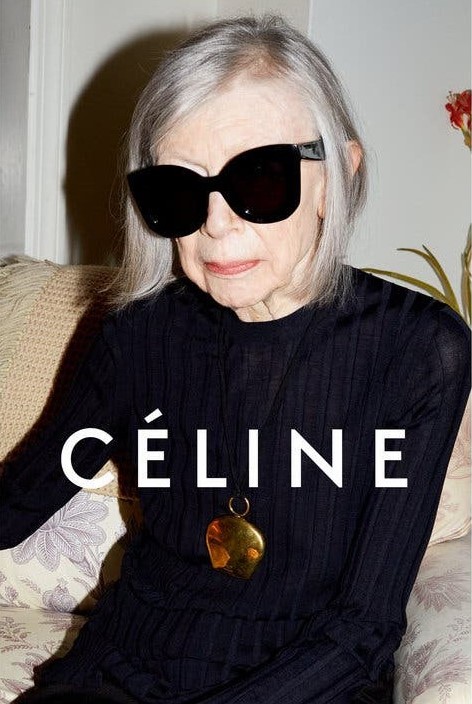

For a younger generation of fans, she’s the idiosyncratic grande dame who bought Linda Kasabian a dress to wear at Charlie Manson’s trial and who later posed for a Celine ad in old age.

At least one of the literary obits for Didion claims she “owned” Southern California, capturing its existential dread and violence on nights when the fearsome Santa Ana wind blows.

The Santa Ana is present in her devastating crime story in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” about a housewife and mother named Lucille Maxwell Miller. Miller was convicted of murdering her sleeping dentist husband by dousing him with gasoline and setting him on fire in their Volkswagen during a nighttime drive to get some milk (and allegedly his insurance money).

This piece, titled “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dreams,” shows Didion at her mordant best, in my honest opinion. However, some critics have claimed “Dreamers” also shows a snooty sensibility that looks down on working-class people in the San Bernandino Valley.

“This is the California where it is easy to buy Dial-a-Devotion but hard to buy a book,” Didion writes, noting it is also “the country of the teased hair and the Capris and the girls for whom all of life’s promise comes down to a waltz-length white wedding dress and the birth of a Kimberly or a Sherry or a Debbi and a Tijuana divorce and a return to hairdressers’ school.”

More selections from the author’s oeuvre were conspicuously on sale at the Barnes & Noble in Union Square, where an entire table on the first floor was filled with both paperback and hardcover volumes during my last visit.

“After her death, we just sold out immediately,” said Jessie, a young bookseller.

Jesse was surprised to learn that Didion was not part of the women’s liberation movement. In death, as in her life, Joan Didion remains a mystery. I’m guessing she wouldn’t want it any other way.

An excellent, penetrating evaluation of the late literary fave. Very fair, balanced, well written.