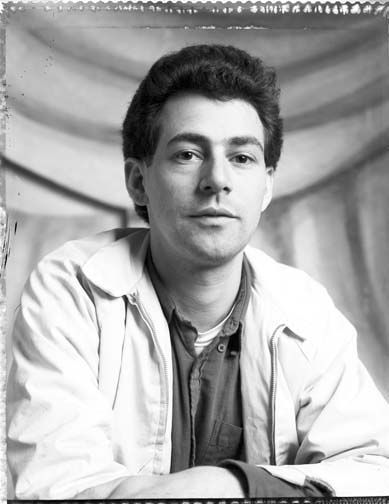

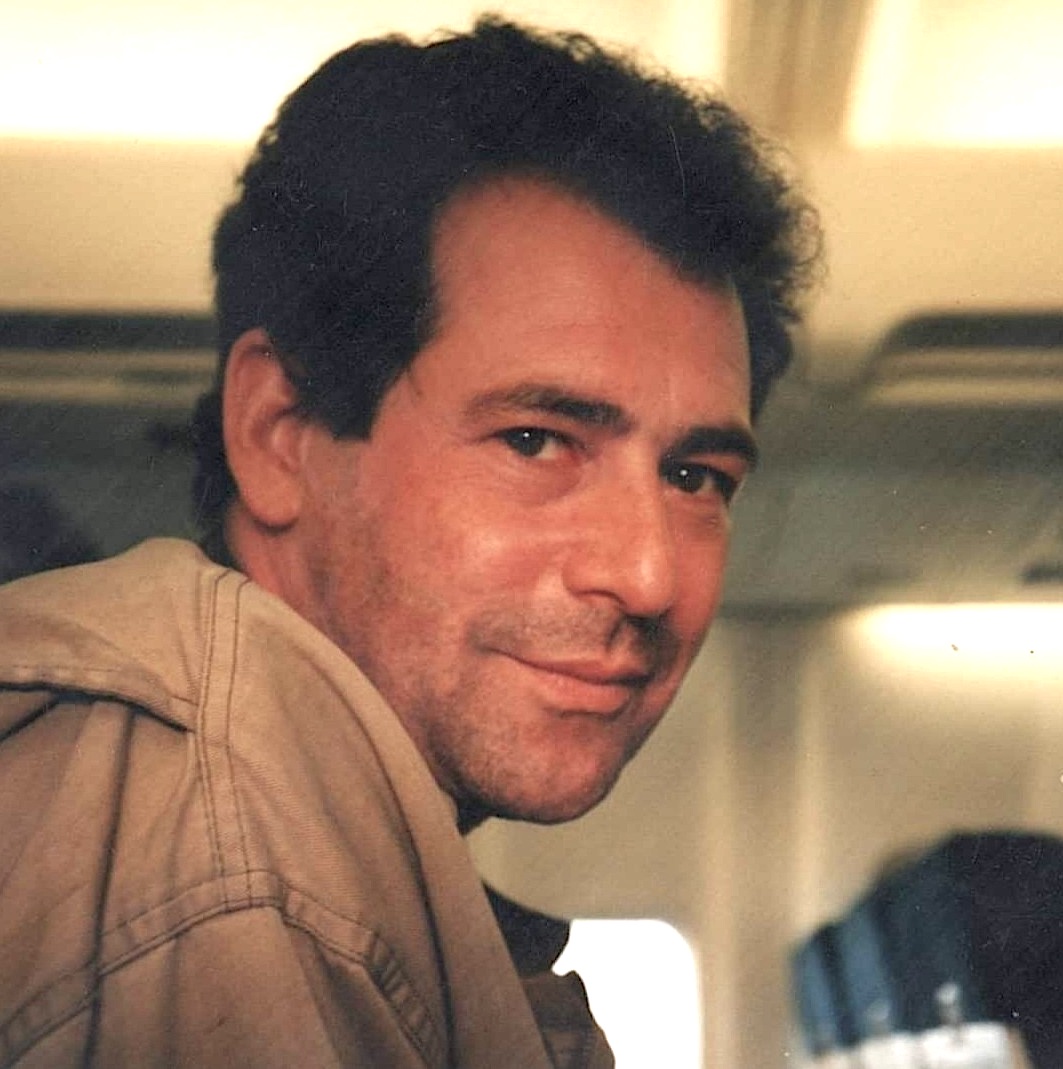

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Leonard Abrams, the publisher and editor of the East Village Eye, died on April 1 in New Jersey. He was 68.

