BY H.D. WRIGHT | On the fifth floor of 210 Fifth Ave., Ngo Okafor scrolls through a playlist on his phone.

“I only play hip-hop and Afrobeats here,” he assures me.

He taps the cell’s screen and music whirls into the space at Iconoclast Fitness — Okafor’s self-made training studio — blending with the city’s white noise filtering in through the windows.

Okafor sways slightly, in time to the tune, and smiles winningly. The celebratory tone of the music, coupled with Okafor’s resonant confidence, conveys a sense of ease; yet very little in Okafor’s life came without struggle.

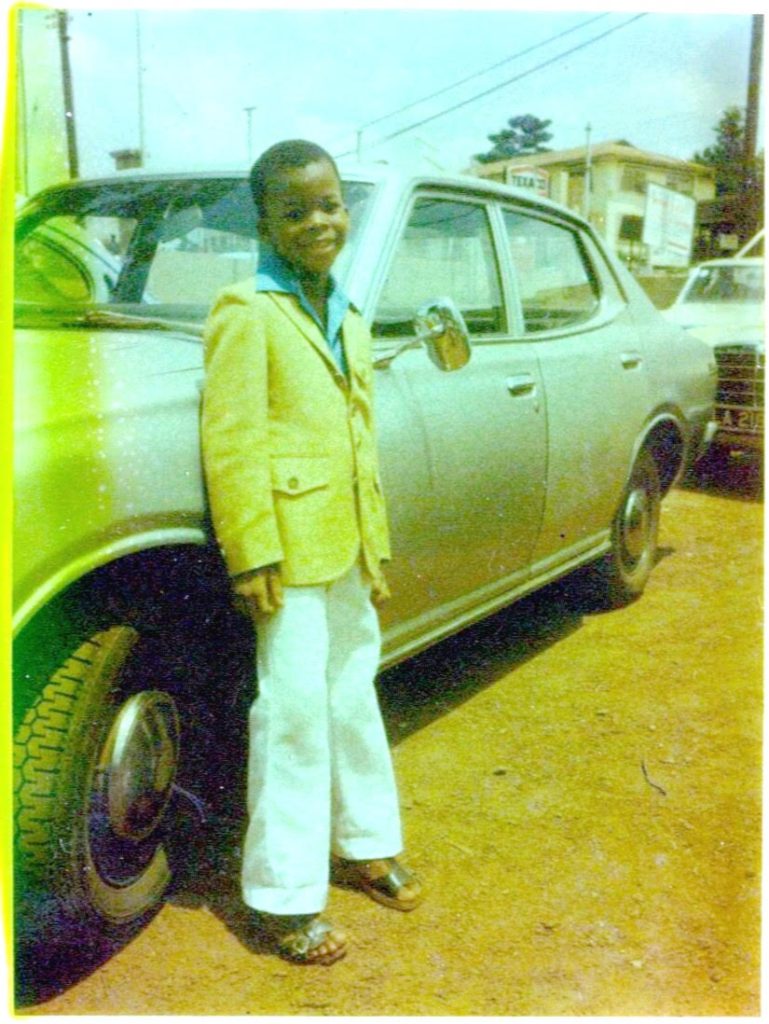

He grew up in Enugu, the capital city of Enugu State, Nigeria. From an early age, he was afflicted with respiratory illnesses — asthma, pneumonia and intense allergies — and was frequently ferried to the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital.

“There was little light, and the sounds of construction filled my wing,” Okafor recalls. “I liked when the patients smoked because it killed the synthetic smell. The rubbing oil, the alcohol, the cleaning agents — it was always so antiseptic.”

To pass the time, Okafor read “David Copperfield,” “A Tale of Two Cities” and “Oliver Twist.”

“London is so dark and gray,” he reflects on the Dickensian world. “And then you throw poverty on top of that, it’s more gray when you have no money.”

At 13, Okafor came home, exchanging a hospital bed for a suffocating household.

“My parents were ridiculously strict,” he says. “I felt like I couldn’t live my life in that house.”

Okafor skipped three years of school, studied for the university entrance exam and enrolled in college at 15.

“I knew that if I got into college, I could leave home.”

Classes were monotonous for Okafor, who preferred the euphoric vertigo of parties. Even though he had left hospital life behind, and settled into routine amusement, he wanted to begin again. He wanted to seek a new life in the United States.

“There was unrest in Nigeria. There were tanks in the streets. People thought another civil war was coming. So we said, ‘Let Ngo go, so at least one of us is out.’ All of us convinced my father to let me go.”

At 18, Okafor flew to Vernon, a small town in northeastern Connecticut, where his aunt and uncle were waiting. Only three months after his arrival, though, his relatives announced they were leaving for Canton, Ohio.

Okafor had already made friends in Vernon and enrolled at the University of Connecticut; so he stayed in the dorms.

Okafor had already made friends in Vernon and enrolled at the University of Connecticut; so he stayed in the dorms.

“I was finally free,” he exhales.

Years passed, work shifted and changed, and at age 31, Okfar began to box at the New York Health and Racquet Club on 23rd Street and Sixth Avenue. He fought for pure enjoyment, for the love of feeling his fists hit the bag, until a chance encounter: Amidst the amateurs Ngo glimpsed an athlete.

“He was so smooth,” he recalls. “He hit the bag so fluidly. I wanted to move like that.”