His girlfriend, Angela Sloan, and godson, Thomas “Mas” Walker, both said Abrams had been driving back to New York City from one of his regular trips selling religious goods to botanica stores, when he pulled off to the side of the road and suffered a fatal heart attack.

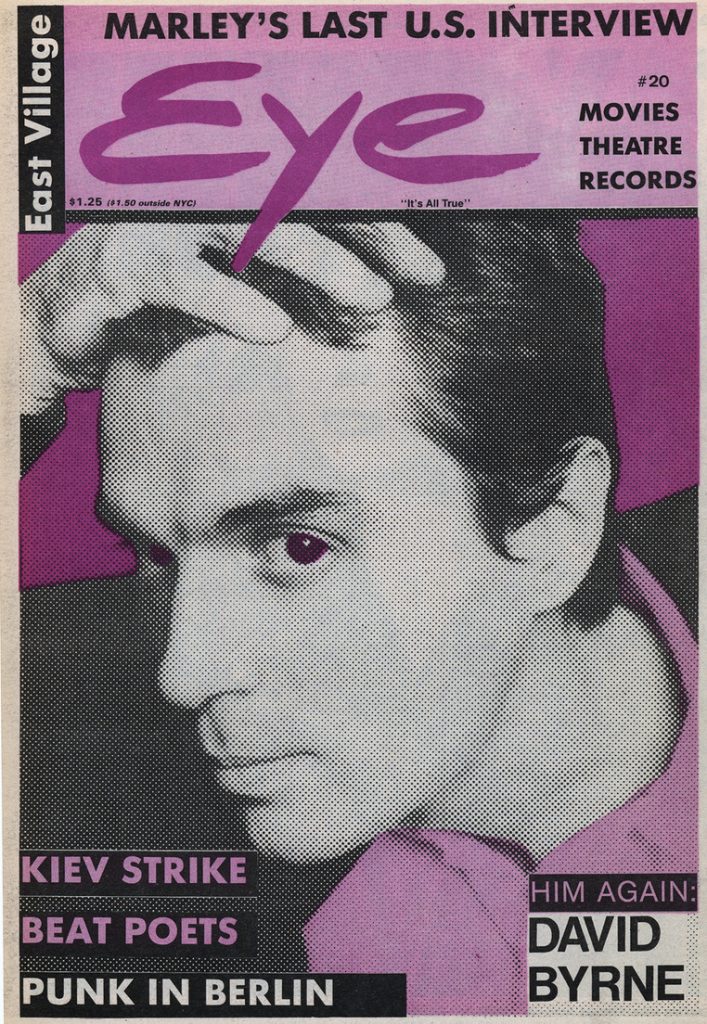

Abrams had been riding a personal high since the end of last year when the New York Public Library agreed to accept the archive of the East Village Eye, his 1980s Downtown culture magazine. Finding a proper home for the physical, pre-Internet publication had been a consuming, decades-long quest. The Eye’s archive has also been digitized and is available online.

Of course, there naturally had to be a party with friends and former Eye contributors and staff to celebrate the occasion, and one was duly held at the Bowery Electric on March 23.

“In my opinion, there is no better place than the New York Public Library [for the archive],” Abrams said, in his remarks during the fete, “the depth, the strength of the institution, their mission, that they’re for the people. This cannot possibly be a better outcome.”

No one imagined at that time that he would be gone less than two weeks later.

Leonard Abrams was born in Brooklyn and grew up in Spring Valley, N.Y., 35 miles north of the city. His father was a furrier and his mother worked for a bank.

He briefly attended Fordham University, then did stints in Denver and Boston before returning to New York. In 1979, at age 24, living in the midst of the East Village’s developing art scene, he founded the East Village Eye.

“He really did it on very little money,” Sloan said. “I think his mother gave him a little nest egg. He did it mainly by selling ads.”

Also helping make the start-up publication feasible, the city was more affordable back then.

“His first apartment was $165 a month, and he split it,” Sloan said. “He was a bike messenger when he was younger. He could make the rent in two days as a bike messenger. He drove a cab. He was a carny when he was 19, Upstate and in the South. He did everything.”

But printer’s ink was in his blood.

“He just always wanted to do a newspaper,” she said. “He even started a newspaper in high school. He wanted to start a community in print.”

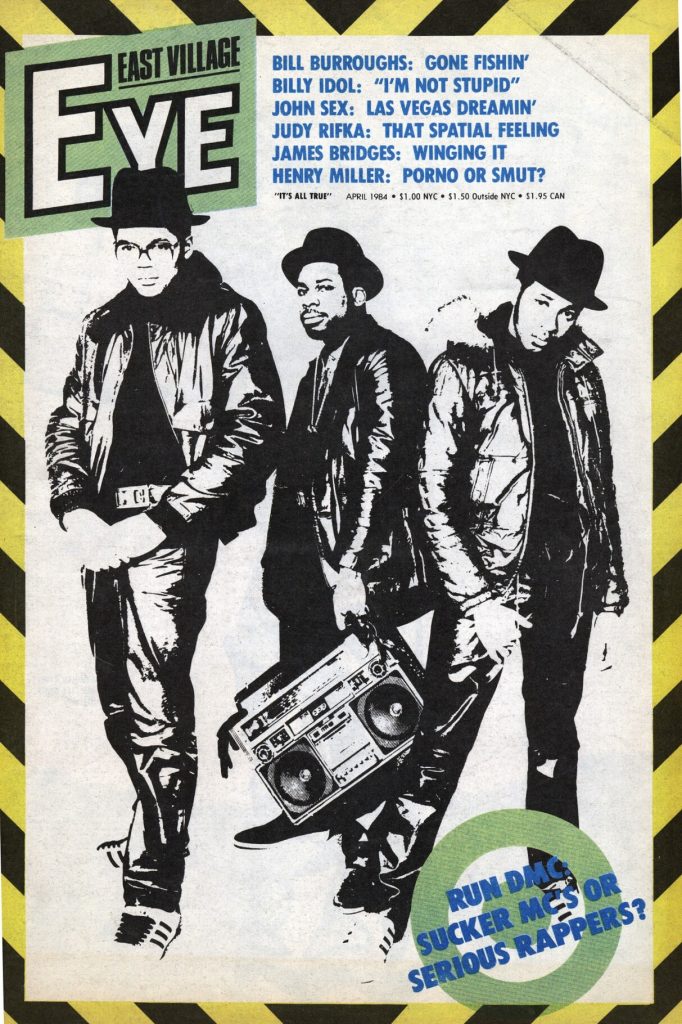

The Eye went on to publish 73 print issues — covering punk rock, painters, politics and more — until Abrams closed it in 1987.

“The Eye folded when I was too exhausted to continue and didn’t have anyone else to do what I was doing,” he told The Village Sun in February, while planning the Bowery Electric party.

Along with Kembra Pfahler and the Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, poet Bob Holman was one of the bash’s featured performers. The Eye published Holman’s poetry back when he was starting out in New York City.

“Just tragic,” Holman said. “There was no indication. … He was totally on that night. When I performed, he was standing at arm’s length from me. It was as if he was ingesting the poetry.”

(For a video of the party, click here.)

In addition to a publisher, Abrams was also a good event organizer and cultivator of social happenings.