Okafor asked what the man was training for. The Golden Gloves, he responded. Intrigued, Okafor waited for him to finish, then challenged him to spar. Though the man politely refused, he did offer to set Okafor up with his trainer.

That evening, they walked to Kingsway Boxing, at 1 W. 28th St. To test his skills, Okafor’s new trainer insisted that he spar with someone, a heavyweight from the same city in Nigeria.

“He was swinging hard shots,” Okafor relates. “He was trying to kill me. I ran for my life the whole way.”

Despite the disadvantage of starting to train seriously at an age when most amateur boxers retire, Okafor resolved to continue.

“It was an opportunity to express myself athletically,” he explains. “I could perform. That’s what kept me going.”

Over time, Okafor’s hands hardened, his arms extended and retracted with more speed, and that single shock of potential energy — which begins in a pivoting ankle, travels up the leg, whips at the hip and finds its force in an outstretched fist — crushed past the coarse fabric of the bag to its soft center. Okafor was ready for more.

Six months after he joined Kingsway Boxing, Okafor signed up for his first Golden Gloves bout. Within the first few minutes, his opponent clipped him in the face. Okafor stumbled, and the fight was stopped. Okafor had lost. Incensed that the referee hadn’t given him a chance to recover, Okafor trudged home, and pushed his gloves to the back of his closet. He didn’t box for a year.

“I went to work and focused on my training business. But I didn’t want losing to be my legacy.”

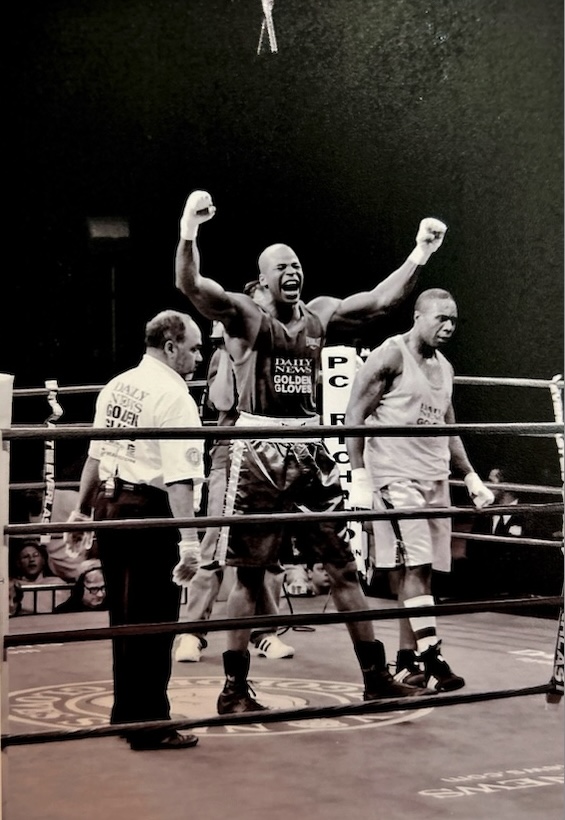

So he came back to the gym, to the sparring partners’ jabs at daybreak and to the bag in the evenings. That year, Okafor won the Golden Gloves Novice Division at Madison Square Garden. The next year, he won the Open Division.

“I used all the anger from the losses to drive me,” he says.

In the aftermath, Okafor settled permanently in New York, buying a space for a training studio in the Flatiron District, eight blocks from Madison Square Garden. In the studio’s early days, new trainers, according to Okafor, were stiff and accustomed to rigid rules.

“They always kept their eyes down,” Okafor remembers. “But now when I walk around here, I can see everyone’s eyes. They’re smiling, and the shackles come off.”

To Okafor, the space symbolizes freedom.

“I want people to free themselves, in every sense of the word,” he stresses. “If you free your body, you free your mind. And if you’re free, you want to share, because you want other people to be free, too.”

Although the fighting happens in the ring, sometimes it happened over…the choice of music. Once, a client asked Okafor if he could shuffle the tunes selection. Another insisted that Okafor turn the music off, because, in his words, “It’s what animals listen to.”

Okafor argues that the gym is living proof that Black people are peaceful, that they work hard.

You hear this music that’s supposed to be for animals,” he scoffs. “But you cannot ignore the beauty of the space and the positive energy. And you cannot ignore me.”

Okafor’s clients agree. Satenik Davidkhanian, an Iconoclast Fitness regular, says, “Ngo calibrates each session to the personal and physical needs of his clients. His kindhearted spirit infuses the studio with such positivity.”

Marin Hopper, a designer, flew in from Los Angeles and joined Davidkhanian’s most recent session.

“What is most striking about Ngo is that he shares his wealth of experience,” she notes, “not only as a trainer but also as a boxing champion — and applies it to helping his clients address any physical challenges they may need to overcome.

“I have suffered for years from a neck injury, and Ngo provided me with innovative ways to strengthen that area, while addressing my overall fitness regimen.”

Okafor’s boxing studio transcends personal pressures and racial prejudices, providing a meeting place for iconoclasts outside — or five stories above — the urban maelstrom. He recognizes that even as clients leave the outside world behind, the marks of old wounds will not disappear at his doorstep.

“If I can get you to look better on the outside,” Okafor offers, “then you can have the confidence to deal with the damage on the inside.”

This is such a great article! A true testament to his life journey and why he is dedicated to helping people feel better about themselves. I loved training with Ngo!