“He did so much behind the scenes,” Holman reflected of Abrams’s career. “He was a great producer. He was a regular at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe and held events at Steve Cannon’s Tribes. He was a behind-the-scenes guy. You’d say he’d pull the strings — but he just let people be themselves. He was the ringmaster of the true outsiders.

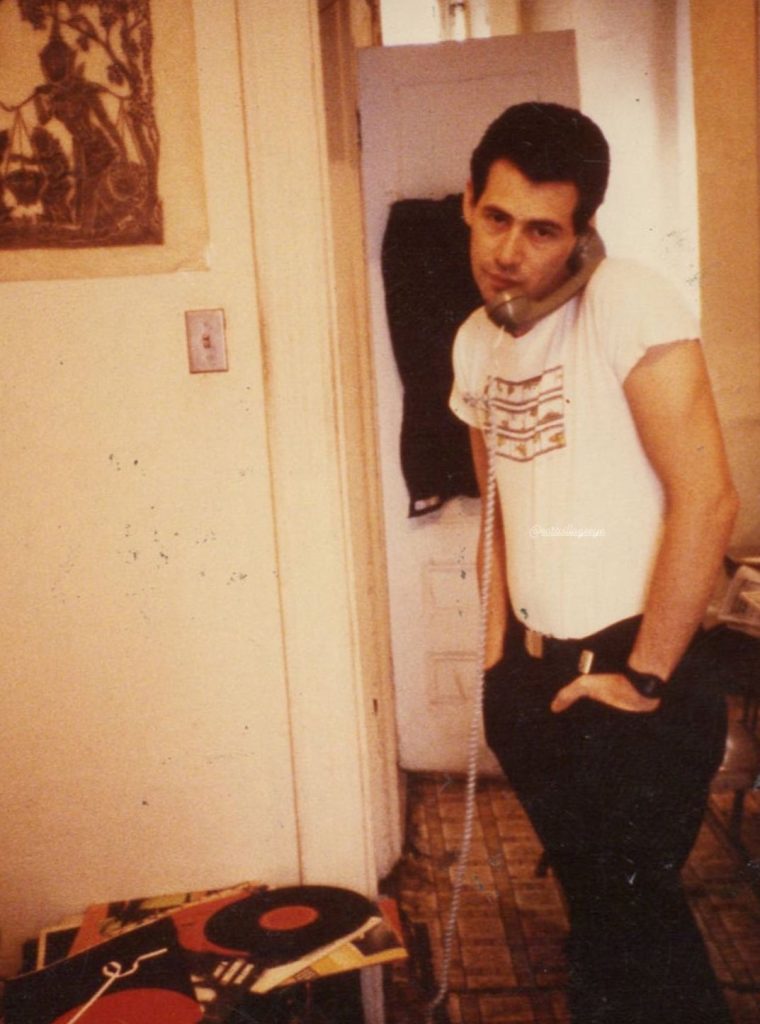

“He had one of those, like, open-to-everybody apartments,” Holman recalled. “It was the second floor of First Avenue and Second Street. Huge loft, before there were huge lofts. It was a hang spot, you know. He was a ringleader of the time.

“What a great man. What a great loss. It’s amazing how he got the major institution to appreciate the worth of what he did — and then to say goodbye to us all. I don’t know what to say — what an exit.”

Sloan said Abrams had been on a three-day trip, hitting botanicas in New Jersey, Baltimore, Philadelphia and northern Virginia. The religious items he hawked — including amulets, talismans, pyramids, Buddhas, lucky soap and the like — were from Mexico, Brazil and Colombia. He’d been at it for 20 years.

“Leonard was an artist who had to make a living,” she said. “He liked his customers a lot.”

As for the East Village Eye, it wasn’t much of a moneymaker.

“He made enough money to live, but he never had a lot,” Sloan said. “He was successful later on [after the Eye]… . But Leonard didn’t care about money.”

Toward the end, though, everything — not just the Eye archive success — was clicking for him.

“He had just placed the archive,” she said. “He was writing a lot more. He was planning a documentary about the botanicas. The party at the Bowery Electric sold out — it was a huge success. He was happy. If he had to go, I’m glad he went on a high note, and he did.”

Abrams previously made a documentary, “Quilombo Country,” in 2006, narrated by Chuck D. of Public Enemy, about Brazilian rural communities that were founded by runaway slaves.

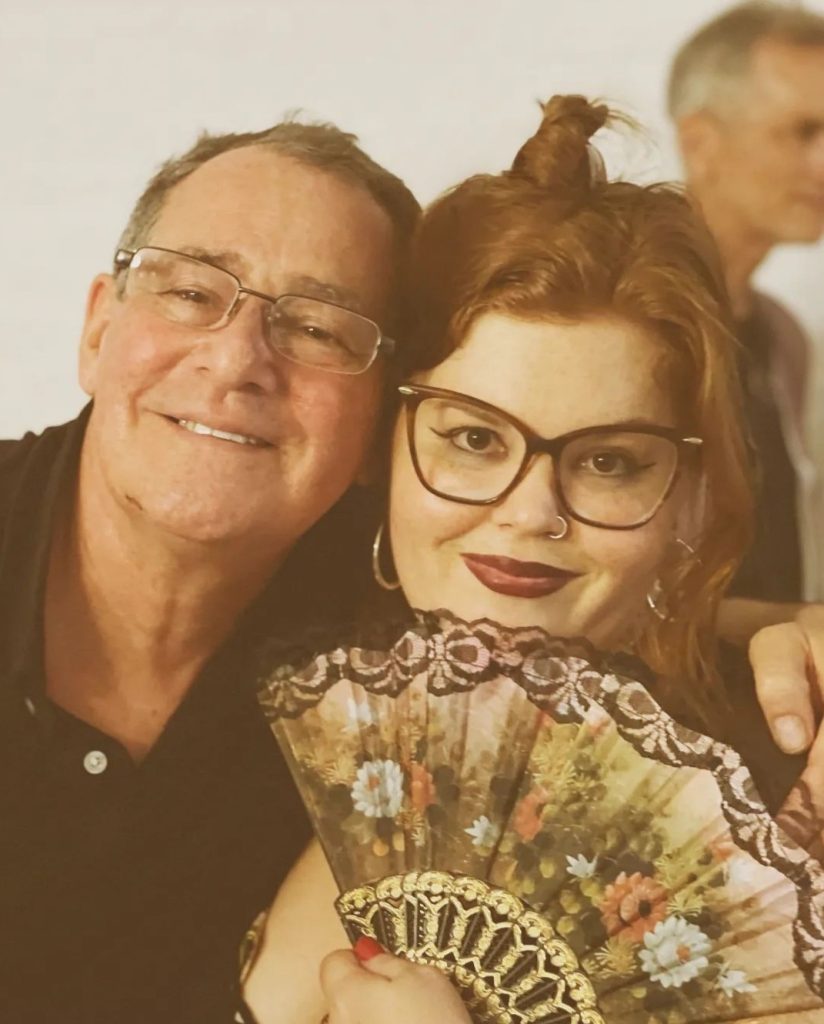

Sloan noted that Abrams had open-heart surgery in 2014 but appeared to have fully recovered. He lived with her at her place in Woodside, Queens. The two met in 2013 at the Bowery Poetry Club. She’s a poet and short-fiction writer. Abrams was older but it was never an issue, she said. Last year, he published a chapbook of her poetry called “Stories About Love.” They celebrated it with a party and readings at The Space cocktail bar, at 703 E. Sixth St.

Mitch Corber, a poet and videographer who worked at the East Village Eye, and Mas Walker put together a video of the recent Bowery Electric party. He recalled how Abrams operated the hip monthly on a shoestring, which naturally led to some grumbling.

“He was good at getting people to volunteer, I guess,” he said of Abrams. “And the writers felt neglected. He was paying the people, I don’t know, the printers, the truck drivers.”

Helping Abrams run the Eye was Celeste-Monique Lindsay, a friend since high school who now lives in Puerto Rico.

While at the Eye, Abrams was also close to Sybil Walker, who did interviews of the likes of writer Kathy Acker and actor Cookie Mueller. After she became ill, Abrams became the legal guardian of her son, Mas, who was then 13, and moved in with him in the East Village. The two lived together for years, with some occasional falling-outs during which Abrams would move out.

Although he wasn’t around during Abrams’s magazine career, Walker, who is now in his 30s, said he personally admired Abrams’s pioneering support of hip-hop and rap through the Hotel Amazon party that Abrams hosted at Downtown venues like ABC No Rio and the Mudd Club.

“He gave Public Enemy their start at the club, Hotel Amazon,” he said. “He brought in Queen Latifah, A Tribe Called Quest, KRS-One. They were the first magazine to print the word ‘hip-hop,'” he added of the Eye.

According to The New York Times, in a 1982 interview with the rapper Afrika Bambaattaa, the Eye defined “hip-hop” as an emerging subculture that included rapping, street fashion, graffiti and break-dancing.

Walker also recalled Abrams hosting colorful Thanksgiving parties with guests like Steve Cannon, Bob Holman and writer/art critic Anthony Haden-Guest. Abrams would have one beer and maybe a single puff of pot, but that was basically it, he kept his mind clear, he said.

Another thing about him, he said, “He always wore black.”

Walker accompanied Abrams on some of his visits to botanicas.

“These were like people that could put hexes on you,” he said. “He spoke the merchant’s talk. He spoke broken Spanish. You could feel heavy vibes when you went to these places. People would have tabs with him and he’d have to haggle with them.”

Over the years, Abrams bounced around, living in various places in the city. At one point, Walker said, Abrams was both working and living in a storefront in Ridgewood, Queens.

“Wherever he laid his hat was his home,” he said.

He noted that Abrams, in addition to previous heart surgery, had also beaten cancer.

Walker said he and the Eye founder had recently been patching things up, and shared a heartfelt embrace at the Bowery Electric party.

“It was just really upsetting because I felt we were turning over a new chapter,” he said. “I’m glad I got to see him that last time. It was a real powerful hug — let bygones be bygones.

“The East Village Eye going to the New York Public Library — it’s like going to heaven,” he reflected. “It’s just like the old days. Somebody said, ‘He went out on top.'”

Sante Scardillo, a Little Italy artist and activist, was a friend of Abrams and attended some of those epic Thanksgiving parties.

“‘It’s All True’ — with quotation marks — it was the editorial motto, always at the top of the front cover [in small print] of the East Village Eye, and it could have been for Leonard’s life, as well,” he said. “And that’s the way Leonard lived his life: It’s all true, a thousand times over. He had a great thirst for life.

“We were friends since we met over 35 years ago in the Cable Building [where the Eye’s office was located], which at the time still had in its airy lightwells the enormous flywheels that had powered the San Francisco-style cable cars coursing through Broadway. Years later, he told me that the only way to make a small fortune in publishing is to start with a large fortune. It’s probably not his original construct, but I heard it from him the first time ever. And he did not wind up with a small fortune.

“The East Village Eye in the ’80s was the equivalent of the Village Voice of previous decades, with smatterings of Paris Review and Artforum thrown in, and The New York Post mixed in and shaken. It was unique, and it was Leonard’s creation that left the deepest imprint in the culture, and what denizens and future generations will remember him for.”

Leonard Abrams is survived by a brother and two sisters, an aunt, nieces, a nephew, his godson, Mas Walker, and his girlfriend, Angela Sloan.

Around 200 people attended his funeral service at Plaza Jewish Community Chapel, at 91st Street and Amsterdam Avenue, and more watched it on Zoom. Burial was at Beth Moses Cemetery in Farmingdale, Long Island.

Great profile, what a life chronicling this city’s most soulful. ‘It’s All True’ — will be stealing that for a masthead, soonest.